Jack Posobiec, Mike Benz, Justine Sacco, Samara Duplessis. If you have never heard of any of these people, this post might be illuminating about how online conspiracies are created and thrive. It is based on a new book, Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies into Reality,” by Renee DiResta, a computer science researcher whom I have followed over many years. DiResta has been involved in debunking various memes, such as Pizzagate, “stolen” elections, anti-vaxxers, Wayfair selling kids inside their filing cabinets and numerous other cabals. It is now quite possible to mass-produce unreality.

Her book describes the toxic mixture of influencers, algorithms and crowd responses to construct various intricate and believable online conspiracies. She calls this unholy trinity a bespoke reality, used as a self-reinforcing mechanism that has been constructed over the years to cause a lot of pain and suffering for unsuspecting people. “Platforms have imbued crowds with new qualities. They are no long fleeting and local but persistent and global,” she writes. She herself has been the target of a few internet mobs, getting sued, doxxed, misquoted and more. Earlier this summer, she lost her job at the Stanford Internet Observatory, a research outfit she ran with Alex Stamos, who left last year. That link describes what SIO will become without their leadership, and it is debatable if the operation still really exists.

Clearly, “it is not a good time to be in the content moderation industry,” said 404 Media’s Jason Koebler. Trust and safety moderation teams are all but disbanded, and big consulting contracts to comb through the millions of toxic posts on various social networks aren’t being renewed. Facebook announced earlier this year they were shutting down CrowdTangle, its major research tool, to be replaced by something that may or not actually be useful. We all know what happened over at Twitter when it was bought by a billionaire man-boy, such as repricing API access to the Twitter APIs. What used to be free back in the Before Times now costs $42,000 a month. And new research from CheckMyAds indicate that advertisers there are returning back, only this time being shoehorned into comments, including comments of posts that violate its own content rules about hate speech.

@checkmyads Elon Musk’s X placed ads for dozens of brands in the replies below posts that violate the X Rules against hateful content. Here’s what we found when we looked of a sampling of posts.

It seems all social media have adopted a model of toxic influencer-as-a-service. “What matters is keeping fans engaged, aggrieved and subscribed,” says DiResta. She talks about how the influencer is not just telling the story, but becomes part of the story itself. They can adopt one of several roles or personas: the Entertainer, the Explainer, the Bestie, Idols, and Gurus. There are generals, who keep the mob all in a lather, and Reflexive Contrarians, a particular type of explainer that tell you why everything you know is wrong, and Propagandists, and the Perpetually Aggrieved. This latter type have a solid understanding of how platform algorithms amplify their content, and yet also can avoid their moderation efforts, when they cry “censorship” if they run afoul of them.

No matter what type of influencer one is, the real measure of success is when they amass a large enough audience they become like Enron, “too big to cancel.” At that point, truth and interest all become relative, and almost irrelevant, what she calls the Fantasy Industrial Complex, the cinematic universe that is no different from the comics.

But the cinematic universe has to have its villains to succeed. If you create an online service that focuses on a particular self-selected audience (say Parler as an example), you lose the ability to fight the others, and your perpetual complaints don’t land. “There is no opportunity to spin up an aggrievement fest over being wrongfully moderated,” she writes. By design, you can’t own your enemies. So sad.

The title of this post — “big if true” — refers to what influencers say in their rush to publish some content. “Experts may wait to be sure of something,” says DiResta. “But not influencers. And if this turns out to be false? Oh, well, they were just sharing their opinion and just asking questions.” Trolling is fun, and quite profitable, it turns out ” And it almost doesn’t matter if the statements actually advance a cause or prove anything. “The point is the fight. Winning insights, in fact, negatively impacts the influencer because resolution would reduce the potential for future monetizable content,” she writes.

This has several implications. We are no longer in the arena of freedom of speech: instead, we debate the freedom of reach. It isn’t about hosting content on a particular platform, but how it is promoted and packaged. We aren’t talking about the marketplace of ideas, but the way those ideas are manipulated.

DiResta’s book should be required reading for all PR and marketers. The last portion of her book has some very concrete suggestions on how to turn down the toxicity, and try to return to a bespoke world that actually has some basis in truth. If you don’t want to read it, I suggest watching the middle third or so of her interview with Quentin Hardy.And maybe re-evaluate your social media presence. “If we want virtual town squares” in our online world, she says “we have to act like the people on them are our actual neighbors.”

Your eCommerce website is vulnerable to a variety of threats known collectively as web skimming. The hackers behind these threats are getting better at penetrating your site and installing their malware to steal your customers’ money and private information. And web skimming is getting more popular both with the rising frequency of attacks and with bigger data breaches recorded. In this

Your eCommerce website is vulnerable to a variety of threats known collectively as web skimming. The hackers behind these threats are getting better at penetrating your site and installing their malware to steal your customers’ money and private information. And web skimming is getting more popular both with the rising frequency of attacks and with bigger data breaches recorded. In this

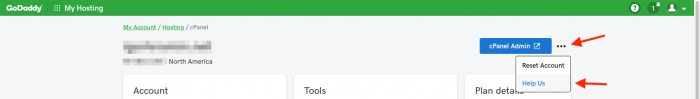

If you use GoDaddy hosting, you should go to your cPanel hosting portal, click on the small three dots at the top of the page (as shown above), click “help us” and ensure you have opted out.

If you use GoDaddy hosting, you should go to your cPanel hosting portal, click on the small three dots at the top of the page (as shown above), click “help us” and ensure you have opted out.

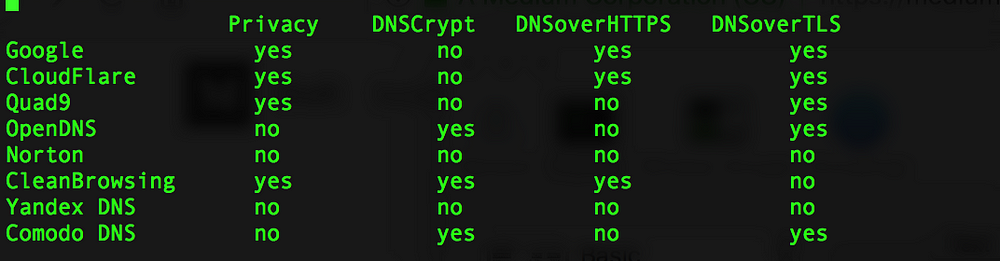

Back when I wrote that article, there was a growing need for providing better DNS services that were more secure and more private than the default one that comes with your broadband provider. But one of the great things about the Internet is that you usually have lots of choices for something that you are trying to do. Don’t like your hosting provider? Nowadays there are hundreds. Want to find a better server for some particular task? Now everything is in the cloud, and you have your choice of clouds. And so forth.

Back when I wrote that article, there was a growing need for providing better DNS services that were more secure and more private than the default one that comes with your broadband provider. But one of the great things about the Internet is that you usually have lots of choices for something that you are trying to do. Don’t like your hosting provider? Nowadays there are hundreds. Want to find a better server for some particular task? Now everything is in the cloud, and you have your choice of clouds. And so forth. As I mentioned earlier, he did a very thorough job testing the DNS providers from around the globe, using VPNs to connect to their service from 17 different locations. He found that all of the providers performed well across North America and Europe, but elsewhere in the world there were differences. Overall though,

As I mentioned earlier, he did a very thorough job testing the DNS providers from around the globe, using VPNs to connect to their service from 17 different locations. He found that all of the providers performed well across North America and Europe, but elsewhere in the world there were differences. Overall though,  This week the web has celebrated yet another of its

This week the web has celebrated yet another of its

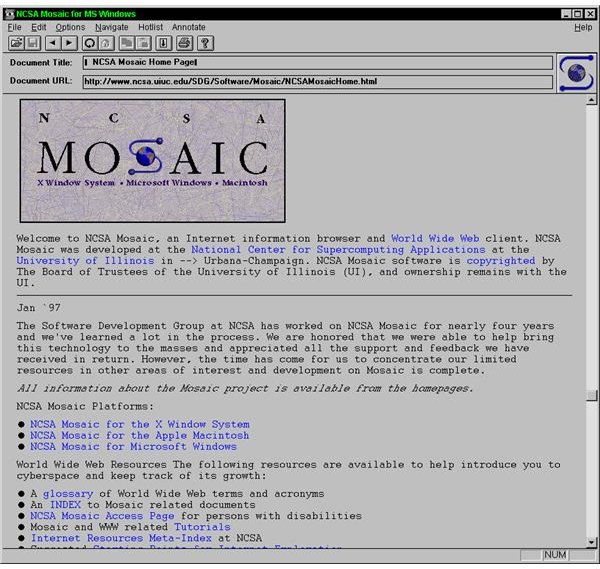

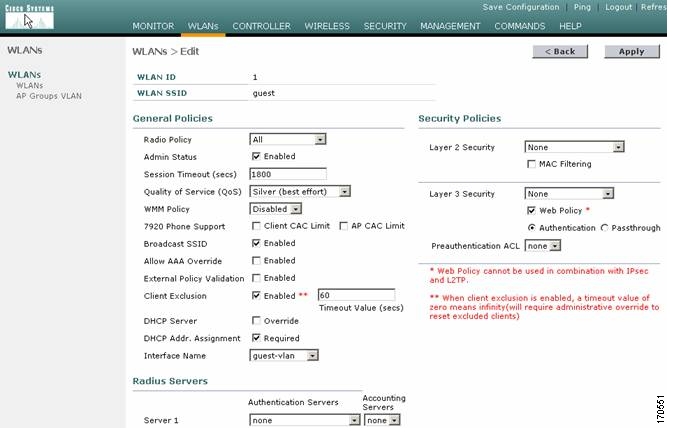

Today we almost take it for granted that numerous enterprise software products have web front-end interfaces, not to mention all the SaaS products that speak native HTML. But back in the mid 1990s, vendors were still struggling with the web interface and trying it on. Cisco had its UniverCD (shown here), which was part CD-ROM and part website. The CD came with a copy of the Mosaic browser so you could look up the latest router firmware and download it online, and when I saw this back in the day I said it was a brilliant use of the two interfaces. Novell (ah, remember them?) had its Market Messenger CD ROM, which also combined the two. There were lots of other book/CD combo packages back then, including Frontier’s Cybersearch product. It had the entire Lycos (a precursor of Google) catalog on CD along with browser and on-ramp tools. Imagine putting the entire index of the Internet on a single CD. Of course, it would be instantly out of date but you can’t fault them for trying.

Today we almost take it for granted that numerous enterprise software products have web front-end interfaces, not to mention all the SaaS products that speak native HTML. But back in the mid 1990s, vendors were still struggling with the web interface and trying it on. Cisco had its UniverCD (shown here), which was part CD-ROM and part website. The CD came with a copy of the Mosaic browser so you could look up the latest router firmware and download it online, and when I saw this back in the day I said it was a brilliant use of the two interfaces. Novell (ah, remember them?) had its Market Messenger CD ROM, which also combined the two. There were lots of other book/CD combo packages back then, including Frontier’s Cybersearch product. It had the entire Lycos (a precursor of Google) catalog on CD along with browser and on-ramp tools. Imagine putting the entire index of the Internet on a single CD. Of course, it would be instantly out of date but you can’t fault them for trying.