I am not so sure. For those of you keeping score at home, web v1 was the early days where we had web servers delivering static pages of mostly text, starting in the early 1990s and lasting until about 2003 or 2004. The next version was the dynamic web where we created our own content, and where we freely gave away our privacy and data so that we could post cat memes and dance videos to the now giants of Facebook /Apple/Amazon/Netflix/Google, otherwise called FAANG. (Facebook and Google have renamed themselves, but the acronym has stuck.)

But now it is time for a new iteration, and v3 attempts to create a more egalitarian internet, protected by encrypted tokens that can keep everyone’s identity and data private and secure. Say what? At least, that is the plan.

Whether or not you agree with this vision, it has largely been unrealized. Yes, there is a Web 3 Foundation, and you can see at that link a very complex tech stack that will consist of multiple protocol layers, much still TBD. For those of us that cut our teeth on HTML, CSS, and HTTPS, these protocols are pretty much unknown.

Scott Carey writes in Infoworld summing things up this way: “To access most Web3 applications, users will need a crypto wallet, most likely a new browser, an understanding of a whole new world of terminology, and a willingness to pay the volatile gas fees required to perform actions on the Ethereum blockchain. Those are significant barriers to entry for the average internet user.” I’ll say. If you have never had a crypto wallet, never used Rust or Solidity and don’t know what a gas fee is, you need to go to web3 study hall. You may not understand the tech behind it — I don’t fully understand all of these items — but that is the point. The decentralized web is being built on a series of protocols and there are a lot of gaps.

But let’s put aside all the new tech and answer a few basic questions.

What is the role of clients and servers? One of the first things you come to is needing to understand the difference between clients and servers. In the web1 and web2 worlds, there were browsers, and there were various servers (web, database, applications, payments, and so forth). It was a pretty clean separation of powers. Some of us were happy to never touch any kind of server, something that leads off Moxie Marlinspike’s “first impressions” blog post. I don’t agree with this position. I have been running my own web server for more than 25 years. I wouldn’t have it any other way. I like being “master of my domain” (which is more than just running my own server, such as being able to move it from one place to another across the internet, which I had to do last year when my ISP went out of business).

What is the role of clients and servers? One of the first things you come to is needing to understand the difference between clients and servers. In the web1 and web2 worlds, there were browsers, and there were various servers (web, database, applications, payments, and so forth). It was a pretty clean separation of powers. Some of us were happy to never touch any kind of server, something that leads off Moxie Marlinspike’s “first impressions” blog post. I don’t agree with this position. I have been running my own web server for more than 25 years. I wouldn’t have it any other way. I like being “master of my domain” (which is more than just running my own server, such as being able to move it from one place to another across the internet, which I had to do last year when my ISP went out of business).

I think what Moxie meant to say is that most people don’t like configuring and maintaining their own servers. But that is why we have ISPs.

But look at the tech stack that we are promised with web3: that is a lot of tech to deal with. If we had resistance to configuring HTML and HTTP, imagine what amount of pain we will be faced when all this new stuff comes to fruition?

Lance Ulanoff writes that the vision for web3 is “more a combination of edgy new technology and a reaction to centralized control.” He goes on to discuss some of the early descriptions before the web3 term came into the popular lexicon, such as the semantic web that was tossed around back in 2006. He describes web3 being when we can control our interactions and have a universal identity across all systems. That’s nice, but so much of the current vision about web3 doesn’t really fill in the blanks about how this control will happen or how we can create these universal identities. Moxie says that we need to use cryptography rather than infrastructure to distribute trust. I completely agree. Ignoring the trust issues is dangerous — look how long it has taken us to resolve email trust issues, and those protocols were created decades ago.

But how this infrastructure play out brings us to my next question:

What is the role of peer-to-peer (p2p) technology? Remember Napster and peer file sharing of music and videos? Back then (roughly 2000-2005), everyone was digitizing their CDs, or stealing music from others, or both. Napster and LimeWire and the other apps created peer file servers on your hard disk, and you then shared your digitized content with the world. Sharing wasn’t caring, and lawsuits ensued. Now we just pay Netflix et al. and stream the content when we want to listen or watch something. Who needs possession of the actual bits?

But see what has happened here: we went from this idealized p2p world to today where just a few centralized businesses (like FAANG) run the show. This could be the fate of web3, and all this talk about a decentralized, egalitarian web could fall apart. Today’s crypto/NFT world depends on just a few centralized service providers, and the distinction between client and server in a fully decentralized p2p blockchain isn’t all that clear, as one of the Ethereum founders Vitaly Buterin points out. He says that there are various gaps in web3 which are bridged with the various API suppliers, such as Infura and Opensea. The issue that Moxie has is that many NFT and crypto advocates have just accepted the role of these API vendors without much thought about the implications. Moxie is worried that these vendors have a lot of control over things, and that there is the potential for the decentralized web3 to turn into a less efficient and less private version of today’s internet. Think of one nightmare scenario, where Facebook (or one of the other giants) has its own web3 servers, APIs, and alt-coins. The horror!

But you think crypto is cool, and there is money to be made. Now we get to the real meat of the matter. Forget about a more equal internet and singing kumbaya off into the sunset. Let’s talk about how high the various alt-coins are trading at – or not, depending on when you entered the market. Remember the internet bubble of 1999-2000, when domains were being bought and sold on little more than a pitch deck. That was Gold Rush v1, and all you had to do to participate was to buy a domain and flip it. (I am guilty of this, but I didn’t buy my domain to flip it. I just got lucky.) You could argue that all you need now is to hold a basket of crypto coins — as some of you have done. But look at all the knowledge you have to collect to participate in this gold rush. Nevertheless, there is some cool stuff that is being built, as this blogger documents. This post basically rebuts a few of Moxie’s complaints while making Moxie’s point that this is very early stuff.

So go cautiously into the web3 night, and good luck learning about all the requisite tech that will be needed. And for those of you complaining about the decentralized and private web of the future, you might want to spend some time doing the basic blocking and tackling and eliminating duplicate passwords and implementing MFA logins now, because you’ll need something like them to get on the blockchain train. Or at least protect all those crypto funds in your wallet from being lost or stolen.

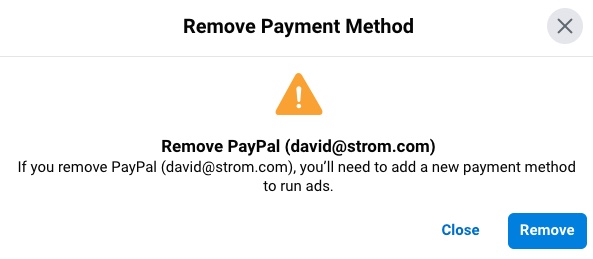

f you are looking to transfer money to someone quickly, you have a lot of choices, including Zelle, Venmo, Wise (form. Transferwise), Paypal and Xe.com. But with choice comes learning what is involved in using each vendor, including getting answers to the following questions:

f you are looking to transfer money to someone quickly, you have a lot of choices, including Zelle, Venmo, Wise (form. Transferwise), Paypal and Xe.com. But with choice comes learning what is involved in using each vendor, including getting answers to the following questions:

I asked my friend

I asked my friend