I have been a fan of the WWII effort to build special-purpose machines to break German codes for many yea rs, and last wrote about Colossus here, the two-room sized digital computer that was the precursor to the modern PC era. I first found out about this remarkable machine and the effort behind it with a 2007 book that you can still purchase from Amazon.

rs, and last wrote about Colossus here, the two-room sized digital computer that was the precursor to the modern PC era. I first found out about this remarkable machine and the effort behind it with a 2007 book that you can still purchase from Amazon.

But there is no substitute for actually visiting the hallowed ground where this all happened, which I finally did last weekend when I was in London on a consulting assignment. I was fortunate that I had a colleague (and avid reader) who lived nearby and was willing to take me around: he hadn’t been there in a while. I have included some photos that I took during my day at Bletchley Park, and it was great to finally see Colossus in all of its mechanical glory. As you can see from this photo, it looks more like an attic of used spare parts but I can assure it is quite a special place.

When most people think of decrypting codes, they think a “Matrix” style special effect where gibberish is turned into readable text (German in this instance). Or when you open a file and hit a button that will automatically decrypt the message. This is far from what happened in the 1940s. Back then, it was a herculean effort that involved recoding Morse code radio signals, transferring them to paper tape, using various cribs and cheat sheets to guess at the codes, and then processing the paper tapes through Colossus. What we also don’t realize is that these two rooms full of gear were built without anyone actually seeing the actual German Lorentz coding machine that was used to encrypt the messages to begin with. (The Bombe, a much simpler device, was used to decrypt Enigma codes.) It looks like a very strange machine, but obviously something that was designed to be carted around in the field to send and receive messages.

When most people think of decrypting codes, they think a “Matrix” style special effect where gibberish is turned into readable text (German in this instance). Or when you open a file and hit a button that will automatically decrypt the message. This is far from what happened in the 1940s. Back then, it was a herculean effort that involved recoding Morse code radio signals, transferring them to paper tape, using various cribs and cheat sheets to guess at the codes, and then processing the paper tapes through Colossus. What we also don’t realize is that these two rooms full of gear were built without anyone actually seeing the actual German Lorentz coding machine that was used to encrypt the messages to begin with. (The Bombe, a much simpler device, was used to decrypt Enigma codes.) It looks like a very strange machine, but obviously something that was designed to be carted around in the field to send and receive messages.

Sadly, the reconstructed computer is not doing very well. This is no surprise, given that it is made of thousands of vacuum tubes (what the Brits call valves, which evokes an entire Steam Punk ethos). Only a few segments of the process that was used for the decrypts could be demonstrated, and it seems a collection of volunteer minders is kept very busy at keeping the thing in some working order. Here you can see an illustration of what it took to use the Bombe machines, which were more mechanical and didn’t involve true digital computing.

If you decide to visit Colossus, you will need to go to two separate places that are only a short walk apart. The first is the Bletchley Park estate itself, where there are several outbuildings that contain curated exhibits about the wartime effort, including several tributes to the some of the thousands of men and women that worked there during the war. One of the more notorious was Alan Turing, and you can see a mock up of his office here. After the movie The Imitation Game came out, his popularity rose and the park was quite crowded, albeit it was a holiday weekend. There are copies of some of his mathematic al papers (shown below), a brick wall that honors many of the park’s contributors, and the formal apology letter from the British government that cleared his name. Turing’s 1950 paper was one of the seminal works in the history of digital computing and was also shown in one of the exhibits. What I found fascinating was how much of this stuff was being soaked up by the ordinary folks that were wandering around the park. I mean, I am a geek but there were school kids that were absorbed in all of this stuff.

al papers (shown below), a brick wall that honors many of the park’s contributors, and the formal apology letter from the British government that cleared his name. Turing’s 1950 paper was one of the seminal works in the history of digital computing and was also shown in one of the exhibits. What I found fascinating was how much of this stuff was being soaked up by the ordinary folks that were wandering around the park. I mean, I am a geek but there were school kids that were absorbed in all of this stuff.

One of the lesser-known individuals that was honored at the park was a double agent that was known by Garbo, because he was such an impressive actor. I read this book not too long ago about his exploits, and he played key roles in the war effort that had nothing to do with computers. He invented entire networks of imaginary spies when he filed his reports with the Germans that were so convincing that they moved their troops before D-Day, thus saving countless Allied lives.

But the entry to the park doesn’t get you to the reconstructed Colossus, and for that you have to walk down the road and pay another fee to gain access to the British computer history museum. It has numerous other exhibits of dusty old gear, including the first magnetic disks that held a whopping 250 MB 2 MB of data (I think it was mislabeled) and were the size of a small appliance. It was interesting, although not as much fun nor as comprehensive as the museum in San Jose, California. I hope you get a chance to visit both of the Bletchley places and see for yourself how computing history was made.

Malware authors have gotten more clever and sneaky over time to make their code more difficult to detect and prevent. One of the more worrying recent developments

Malware authors have gotten more clever and sneaky over time to make their code more difficult to detect and prevent. One of the more worrying recent developments

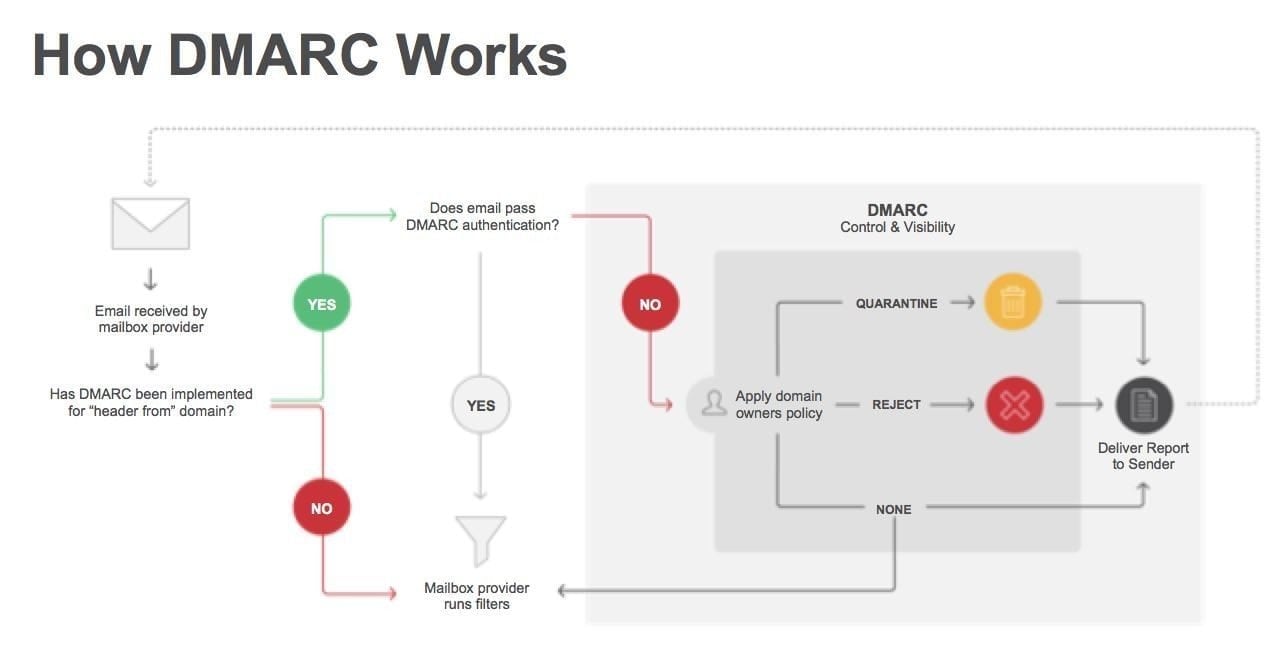

Phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunities for hackers to enter the network. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking scripts, data leakages, or privilege escalation exploits. Despite making some progress, a trio of email security protocols has seen a rocky road of deployment in the past year. Going by their acronyms SPF, DKIM and DMARC, the three are difficult to configure and require careful study to understand how they inter-relate and complement each other with their protective features. The effort, however, is worth the investment in learning how to use them.

Phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunities for hackers to enter the network. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking scripts, data leakages, or privilege escalation exploits. Despite making some progress, a trio of email security protocols has seen a rocky road of deployment in the past year. Going by their acronyms SPF, DKIM and DMARC, the three are difficult to configure and require careful study to understand how they inter-relate and complement each other with their protective features. The effort, however, is worth the investment in learning how to use them. This week we review what Facebook could be doing to make things better for all of us. Its problems have been well documented, from privacy violations to a massive sell-off in its stocks to untrustworthy comments from its CEO. It’s CMO position has remained open for most of the year, prompting them to

This week we review what Facebook could be doing to make things better for all of us. Its problems have been well documented, from privacy violations to a massive sell-off in its stocks to untrustworthy comments from its CEO. It’s CMO position has remained open for most of the year, prompting them to

This week we talk about new ways that machine learning and artificial intelligence can benefit marketing organizations. While these three news items are all different aspects of this technology, they show collectively how these new technologies are changing the way marketing is done.

This week we talk about new ways that machine learning and artificial intelligence can benefit marketing organizations. While these three news items are all different aspects of this technology, they show collectively how these new technologies are changing the way marketing is done.