This is the story about how a group of very dedicated people came together at the dawn of the Internet era to build something special, something unique and memorable. It was eventually known as the Interop Shownet, and it was created in September 1988 at the third Interoperability conference held in Santa Clara, California. This is the story of its evolution, and specifically how its show network became a powerful tool that moved the internet from a mostly government-sponsored research project to a network that would support commercial businesses and be used by millions of ordinary people in their daily lives.

But before we dive into what happened then, we must turn back the clock a couple of years.

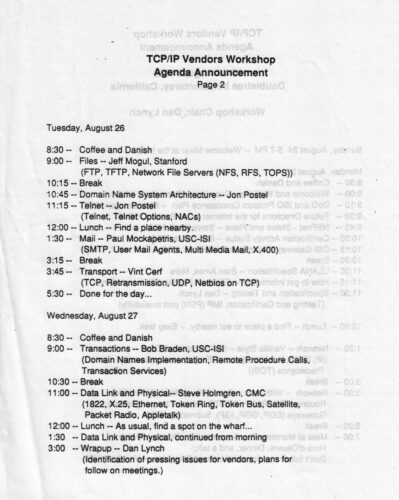

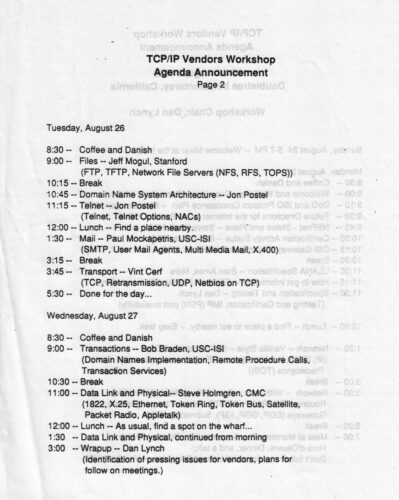

In August 1986, a few very motivated people got the bright idea to teach others how to implement the early internet protocols. This first conference, called the TCP/IP Vendors Workshop, was held in Monterey California and was by invitation only. (Agenda photocopy) Speakers included Vint Cerf (who was at MCI), Jon Postel (RFC Editor and at ARPANET before playing a key role in internet administration), and Paul Mockapetris and Bob Braden (both at USC-ISI).

In August 1986, a few very motivated people got the bright idea to teach others how to implement the early internet protocols. This first conference, called the TCP/IP Vendors Workshop, was held in Monterey California and was by invitation only. (Agenda photocopy) Speakers included Vint Cerf (who was at MCI), Jon Postel (RFC Editor and at ARPANET before playing a key role in internet administration), and Paul Mockapetris and Bob Braden (both at USC-ISI).

Two subsequent conferences were held the following March in Monterey and then December in Crystal City, Virginia, both were called the TCP/IP Interoperability Conference. All three were unusual events for several reasons: first, the presenters and instructors were the actual engineers that developed the earliest internet protocols. They were also there to impart knowledge, rather than sell products – mainly because few commercial products were yet invented.

By September of 1988, the format of the conference changed, and expanded beyond lectures to a more practical proving ground. The event was renamed once again, and so Interop – and its show network — was born. The mission was still to teach internet technologies and protocols, but for the first time the event was used to test and demonstrate various internet communications devices on an active computer network. That show used a variety of Ethernet cables to connect 51 exhibitors together, with T1 links to NASA Ames Research Center and NSFNet in Ann Arbor Michigan.

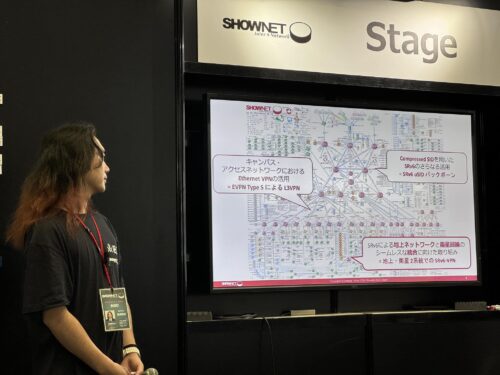

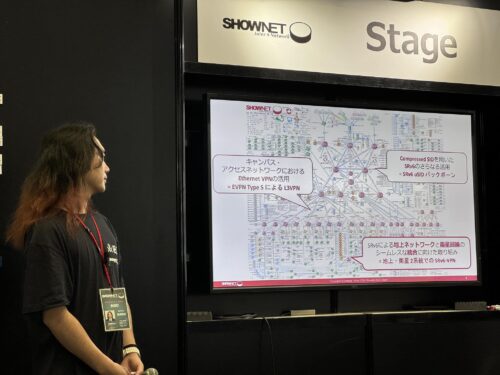

The network diagram of the 2024 Tokyo Shownet in all of its complexity

The Interop conference quickly grew into a worldwide series of events (1) with multiple shows held in different cities that were attended by tens of thousands of visitors with more than a thousand connected booths. In those early years, the largest shows were held in Tokyo, which began in 1994 and continued annually (with a pause because of the pandemic), with the latest show held this past summer. This year’s show spanned over 200 vendors’ booths and drew about 40,000 visitors each of its three days. The Tokyo Interop is also where the Shownet not only has survived, but thrived and continues to innovate and demonstrate internet interoperability to this very day. Many products had their world or Japanese debuts at various Tokyo Interops, including Cisco’s XDR and 8608 Router and NTT’s Open APN.

The name of Interop’s network also evolved over time. It was called variously the Show and Telnet, the Interop Net and eventually the Shownet, which is how we’ll refer to it in this article.

My own interop journey with Network Computing magazine

Before I get into the evolution of Interop and the role and history of its Shownet, I should first mention my own personal journey with Interop. If we jump back to 1990, I was in the process of creating the first issue of Network Computing magazine for CMP Media. Our first issue was going to debut at the Interop show, the second time it was held that fall in the San Jose Convention Center.

The publisher and I both thought this was the best place for our debut for several reasons. First, our magazine was designed for similar motivations — to demonstrate what worked in the new field of computer networking. We had designed our publication around a series of laboratories that had the same equipment found in a typical corporate office, including wide-area links, and a mixture of PC DOS, Macintoshes, Unix and even a DEC minicomputer connected together. Second, we wanted to make a big splash, and our salespeople were already showing prototype issues ahead of the show to entice advertisers to sign up. Finally, Network Computing’s booth would be connected to the Shownet and the greater internet, just like many of the exhibitors who were trying out some product for the very first time.

One other feature about Network Computing that set us apart from other business trade magazines at the time: each bylined article would contain the email address of the author, so that readers could contact them with questions and comments. I wanted to use the domain cmp.com and set up an actual internet presence, but alas I was overruled by management, so we ended up using a gateway maintained by one of the departments at UCLA where a couple of our editors were housed. While author’s email contacts are now common, it was a radical notion at the time.

The earliest days of Interop

The Interop show in the late 1980s was a markedly different trade show from others of its era. At the time, trade shows with networked booths were non-existent. By way of perspective, up until that point in those early years, there were two kinds of conferences: one that focused on the trade show with high-priced show floors and fancy exhibits. There, exhibitors were forced to “pay to play,” meaning if they bought booth space, they could secure a speaking slot at the associated conference. The other was a more staid affair that was a gathering of the engineers and actual implementers. Interop was a notable early example bridging the two: it looked like a trade show but was more of a conference, all in the guise of getting better commercial products out into the marketplace. It helped that it had its roots in those early TCP/IP conferences.

“You could see the internet in a room thanks to the Shownet, with hundreds of nodes talking to each other. That was unique for its time,” said Carl Malamud. “The Shownet was the most complex internet installation you could do at any moment of time.” Malamud would play several key roles in the development of various early internet-based projects, including running the first internet-based radio station, and was a Shownet volunteer in 1991.

That complexity has been true from the moment the Shownet was first conceived to the present day. Many of the internet’s protocols — both at in its earliest years and up to the present era — were debugged over the Shownet: volunteers recall testing Netbios over TCP/IP, 10BaseT ethernet, SNA over TCP/IP, FDDI, SNMP, IPv6, various versions of segment routing and numerous others. That extensive protocol catalog is a testament to the influence and effectiveness of the Shownet, and how enduring a concept it has been over the course of internet history. Steve Hultquist, who was part of the early NOC teams, remembers that the very first version of 3Com’s 100BaseT switch — with “serial number 1” — was installed on the ShowNet.

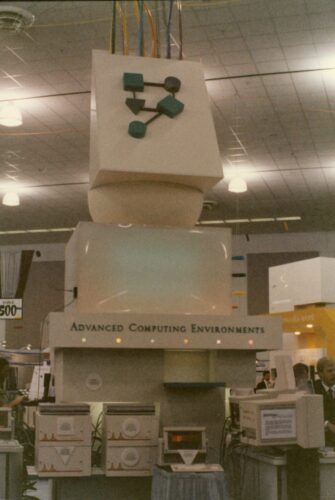

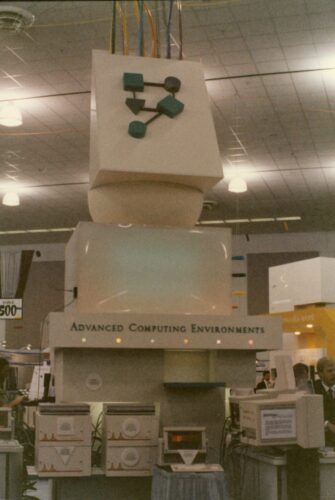

The organization behind Interop, Advanced Computing Environments, and their booth at the 1989 show

The force behind Interop was Dan Lynch, who passed away earlier this year. Lynch foresaw the commercial internet and designed Interop to hasten its adoption. He based Interop on a series of efforts to bring together TCP/IP vendors, and the proto-Interop shows that were run in the middle 1980s that were more “plugfests” or “Connectathons” where vendors would try out their products. The main difference was those efforts deployed mostly proprietary protocols, whereas Interop ran on open source.

He told Sharon Fisher in November 1987: “There are millions of PCs out there and they’re starting to get networked in meaningful ways, not just in little printer-sharing networks.” Part of his vision — and those that he recruited — was the notion of interoperability which could be used as a selling point and as an alternative to single-vendor proprietary networks from IBM, Digital Equipment Corporation and others that were common in that era. Larry Lang, who worked for many years at Cisco, said, “The reassurance that it was okay to give up having ‘one throat to choke’ came from confidence that the equipment was interoperable. It is hard to remember a time when that was a worry, but it sure was.”

Part of Lynch’s vision was ensuring that proving interoperability was a very simple litmus test: did the product being exhibited work as advertised in a real-world situation? That seems like common sense, but doing so in a trade show context was a relatively rare idea. And while it was a simple question, the answer was usually anything but simple, and sometimes the reasons why some product didn’t work — or didn’t work all the time — was what made the Shownet a powerful product improvement tool. That is just as true today as it was back then. The more realistic the Shownet, the more often it would expose these special circumstances that would bring out the bugs and other implementation problems.

It would prove to be a potent and enduring vision.

What does interoperability mean?

The notion of interoperability seems so common sense now — and indeed it is the default position for most of the current networking world. However, in the early days of the internet it was fraught with problems, both in terms of larger scale implementations and smaller issues that would prevent products from working reliably. One of Sharon Fisher’s articles in Computerworld in 1991 (2) speaks about TCP/IP this way: “The astounding thing is not how gracefully it performs but that it performs at all. TCP/IP is not for everyone.” Times certainly have changed in the 33 years since that was written. Today the notion of internet connectivity, using TCP/IP protocols, is a given assumption in any computing product, from smart watches to the largest mainframe computers.

Those early implementation differences plagued both large and small vendors alike, and required a meeting of the minds where the protocol specifications weren’t exacting enough to ensure its success, or where bugs took time to resolve. Enter the Interop conference. As a reminder, in those early days the popular IP applications were based on FTP, SMTP, and SNMP. The web was still being invented and far away from being the de facto smash hit that it is today. Video conferencing and streaming didn’t exist. Telephones still ran on non-IP networks.

One of the early casualties was the Open Systems Interconnect series of protocols. It was precisely because of the interoperability among TCP/IP products and “the failure of OSI to effectively demonstrate interoperability in the early 1990s that was the final nail in its coffin,” said Lloyd. There are other stories of the defeat of OSI, such as this one in the IEEE Spectrum. (3)

The relationship among the Shownet, the conference tutorials, and the NOC

To accomplish Lynch’s vision, Interop wasn’t just the Shownet, but its interaction with two other elements that became force multipliers in the quest for interoperability. These were the tutorials that were given preceding the opening of the show floor, and the Network Operations Center (NOC) team that ran the network itself. All three had an important synergy to promote the actual practice of interoperability among different vendors’ products: not just in the demonstration of what worked with what but proving out protocol mismatches or programming errors so that new equipment could be made to interoperate.

Dave Crocker, who authored many RFCs and served on the Interop program committee that selected speakers in the 1990s, called out this tripartite structure of Shownet, NOC and conference as a major strength of Interop. “Interop was able to contrast the technologies of the internet with the interoperability of non-internet technologies, such as IBM’s Systems Network Architecture. It had very pragmatic implications and wasn’t just promoting marketing speak.”

The tutorials (and by way of disclosure, I taught a few of them during those early years, as well as also serving with Crocker on the program committee) were given by many of the engineers who developed those early protocols and techniques and other pieces of internet technology, so that others could learn how to best implement them. Here is where Interop contained its secret sauce: the tutorials were given by the people that contributed to the underlying protocols and code, in some cases code so new it was changing over the duration of the show itself. “It was only after getting to Interop that we found out how few options were actually used by most implementations, and only then did we have access to the larger internet and various versions of Unix computers,” said Brian Lloyd, who worked at Telebit at the time. “It was real bleeding edge stuff back then and the place to go for product testing and see how marketers and engineers would work together.”

And the NOC was a real one, like what could be found at large corporations, monitoring the network for anomalies and used to debug various implementations leading up to the show’s opening moments. “It was unusual for its time,” said Fisher in another article in Infoworld. (4) “The NOC team was infamous in the trade press for its tours and the time members took to explain things to us,” she said. Malamud recalls that the NOC had a strict “no suits” policy, meaning that its denizens were engineers that rolled up their shelves and got stuff done.

All of this happened with very few paid staff: most of the people behind the Shownet and NOC were volunteers who came back, show after show, to work on setting things up and then taking them down after the show ended. That was, and to some extent still is, a very high-pressure environment: imagine wiring up a large convention center and connecting all of its conference rooms with a variety of network cabling.

One of the more infamous moments of Interop was the Internet Toaster, created by John Romkey (5) originally for the 1990 show. “I wanted to get people thinking of SNMP not just as getting variables, but for control applications, a wider vision. So we had an SNMP controlled toaster. If you put bread in the toaster, and set a variable in SNMP, the toaster would start toasting. There was a whole MIB written up for it, including how you wanted the toast, and whether it was a bagel or Wonder Bread. I ended up with lots and lots of bread in my garage. It got a lot of attention, but I don’t think that managing your kitchen through SNMP is very practical today.“

Dave Buerger, who was an early tech journalist at CMP, remembers Interop with having “a strange sense of awe unfolding for everyone as we glimpsed the possibilities of global connectivity. Exhibits on the show floor were more experiments in connecting their booths to the rest of the world.”

Construction of the earliest Shownets (before 1993)

To say that Lynch was very persuasive is perhaps a big understatement. He convinced people that were quirky, unruly, or difficult to work with to spend lots of time pulling things together. “Dan allowed us to do stuff that the usual convention wouldn’t normally allow, and managed people that weren’t used to being managed,” said Malamud.

Peter de Vries was one of the earliest Shownet builders when he was working at Wollongong as one of the early internet vendors. He ended up working for Interop for three years before opening up the West Coast office for FTP Software. He remembers Lynch “dragging people kicking and screaming into using the internet back in the late 1980s and early 1990s. “But he was a fun guy to work for, and he had an unusual management style where he didn’t issue demands but convinced you to do something through more subtle suggestions, so by the time you did it you were convinced you had the original idea.”

These volunteers would essentially be working year-round, especially once the calendar was filled with multiple shows per year. Back in those early years, the convention centers didn’t care about cabling, and hadn’t yet figured out that having a more permanent physical networking plant could be used as an asset for attracting future meetings. ”We were often the first show to hang cables from the ceiling, and it wasn’t easy to do,” said Malamud, who chronicled the 1991 Shownet assembly. (6) The first Interop shows made use of thick Ethernet cables that required a great deal of finesse to work with. de Vries recalls they had to pass wires through expansion joints and other existing holes in the walls and floors, wires that didn’t easily bend around corners. “Each network tap took at least ten minutes of careful drilling to attach to this thick cable.” He has many fond memories of Lynch: “My goal was to try to get everyone to use TCP/IP, but Dan took it to the next step and show that TCP could be a useful tool, something better than a fax. He was a real visionary.”

These volunteers would essentially be working year-round, especially once the calendar was filled with multiple shows per year. Back in those early years, the convention centers didn’t care about cabling, and hadn’t yet figured out that having a more permanent physical networking plant could be used as an asset for attracting future meetings. ”We were often the first show to hang cables from the ceiling, and it wasn’t easy to do,” said Malamud, who chronicled the 1991 Shownet assembly. (6) The first Interop shows made use of thick Ethernet cables that required a great deal of finesse to work with. de Vries recalls they had to pass wires through expansion joints and other existing holes in the walls and floors, wires that didn’t easily bend around corners. “Each network tap took at least ten minutes of careful drilling to attach to this thick cable.” He has many fond memories of Lynch: “My goal was to try to get everyone to use TCP/IP, but Dan took it to the next step and show that TCP could be a useful tool, something better than a fax. He was a real visionary.”

Ethernet — in all of its variations over the years, including early implementations of 10BaseT and 100-megabit speeds — wasn’t the only cabling choice for Interop: the show would expand to fiber and Token Ring cabling as part of its mission. Brian Chee was one of those volunteers and remembers having to re-terminate 150 different fiber strands across the high catwalks of the convention spaces. “We even had to terminate the fiber on the roof of the convention center to connect it to the Las Vegas Hilton across the street,” he said.

Getting all that cabling up in the air wasn’t an easy task either. Patrick Mahan worked on the San Francisco show in 1992 and recalls that he and other networking volunteers were paired with the union electrical workers on a series of scissor lifts. “We needed multiple lifts operating in tandem to raise them, and we had just started hanging a 100-foot length when a loud air-horn goes off and each lift immediately starts descending to the floor, because it was time for the mandatory union 15-minute break. It took about three minutes before the cable bundles stared breaking apart and crashing to the cement floor. You could hear the glass in the fiber cables breaking!”

The Vegas climate made installations difficult, especially when its non-air-conditioned convention halls reached temperatures of 110 degrees F. outside. “Many convention centers don’t turn on their air conditioning until the night before the show begins, so it was a particularly harsh environment,” said Glenn Evans, who worked as both a volunteer and an employee of Interop during the late 1990s and early 2000s. “Vegas in May is very dry, and static electricity is a big issue. We fried several switch ports inadvertently and spent long nights adding static filters to avoid this because some shows had more than 1,200 connections across their networks.” Evans emphasized that the install teams relied on “redneck engineering to come up with creative solutions, and it didn’t have to be perfect, just had to work for five days.”

The cabling had to be laid out three times for each Shownet. The volunteers would have access to the convention center for a day months before any actual show. They would lay out the first cable segments and add connectors, then roll them up and store them in a warehouse. Then before the show there would be a “hot staging” event where the cables were connected to their equipment racks and tested. Finally, several nights before the show began was the real deployment at the convention center, which would span several 24-hour days before the actual opening. Those long nights were epic: de Vries recalls falling asleep in the middle of one night at the top of a 15-foot ladder, only to be gently awakened by the only other person in the convention center at the time. “Those installations nearly killed me!”

Many of the participants during those early years were motivated by a sense of common purpose, that their efforts were directly contributing to the internet and its usefulness. “I loved that we could help the overall industry get stuff right,” said Hultquist. “They were some of the smartest people that I have ever worked with and were constantly pushing the envelope to try to deploy all sorts of emerging technologies.”

But the physical plant was just one issue: once the cabling was in place, the real world of getting equipment up and running across these networks was challenging. In those early Interops, equipment was often at the bleeding edge, and engineers would make daily or even minute-by-minute changes to their protocol stacks and application code.

James van Bokkelen was the president of FTP Software and recalls seeing the Shownet in 1988 crash while running BSD v4.3, thanks to a buggy version of one TCP/IP command. Turns out the bug was present in Cisco’s routers that were used on the Shownet. “It took a few minutes of scampering before everything was in place and we got Shownet back online,” he said. Scampering indeed: the volunteers had to compare notes, debug their code, and reboot equipment often located at different ends of the convention floor.

“We were getting alpha software releases during the show. This network created an environment where people had to fix things in real time in real production environments,” said Hultquist. “Wellfleet, 3Com and Cisco were all sending us router firmware updates so their gear could interoperate with each other. I loved that we could help the overall industry get stuff right.”

At one of the 1991 Interops, “FDDI completely melted down,” said Merike Kaeo, who at the time was working for Cisco in charge of their booth and also volunteering in the NOC. “There was some obscure bug where a router reboot wasn’t enough, you had to reset the FDDI interface adapter separately. It didn’t take all that long to get things running, thankfully.”

Some of the problems were far more mundane, such as using equipment with NiCad batteries that had very short shelf life. Chee recalls that one Fluke engineering director who got tired of trying to get these replaced with Lithium-ion batteries. “He would send his team up to the rafters with network test equipment that had very short battery life; they were quickly replaced in their newer products.”

As more Shownets were brought up over the years, they had built-in redundant — and segregated — links. “We all played a part to make sure that after 1991, we would have a stable portion that would run reliably and put any untested equipment on another network that wouldn’t bring the working network down once the show started,” said Bill Kelly, who worked for Cisco in its early days.

de Vries said the first couple of Interop Shownets had less than 10 miles of cabling, which grew by 1991, according to Malamud, to having more than 35 miles of cabling, connecting a series of ribs, each one running down an aisle of the convention floor or some other well-defined geographic area. “Each rib had both Ethernet and Token Ring, connected to an equipment rack with various routers,” said Malamud. “There were two backbones that connected 50 different subnets, one based on FDDI and the other on Ethernet, which in turn were connected via T-1 lines to NASA Ames Research Center and Bay Area internet points.”

Bill Kelly, who worked on the Shownet NOC while he was at Cisco at the time, developed a three-stage model that covered a product lifecycle. “The first stage is using the IETF RFCs to try to make something work. Then the second stage is when a vendor is late to market and must figure out how to play nice with the incumbents and the standards. The third stage is mostly commodity products, and everything works as advertised.”

The middle years (1994-1999)

The internet – and Interop – were both growing quickly during this time period. New internet protocols and RFCs were being created frequently, and applications – and dot com businesses – sprang up without any business plans, let alone initial paying customers. There were new venues each year in Europe, shows in Sydney, Australia, and Singapore and Sao Paulo, Brazil. Some years had as many as seven or eight different shows, each with its own Shownet that needed to be customized for the particular exhibit halls in these cities.

Let’s return to 1986 for a moment. This is when Novell began its own trade shows called NetWorld to explain its growing Netware community. By 1994, these had grown, and that is when Novell and Interop merged their shows, calling them NetWorld+Interop. This moniker held until 2004, when Interop was purchased by a series of technical media companies. “Shownet didn’t change much after the Novell merger,” said Hultquist. “We could accommodate their stuff at the edge, but it didn’t impact the core network.” For the Shownet team, Netware was just another protocol to interoperate across. Despite Novell’s influence, during these years, TCP/IP became a networking standard. So did the cabling that made up the Shownet: “In the mid-1990s, a lot of the cable plant could be reused from show to show, with a standard set of 29-strand multimodal fiber with quick connectors and 48 strands of copper cat 5 for the ribs,” said Evans.

TCP/IP evolved too: by the end of the 1990s, the protocols and Ethernet hardware became a commodity and were both factory-installed in millions of endpoint devices. “The internet was becoming more standardized, and Interop became less of an experiment and more of a technology demonstration,” said Evans.

Nevertheless, vendors tried to differentiate themselves with query exhibits, pushing the envelope of connectivity. One stunt happened during the 1995 Interop at the Broadcom booth, which demonstrated Ethernet signals over barbed wire. “The wires were ugly and rusty and had nasty little barbs all over them,” according to one description written years later. (7)

Nevertheless, vendors tried to differentiate themselves with query exhibits, pushing the envelope of connectivity. One stunt happened during the 1995 Interop at the Broadcom booth, which demonstrated Ethernet signals over barbed wire. “The wires were ugly and rusty and had nasty little barbs all over them,” according to one description written years later. (7)

By 1999, the Shownet split into two separate parts: the live production network connecting the exhibit booths called InteropNet and InteropNet Labs used for connecting new products. Back then, this included VoIP, VPNs and other “hot technologies,” according to a post by Tim Greene in CNN. (8) This was because of several market forces: First, more and more conferences began promoting the idea of internet connectivity for both attendees and vendor participants. “As that reality dawned on people, the Interop Shownet became an increasingly useless anachronism,” said Larry Lang, who was part of the team building Cisco’s support for FDDI at that time. “As our competition became Wellfleet rather than IBM, why would we want to participate in an expensive and time-consuming display that suggested complete equivalence among all the products?”

Hultquist was quoted in that CNN piece saying that attendees “won’t know whether a piece of equipment really worked because of the demands placed on them by more experimental or untested products.”

A second issue had to do with striking a balance between established vendors and newcomers. Kelly remembers the relationship between Cisco and Interop to be “complicated because we were the market leader and if we just donated equipment without any technical support we ran the risk of outsiders misconfiguring the devices. Interop was also used to dealing with small engineering groups and not pesky marketing types that wanted to know the value of participating in the show.” Plus, long-running contributors to the original Shownets often got a jump on developing new gear and interacting with products that weren’t yet on the market.

The new millennium of Interop

Interop continued to grow in the new millennium. There were two notable events affecting the Shownet. The day the towers fell in New York was also the start of the fall Interop Atlanta show back in 2001. Many of the Shownet volunteers recall how quickly their network became the main delivery of news and video feeds to those attendees that were stuck in Atlanta, since all flights were grounded for the next several days. Brian Chee remembers that “within minutes of the disaster we maxed out the twin OC-12 WAN connections into the Shownet. We brought up streaming video of CNN Headline news over IP multicast that cut our wide-area traffic substantially, at the same time being an impressive demonstration of that technology.”

But then a few years later another event happened. “The day the Slammer virus hit, back in 2003, we had just gone production across the Shownet. That virus hurt our network throughput just enough that all our monitoring devices were useless,” said Chee. “But the NOC team was able to characterize the problem within a few minutes, and we were able to use air gapped consoles to reset routers and filter out the virus-infected packets.” That is as real world as it gets and is an example of how the Shownet proved its worth, time and time again.

“The coolest thing we got out of working at Interop is that technology doesn’t happen without the people, and the people involved were some of the hardest working and smartest people that you’ll ever meet. They checked their egos at the door, and solved problems jointly,” said Evans. “It was run like a democratic dictatorship, where everyone had a say.”

I didn’t attend this summer’s Tokyo Interop, but have asked for reports that will be added when this article runs later this year.

Acknowldgements. This is a draft of an upcoming article in the Internet Protocol Journal. This article wouldn’t be possible without the help of numerous volunteers and staff at Interops of the past, including:

Bill Alderson, Karl Auberbach, Dave Buerger, Brian Chee, Dave Crocker, Peter J.L. de Vries, Glenn Evans, Sharon Fisher, Connie Fleenor, Steve Hultquist, Merike Kaeo, Bill Kelly, Larry Lang, Brian Lloyd, Carl Malamud, Jim Martin, Naoki Matsuhira, Ryota Roy Motobayashi, and James van Bokkelen,

We are posting it here for comments, and would urge those of who have been inadvertently left out of the narrative to either post your comments here or send them to me privately. Thanks for your help!

Footnotes:

- http://motobayashi.net/interop/, Ryota Motobayashi has kept track of each show on his website, which also includes network diagrams and dates and places.

- https://books.google.gr/books?id=cJdcbp0zqnkC&lpg=PA97&dq=%22sharon%20fisher%22%20%22dan%20lynch%22&pg=PA97#v=onepage&q=%22sharon%20fisher%22%20%22dan%20lynch%22&f=false, Sharon Fisher ComputerWorld, October 7, 1991.

- https://spectrum.ieee.org/osi-the-internet-that-wasnt

- https://books.google.com/books?id=szsEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PT17&lpg=PT17&dq=%22sharon+fisher%22+%22interoperability+conference%22&source=bl&ots=ATqq8ZwL6P&sig=ACfU3U14wJEWFjEMHzw0dpz8e6isz5HBow&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwirwt2nkoqEAxUejYkEHe0RDkEQ6AF6BAgMEAM#v=onepage&q=%22sharon%20fisher%22%20%22interoperability%20conference%22&f=false, Sharon Fisher Infoworld, Ocotober 10, 1988.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110807173518/http://aboba.drizzlehosting.com/internaut/pc-ip.html

- https://museum.media.org/eti/RoundOne01.html

- http://www.cnn.com/TECH/computing/9905/11/nplusi1.idg/index.html, Tim Greene, CNN, May 11, 1999.

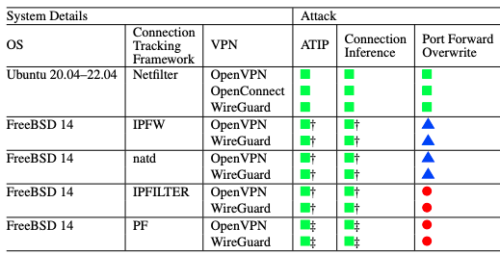

As you can see from the chart below, it goes to the way modern VPNs are designed and depends on Network Address Translation (NAT) and how the VPN software consumes NAT resources to initiate connection requests, allocates IP addresses, and sets up network routes.

As you can see from the chart below, it goes to the way modern VPNs are designed and depends on Network Address Translation (NAT) and how the VPN software consumes NAT resources to initiate connection requests, allocates IP addresses, and sets up network routes. In August 1986, a few very motivated people got the bright idea to teach others how to implement the early internet protocols. This first conference, called the TCP/IP Vendors Workshop, was held in Monterey California and was by invitation only. (Agenda photocopy) Speakers included Vint Cerf (who was at MCI), Jon Postel (RFC Editor and at ARPANET before playing a key role in internet administration), and Paul Mockapetris and Bob Braden (both at USC-ISI).

In August 1986, a few very motivated people got the bright idea to teach others how to implement the early internet protocols. This first conference, called the TCP/IP Vendors Workshop, was held in Monterey California and was by invitation only. (Agenda photocopy) Speakers included Vint Cerf (who was at MCI), Jon Postel (RFC Editor and at ARPANET before playing a key role in internet administration), and Paul Mockapetris and Bob Braden (both at USC-ISI).

These volunteers would essentially be working year-round, especially once the calendar was filled with multiple shows per year. Back in those early years, the convention centers didn’t care about cabling, and hadn’t yet figured out that having a more permanent physical networking plant could be used as an asset for attracting future meetings. ”We were often the first show to hang cables from the ceiling, and it wasn’t easy to do,” said Malamud, who chronicled the 1991 Shownet assembly. (6) The first Interop shows made use of thick Ethernet cables that required a great deal of finesse to work with. de Vries recalls they had to pass wires through expansion joints and other existing holes in the walls and floors, wires that didn’t easily bend around corners. “Each network tap took at least ten minutes of careful drilling to attach to this thick cable.” He has many fond memories of Lynch: “My goal was to try to get everyone to use TCP/IP, but Dan took it to the next step and show that TCP could be a useful tool, something better than a fax. He was a real visionary.”

These volunteers would essentially be working year-round, especially once the calendar was filled with multiple shows per year. Back in those early years, the convention centers didn’t care about cabling, and hadn’t yet figured out that having a more permanent physical networking plant could be used as an asset for attracting future meetings. ”We were often the first show to hang cables from the ceiling, and it wasn’t easy to do,” said Malamud, who chronicled the 1991 Shownet assembly. (6) The first Interop shows made use of thick Ethernet cables that required a great deal of finesse to work with. de Vries recalls they had to pass wires through expansion joints and other existing holes in the walls and floors, wires that didn’t easily bend around corners. “Each network tap took at least ten minutes of careful drilling to attach to this thick cable.” He has many fond memories of Lynch: “My goal was to try to get everyone to use TCP/IP, but Dan took it to the next step and show that TCP could be a useful tool, something better than a fax. He was a real visionary.” Nevertheless, vendors tried to differentiate themselves with query exhibits, pushing the envelope of connectivity. One stunt happened during the 1995 Interop at the Broadcom booth, which demonstrated Ethernet signals over barbed wire. “The wires were ugly and rusty and had nasty little barbs all over them,” according to one description written years later. (7)

Nevertheless, vendors tried to differentiate themselves with query exhibits, pushing the envelope of connectivity. One stunt happened during the 1995 Interop at the Broadcom booth, which demonstrated Ethernet signals over barbed wire. “The wires were ugly and rusty and had nasty little barbs all over them,” according to one description written years later. (7)