Among the confusion over whether the US government is actively working to prevent Russian cyberthreats comes a new present from the folks that brought you the Doppelganger attacks of last year. There are at least two criminal gangs involved, Struktura and Social Design Agency. As you might guess, these have Russian state-sponsored origins. Sadly, they are back in business, after being brought down by the US DoJ last year, back when we were more clear-headed about stopping Russian cybercriminals.

Doppelganger got its name because the attack combines a collection of tools to fool visitors into thinking they are browsing the legit website when they are looking at a malware-laced trap. These tools include cybersquatting domain names (names that are close replicas of the real websites) and using various cloaking services to post on discussion boards along with bot-net driven social media profiles, AI-generated videos and paid banner ads to amplify their content and reach. The targets are news-oriented sites and the goal is to gain your trust and steal your money and identity. A side bonus is that they spread a variety of pro-Russian misinformation along the way.

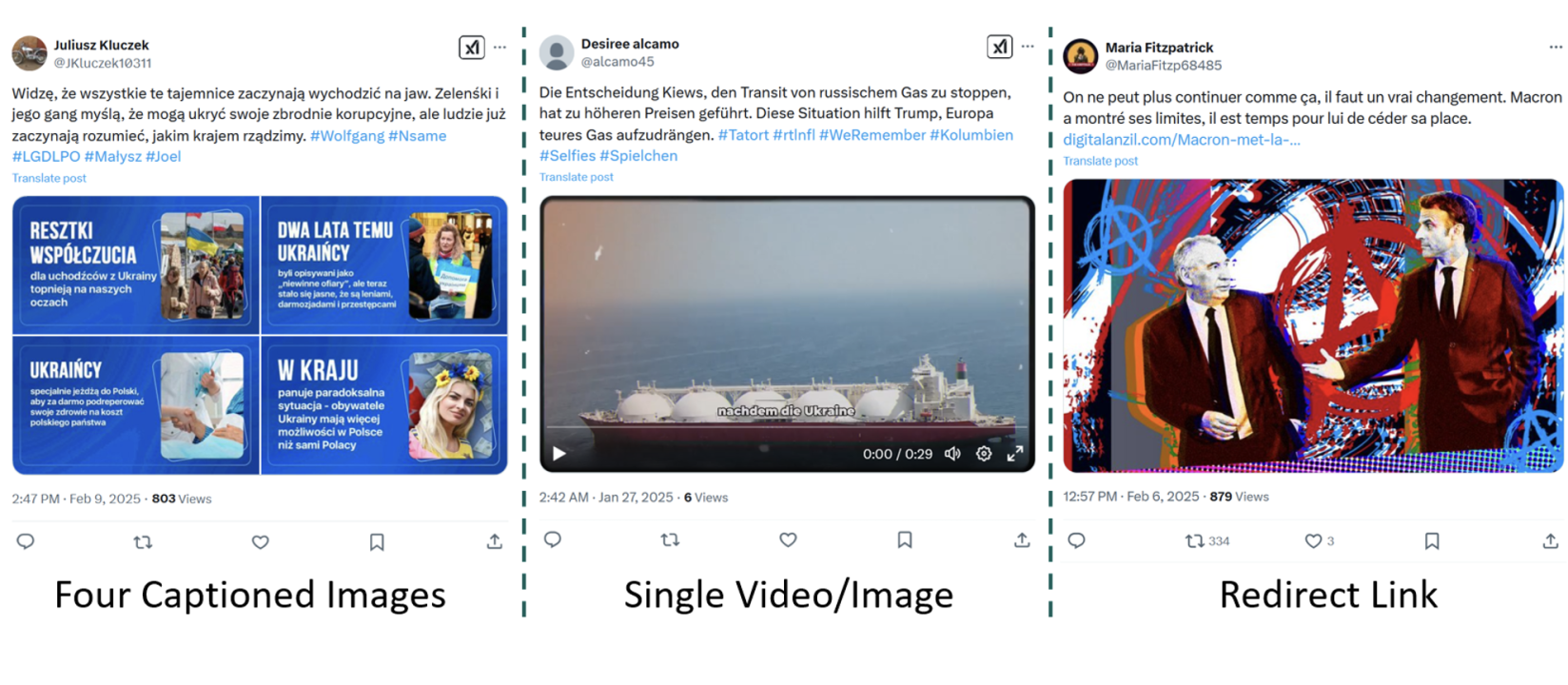

Despite the fall 2024 takedowns, the group is once again active, this time after hiring a bunch of foreign speakers in several languages, including French, German, Polish, and Hebrew. DFRLab has this report about these activities.They show a screencap of a typical post, which often have four images with captions as their page style:

These pages are quickly generated. The researchers found sites with hundreds of them created within a few minutes, along with appending popular hashtags to amplify their reach. They found millions of views across various TikTok accounts, for example. “During our sampling period, we documented 9,184 [Twitter] accounts that posted 10,066 of these posts. Many of these accounts were banned soon after they began posting, but the campaign consistently replaces them with new accounts.” Therein lies the challenge: this group is very good at keeping up with the blockers.

The EU has been tracking Doppleganger but hasn’t yet updated its otherwise excellent page here with these latest multi-lingual developments.

The Doppelganger group’s fraud pattern is a bit different from other misinformation campaigns that I have written about previously, such as fake hyperlocal news sites that are primarily aimed at ad click fraud. My 2020 column for Avast has tips on how you can spot these fakers. And remember back in the day when Facebook actually cared about “inauthentic behavior”? One of Meta’s reports found these campaigns linked to Wagner group, Russia’s no-longer favorite mercenaries.

It seems so quaint viewed in today’s light, where the job of content moderator — and apparently government cyber defenders — have gone the way of the digital dustbin.

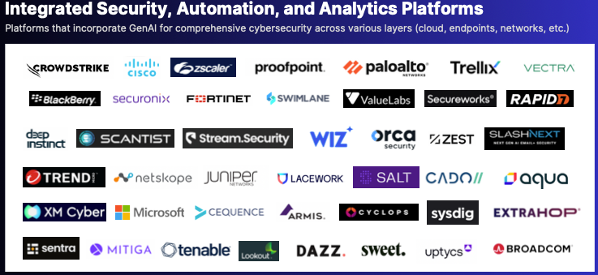

The class of products called SOAR, for Security Orchestration, Automation and Response, has undergone a major transformation in the past few years. Features in each of the four words in its description that were once exclusive to SOAR have bled into other tools. For example, responses can be found now in endpoint detection and response tools. Orchestration is now a joint effort with

The class of products called SOAR, for Security Orchestration, Automation and Response, has undergone a major transformation in the past few years. Features in each of the four words in its description that were once exclusive to SOAR have bled into other tools. For example, responses can be found now in endpoint detection and response tools. Orchestration is now a joint effort with