(updated 10/26/18, 7/18/19,11/22/22 and 1/10/25)

Brian Chen’s recent piece about social media privacy in the NY Times inspired me to look more closely at the information that the major social networks have collected on me. Be warned: once you start down this rabbit hole, you can’t unlearn what you find. Chen says it is like opening Pandora’s box. I think it is more like trying to look at yourself from the outside in. There is a lot of practical information and tips here, you might want to file this edition of Web Informant away for future reference when you have the time to absorb all of it.

TL;DR: If you are short on time, F-Secure has this website where you can gather this data from the leading social networks quickly. But you still might want to ready about my experiences below.

Why bother? For one thing, the exercise is interesting, and will give you insights into how you use social media and whether you should change what and how you post on these networks in the future. It also shows you how advertisers leverage your account – after all, they are the ones paying the bills (to the news of some US Senators). And if you are concerned about your privacy or want to leave one or more of these networks, it is a good idea to understand what they already know about you before you begin a scrub session to limit the access of your personal information to the social network and its connected apps. Also, if you are thinking about leaving or migrating to another non-Twitter service, it would be nice to have a record of your contacts before you pull the plug. One other warning: these archives are only available for a limited time period, so BOLO for the emails telling you when you can download them, otherwise the links will expire and you will have to issue another request.

None of the networks make obtaining this information simple, and that is probably on purpose. I have provided links to the starting points in the process, but you first will want to login to each network before navigating to these pages. In all cases, you initiate the request, which will take hours to days before each network replies with an email that either contains a download link or an attached file with the information.

The results range from scary to annoyingly detailed and almost unreadable. And after you get all this data, there are additional activities that you will probably want to do to either clean up your account or tighten your privacy and security. Hang on, and good luck with your own journey down the road to better social network transparency about your privacy.

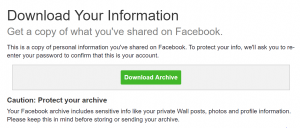

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dyi?x=AdkA0Kau6MLj_7I0

Facebook sends you an HTML collection of various items, some useful and some not. You download a ZIP archive. There is a summary of your profile, a collection of your posts to your timeline, a list of all of your friends (including those who have left Facebook) and when you connected with them, and any videos and photos that you have posted. Two items that are worth more inspection are a list of advertisers that have your information: I noticed quite a few entries to more than a dozen different state chapters of Americans for Prosperity PACs that are funded by the Koch brothers. Finally, there is a list of your phone’s contacts that it grabbed if you ran its Messenger application, which it justifiably has been getting a lot of heat for doing. Note that this is different from your friend list. Also, when I requested the archive Facebook temporarily locked my account which I then had to unlock before the download.

(The Verge has very detailed step-by-steo instructions that they try to keep current on the deletion process.)

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/psettings/member-data

LinkedIn sends you two ZIP collections of CSV files that you can open in separate spreadsheets that contain different lists. The first set includes connections, contacts, messages that you have exchanged with other LinkedIn members, and profile information, and the second has activity, account history and invites Most of the files contained just a single line of data, which made looking at all of them tedious. The two collections of files is a bit odd: you should ignore the first one (which you get almost immediately) and wait for the “final” archive, which is more complete and arrives several hours later. Most of this data is rather matter-of-fact. One file contains a summary of your profile that is used for ad targeting, but there is no list of advertisers like with the other networks. Another file contains the IP addresses and dates of your last 50 logins, and another contains the dates and names of people that you have searched for on the network. What bothered me the most about my list of LinkedIn connections was the number of them differed by two percent from what is displayed on my LinkedIn home page and in the spreadsheet itself. Why the difference? I have no idea.

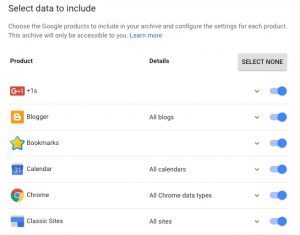

Google: Takeout.google.com

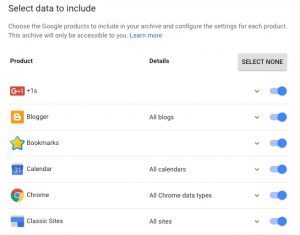

Google operates somewhat differently and more opaquely than the others mentioned here. First, you go to the link above, which is a separate service that will collect your Google archive. The screen shot shows you just some of the dozens of different Google services that you can select to use in the gathering process. In my experiment this process took the longest: more than three days, whereas the others took minutes to several hours. Even before you get your archive, scanning this list and selecting which services you want included in your report is a depressingly lengthy activity. When I finally got my archive, it spanned three ZIP files and more than 17GB in total, which is more than all the others combined.

Google operates somewhat differently and more opaquely than the others mentioned here. First, you go to the link above, which is a separate service that will collect your Google archive. The screen shot shows you just some of the dozens of different Google services that you can select to use in the gathering process. In my experiment this process took the longest: more than three days, whereas the others took minutes to several hours. Even before you get your archive, scanning this list and selecting which services you want included in your report is a depressingly lengthy activity. When I finally got my archive, it spanned three ZIP files and more than 17GB in total, which is more than all the others combined.

However, that is just the beginning. When you bring up a web page that shows the various Google services, you have to separately extract the data for each service individually and each service uses it own data format that you then need to view in a particular application: for example, your calendar items are in iCal format, your email data is in MBOX format, and others are extracted in JSON format. Analyzing all this information can probably take a data scientist the better part of a few days, let alone you and I, who don’t have the tools, dedication or time. If you are thinking of de-Googling your life, you will have to do more than just switch to an iPhone and give up Gmail.

But wait, there is more: emails that you delete or find their way into your Spam folder are still part of your archive. In the Googleplex, everything is accounted for. Note that if you have uploaded any music to Google Play Music, this data isn’t part of your archive and you’ll have to download that separately.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/settings/account

Twitter will send you two files: one that is a PDF attachment that contains a list of all the advertisers that have your information, but the advertisers’ names are shown in their Twitter IDs and thus not very meaningful. The second document is an Html collection of all your tweets, and you can bring up your browser or access the data via in two formats: JSON and CSV exports by month and year. Notice that there is nothing mentioned about downloading all of your Twitter followers: you will have to use a third-party service to do this. One thing I give Twitter props for is that you have a very clear series of settings menus that might be useful to study and change as well, including connected apps and privacy settings. Facebook and LinkedIn constantly are rearranging these menus and make changes to their structure and importance, which makes them more difficult to find when you are concerned about them. But Twitter at least give you more control over your privacy settings and tries to make it more transparent.

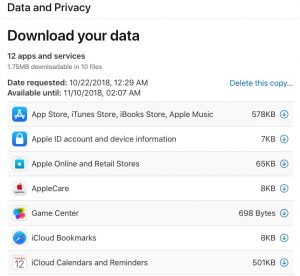

Apple: http://privacy.apple.com/

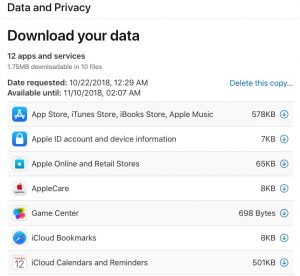

Apple opened up its privacy portal earlier this summer to a few geographies and then to US and other countries in the fall. It took a day to request my data from 12 different datasets that it maintains, as you can see in the screenshot here. Each database corresponds to a particular app, such as AppleCare requests, iCloud bookmarks, interactions with your AppleID account, and contacts. You get .ZIP files for each one (split into smaller segments, if you request that), and you have to individually download each one. The link to the downloads expires in two weeks, which is a nice touch.

Apple opened up its privacy portal earlier this summer to a few geographies and then to US and other countries in the fall. It took a day to request my data from 12 different datasets that it maintains, as you can see in the screenshot here. Each database corresponds to a particular app, such as AppleCare requests, iCloud bookmarks, interactions with your AppleID account, and contacts. You get .ZIP files for each one (split into smaller segments, if you request that), and you have to individually download each one. The link to the downloads expires in two weeks, which is a nice touch.

Manipulating these files isn’t easy. Almost each of these 12 files contain one or more nested .ZIP files within them, and it feels at time you are chasing your data down a hall of mirrors. My total downloaded, when everything was unzipped, was 7GB and covered more than 170 different files. Everything unzips into mostly .CSV files that will require parsing in your favorite spreadsheet. A lot of the information is coded in such a way that it meaningless without a lot of further study to tie back to your activities. For example, my Apple ID sign in file has a list of login dates for different services. Because it comes in an CSV import, you have to ensure that you format the date fields properly. In other words, getting this data is easy. Getting any actionable or useful information from the trove is not.

One data collection is useful, and that is your contacts that is in either iCloud or in your Apple address book. You will get individual vCards for each person, which could be useful in case of a disaster. There is also a list of all the phone calls made on your iPhone (if you have one), and again, parsing that into a spreadsheet will be some effort. That can be found in the “Other data/Apple Features using iCloud/Call history bucket. Think of this exercise as a treasure hunt. Like some of the other vendors’ data dumps, there is a CSV collection of advertisers, under marketing communications, along with the date and time they were delivered to your endpoint device. There are copies of anything you have purchased at an Apple store, which is also useful, if you can find them buried deep within in the Apple Online and Retail Store folder.

Action items

So what should you do? First, delete the Facebook Messenger phone app right away, unless you really can’t live without it. You contacts are still preserved by Facebook, but at least going forward you won’t have them snooping over your shoulder. You can still send messages in the Web app, which should be sufficient for your communications.

Second, start your pruning sessions. As I hinted in the Twitter entry above, you should examine the privacy-related settings along with the connected apps that you have selected on each of the four networks. The privacy settings are confusing and opaque to begin with, so take some time to study what you have selected. The connected apps is where Facebook got into trouble (see Cambridge Analytica) earlier this month, so make sure you delete the apps that you no longer use. I usually do this annually, since I test a lot of apps and then forget about them, so it is nice to keep their number as small as possible. In my case, I turned off the Facebook platform entirely, so I lost all of these apps. But I figured that was better than their hollow promises and apologies. Your feelings may be similar.

Third, protect your collected data. Don’t leave this data that you get from the social networks on any computer that is either mobile or online (which means just about every computer nowadays). I would recommend copying it to a CD (or in Google’s case, several DVDs) and then deleting it from your hard drive. Call me paranoid, or careful. There is a lot of information that could be used to compromise your identity if this gets into the wrong hands.

Finally, think carefully about what information you give up when you sign up for a new social network. There is no point in leaving Facebook (or anyone else) if you are going to start anew and have the same problems with someone else down the road. In my case, I never gave any network my proper birthday – that seems now like a good move, although probably anyone could figure it out with a few careful searches.

Some friends of mine have 23 connected devices to their home network: a Nest thermostat, security cameras, Alexa, smart TVs, network printers, gaming systems, smart watches and their computers. I am sure I have forgotten a few others. All of them can be exploited and used for evil purposes. Think of them as that back door to your home that is wide open.

Some friends of mine have 23 connected devices to their home network: a Nest thermostat, security cameras, Alexa, smart TVs, network printers, gaming systems, smart watches and their computers. I am sure I have forgotten a few others. All of them can be exploited and used for evil purposes. Think of them as that back door to your home that is wide open.

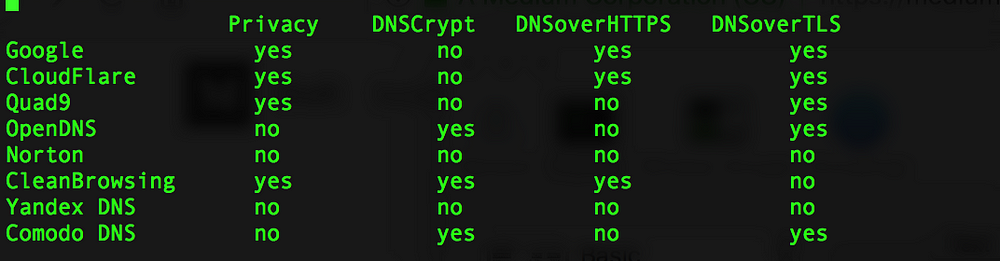

Back when I wrote that article, there was a growing need for providing better DNS services that were more secure and more private than the default one that comes with your broadband provider. But one of the great things about the Internet is that you usually have lots of choices for something that you are trying to do. Don’t like your hosting provider? Nowadays there are hundreds. Want to find a better server for some particular task? Now everything is in the cloud, and you have your choice of clouds. And so forth.

Back when I wrote that article, there was a growing need for providing better DNS services that were more secure and more private than the default one that comes with your broadband provider. But one of the great things about the Internet is that you usually have lots of choices for something that you are trying to do. Don’t like your hosting provider? Nowadays there are hundreds. Want to find a better server for some particular task? Now everything is in the cloud, and you have your choice of clouds. And so forth. As I mentioned earlier, he did a very thorough job testing the DNS providers from around the globe, using VPNs to connect to their service from 17 different locations. He found that all of the providers performed well across North America and Europe, but elsewhere in the world there were differences. Overall though,

As I mentioned earlier, he did a very thorough job testing the DNS providers from around the globe, using VPNs to connect to their service from 17 different locations. He found that all of the providers performed well across North America and Europe, but elsewhere in the world there were differences. Overall though,

and demonstrated conic sections, such as the intersection of a plane and a cone. Back then, we didn’t have Mathematica or color textbooks to show engineering students how to draw these things. These models were constructed out of strings threaded through moveable brass pieces that were attached to wooden bases, using lead weights to keep the strings taut.

and demonstrated conic sections, such as the intersection of a plane and a cone. Back then, we didn’t have Mathematica or color textbooks to show engineering students how to draw these things. These models were constructed out of strings threaded through moveable brass pieces that were attached to wooden bases, using lead weights to keep the strings taut. Crocker was in Houston for two weeks, starting two weeks after the hurricane hit. He has been a shelter supervisor at both small and large operations, a dispatcher for daily, local disasters, and helps out in other situations, both in the field and in their offices. Given his tenure as a volunteer, he has taken numerous Red Cross training classes, including learning to drive a fork lift (although not that well, he ruefully notes).

Crocker was in Houston for two weeks, starting two weeks after the hurricane hit. He has been a shelter supervisor at both small and large operations, a dispatcher for daily, local disasters, and helps out in other situations, both in the field and in their offices. Given his tenure as a volunteer, he has taken numerous Red Cross training classes, including learning to drive a fork lift (although not that well, he ruefully notes).

Minitel? That French videotext terminal thing from the 1980s and 1990s? Didn’t that die an ignominious death from the Internet? Yes, that is all true. But for its day, it was ahead of its time and ahead of today’s Internet in some aspects too. You’ll see what I mean when you consider its content and micropayments, network infrastructure, and its hybrid public/private ownership model. Let’s dive in.

Minitel? That French videotext terminal thing from the 1980s and 1990s? Didn’t that die an ignominious death from the Internet? Yes, that is all true. But for its day, it was ahead of its time and ahead of today’s Internet in some aspects too. You’ll see what I mean when you consider its content and micropayments, network infrastructure, and its hybrid public/private ownership model. Let’s dive in. The use of technology in schools is analyzed from the actual front lines of a ninth grade classroom in South Central LA in

The use of technology in schools is analyzed from the actual front lines of a ninth grade classroom in South Central LA in Alicia Eler once worked for me as a reporter, so count me as a big fan of her writing. Her first book, called

Alicia Eler once worked for me as a reporter, so count me as a big fan of her writing. Her first book, called