All this talk about Occupy Greenland this week got me reading this 2013 report from the US Naval Institute about the harsh realities about shipping goods across the Arctic seas. The TL;DR: shipping loads of containers across the top of the world, while shorter in distance than sending it through Panama and Suez — isn’t necessarily cheaper when you do the basic math. Here is why:

First off, the problem is that the typical container ships are huge, and they come that way for a simple reason: the more they carry, the cheaper the cost per container to send it from one port to another. The smaller container ships that could be run in the Arctic are because the ice breakers aren’t as wide. There are also shallower channels that restrict the size of these ships when compared to the global routes. When you add all these factors up, a container going through the Arctic will cost more than twice as much as sending it “the long way around.”

Second, the Arctic isn’t ice-free year round. In actuality, even with global warming, routes are ice-free for only a third of the year, and sometimes less. On top of this, weather conditions can change quickly. Global shipping depends on tight schedules. These also involve making several stops along the way to supply just-in-time manufacturing systems, and spreading the costs of shipping across the route. A typical 40-some-day trip from the eastern US to Asia route is shared by a series of six ships making regular stops. This is called the network effect. Going across the Arctic would not have as many intermediate stops.

But what about other kinds of shipping, such as minerals or energy products that come from Arctic sources? It is possible, but still depends on all sorts of infrastructure to extract and load this material — which does not exist and probably won’t for quite some time.

Finally, with or without Greenland, to send stuff across the Arctic isn’t the same as crossing the Pacific or Atlantic oceans because the connectivity is poor. A typical route has to transit a series of narrow straits that is currently claimed by Russia, with high fees to move through these straits.

“Arctic routes do not now offer an attractive alternative to the more traditional maritime avenues, and are highly unlikely to do so in the future,” the report concludes. And while things have changed somewhat since this report was written, the factors cited above are still valid.

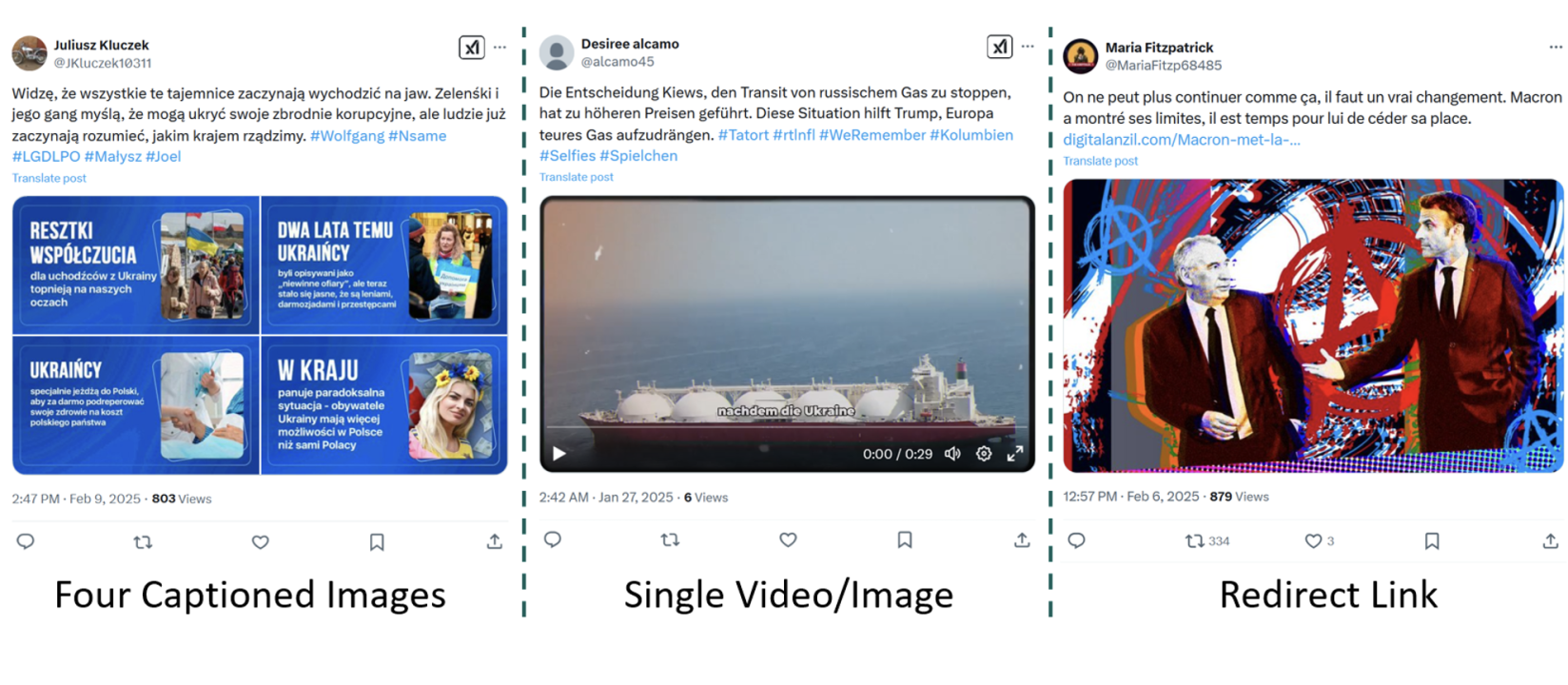

You might still be using Twitter, for all I know, and are about to witness yet another trolling of the service by turning all user blocks into mutes, which is Yet Another Reason I (continue to) steer clear of the thing. That, and its troller-in-chief. So now is a good time to review your social strategy and make sure all your content creators or social managers are up on the latest research.

You might still be using Twitter, for all I know, and are about to witness yet another trolling of the service by turning all user blocks into mutes, which is Yet Another Reason I (continue to) steer clear of the thing. That, and its troller-in-chief. So now is a good time to review your social strategy and make sure all your content creators or social managers are up on the latest research. ot to witness a real-time deepfake audio generator. It needed just a sample of a few seconds of my voice, and then I was having a conversation with a synthetic replica of myself. Eerie and creepy, to be sure.

ot to witness a real-time deepfake audio generator. It needed just a sample of a few seconds of my voice, and then I was having a conversation with a synthetic replica of myself. Eerie and creepy, to be sure.