Last week, IBM sold off its Domino/Notes software business unit to HCL. While you probably haven’t heard of them, they are a billion dollar Indian tech conglomerate. Sadly, this represents the end of one era for Notes. It certainly has had a long and significant life span.

“Notes’ longevity is amazing,” says David DeJean, who co-wrote one of the first books about it back in 1991. “What other corporate software product has had that kind of run? Notes’ success started with its chameleon-like ability to go into a company and work the way the company worked. It let companies computerize their operations at their own pace. Other software packages have been the software of “No” where Notes was almost always the software of ‘Sure.’”

I was present at its conception in the late 1980s, when Ray Ozzie had the idea for what was then an unknown software category that was labeled at the time as groupware. It was the first time that a PC software program could be used to connect multiple computers in a meaningful way, and be used to create applications that leveraged the group. DeJean recalled that these apps were at the heart of what made Notes work: “During a crucial moment in the computerization of the enterprise in the 1990s, Notes applications proliferated like rabbits. It was very easy for companies to get into Notes, and very hard to get out.”

When Notes came out. I was working as an editor at PC Week. My colleague Sam Whitmore told me that “it took us a while to get our brains around the idea of its replication feature. Most of us found it redundant to email.” That was its biggest challenge, and well into its middle age Notes’ biggest competitor continued to be ordinary email. Many of my press colleagues carried a long-standing hatred for it. Nevertheless, Whitmore also recalls that “Lotus appreciated how technical we were, that we understood what Ray Ozzie was bringing to the world. Perhaps because of this, Lotus offered PC Week a lot of money to produce a special report on Notes.”

I had first-hand experience using Notes when I worked at CMP in the early 2000’s when I was an editor at VAR Business and also at EETimes. The CMP IT department had written quite a few Notes applications for various editorial and sales tracking purposes, again showing how extensible it could be.

This is something that many of its critics didn’t really understand, both then and now. One of its earliest customers was PriceWaterhouse, now PwC. Sheldon Laube was running the IT operation there and made the decision to purchase 10,000 copies of Notes back in 1990. He told me that this “started a transformation at the firm. Notes was truly the first personal computer software product that changed the nature of how people used PCs. Until Notes came along, PCs were personal productivity tools, with the majority of uses being spreadsheets, word processing and presentations. Notes created a social use for personal computers and enabled teams of people, spread across geographies, to communicate, collaborate and share information in a way which was not possible previously. It was the tool that moved PCs and networks onto every desk in every office of PW around the world.”

This is an important point, and one that I didn’t think much about until I started corresponding recently with Laube. If you credit Notes as being the first social software tool, it actually predates Facebook by more than a decade. Even MySpace, which was the largest social network for a few years (and had more traffic than Google too), was created in the early 2000s.

Notes was also ahead of its time in another area. “Notes was a precursor to both the web and social media,” says Laube. “It was all about easily publishing and sharing information in a managed way suited to business use. It is the ease of management and the ability to control information access within Notes securely which allowed its rapid adoption by business.” Laube reminded me that back then, information security was barely recognized as necessary by IT departments.

This isn’t completely an accurate picture, mainly because Notes was focused on the enterprise, not the consumer. Notes “mixed email with databases with insanely secure data replication and custom apps,” said David Gewirtz in his column this week for ZDnet. He was an early advocate of Notes and wrote numerous books and edited many newsletters about its enterprise use. “It was enterprise software before enterprise software was cool.” He wrote about how Notes had elements of Salesforce, Dropbox, Atlassian, Zendesk and ServiceNow — years before any of these products were even invented. Another aspect of Notes that doesn’t get much attention is its integrated group calendars and contacts. Now we take these elements for granted — until they don’t work — and expect them in many communications tools. Back in the early 1990s, this was a rare feature. Scott Mace, who runs the site CalendarSwamp, remembers complaining about how hard shared calendars were back in the late 1990s, and how Notes was an early standout then.

Notes has gone through many transitions in its long life: After IBM acquired it, Big Blue extended the software to Domino, which combined Notes with web services and eventually was used to provide a managed hosting solution as well. Ozzie told me that Notes was in essence an amazingly powerful applications server with captive clients. This differed from the web model, where web clients were free and Netscape and others made money from selling their own application servers. IBM added the web server because they had to: Ozzie said if they hadn’t, Notes would have died quickly in the web era. Instead, it still flourishes.

Another thing that doesn’t get much attention is that IBM believed so much in Notes that it made it its corporate communications standard for many years. One of their reasons — and a major motivation for many other customers — is that Notes offered an end-to-end encrypted email system, something that wasn’t common at the time.

Even so, IBM was a poor fit for Notes because it was too slow to innovate. While having a web front-end solved one big problem for Notes (its very thick client software), it wasn’t enough to compete against the world of open source and the rich software development of the web. As the web took over the software world, Notes became more of an anachronism, and more nimble solutions (including one product called Nimble, btw) became more attractive to corporate software developers. Ozzie said, “Shame on IBM for losing the corporate email market” to Microsoft and then Google. He reminded me that back then, we had different email systems that couldn’t connect with each other, even within the same office.

Betsy Kosheff, who did PR for Lotus back when it was sold to IBM, told me, “IBM had no business doing software innovation. That point was very obvious right from the acquisition. It’s not their fault – IBM is just not designed that way. I imagine their India-based buyer will be looking for more operational efficiencies. They’re probably not looking for the next big idea, which is what was so much fun about Notes and being part of that product in the early days. I’m not saying you can’t possibly create an entrepreneurial division with exciting innovations from within a larger company. I’m just saying they didn’t do it at IBM and probably not at any other billion dollar IT company.”

Ozzie reminded me that when Lotus was sold to IBM, they were in a head-to-head battle with Exchange. Microsoft had the edge because they owned the operating system and had majority share with office applications. IBM could offer a broader software portfolio that could attract customers.

Was Notes too early for its time? Ozzie says no: “I am just pleased that things have continued to evolve in collaboration tools.There are still things related to human interaction, such as distributed trust and managing overload that we first learned in Notes that have yet to be embraced by anything in the enterprise social world.”

eventually became the BlackBerry. It worked with a one-pound radio and a one pound HP palmtop.

eventually became the BlackBerry. It worked with a one-pound radio and a one pound HP palmtop. book with Marshall Rose, the inventor of the POP protocols. The book covered the more popular email programs at the time, which included Lotus cc:Mail (extinct), Netscape Messenger (extinct but replaced by Thunderbird you could say), Eudora Pro (still very much

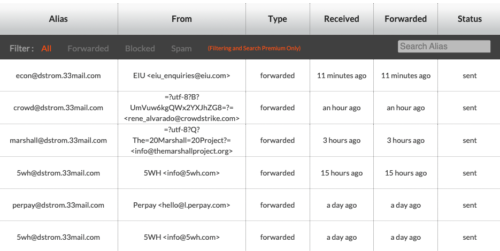

book with Marshall Rose, the inventor of the POP protocols. The book covered the more popular email programs at the time, which included Lotus cc:Mail (extinct), Netscape Messenger (extinct but replaced by Thunderbird you could say), Eudora Pro (still very much  Here are three providers you should check out: DuckDuckGo’s @duck.com, 33Mail.com, and Yahoo.com. All three are available for free (and the latter two also offer paid plans) and work reasonably well. My favorite is 33Mail, which I have been an avid user of their free account for many years now and have set up dozens of aliases. The setup process is nothing: you just start using “something@youraccount.33mail.com” and the service takes care of getting the message forwarded to your real email. The forever free version has unlimited aliases, which is handy because it shows you the alias used at the top of your message, in case you want to send all inbound mail using that alias to the bit bucket. You can sign into the web portal of your account and view the transaction log shown here as well as the status of the various aliases that have been used to forward mail to you, and those emails that you have blocked. The free account does come with bandwidth limits, which I have never come close to reaching. There are

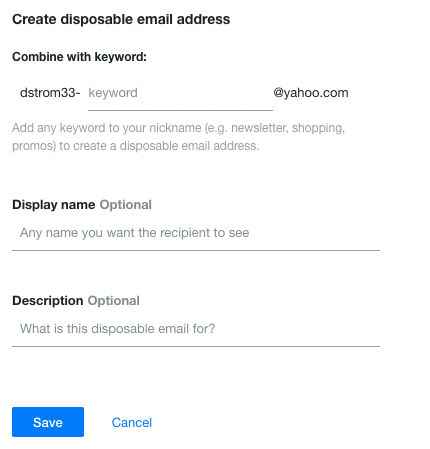

Here are three providers you should check out: DuckDuckGo’s @duck.com, 33Mail.com, and Yahoo.com. All three are available for free (and the latter two also offer paid plans) and work reasonably well. My favorite is 33Mail, which I have been an avid user of their free account for many years now and have set up dozens of aliases. The setup process is nothing: you just start using “something@youraccount.33mail.com” and the service takes care of getting the message forwarded to your real email. The forever free version has unlimited aliases, which is handy because it shows you the alias used at the top of your message, in case you want to send all inbound mail using that alias to the bit bucket. You can sign into the web portal of your account and view the transaction log shown here as well as the status of the various aliases that have been used to forward mail to you, and those emails that you have blocked. The free account does come with bandwidth limits, which I have never come close to reaching. There are  Finally, there is Yahoo. Remember them? Remember both of their massive data breaches back in the day? Well, it has been years since I used them for anything other than a spam collector, and the free version immediately begins placing ads in the form of a rolling series of messages at the top of your inbox. (You can remove these if you upgrade to a paid plan.) You can setup three aliases (what Yahoo calls “keywords”) on your account, using this menu shown here. It isn’t as convenient as 33Mail, and of course you need a Yahoo email address for this to work.

Finally, there is Yahoo. Remember them? Remember both of their massive data breaches back in the day? Well, it has been years since I used them for anything other than a spam collector, and the free version immediately begins placing ads in the form of a rolling series of messages at the top of your inbox. (You can remove these if you upgrade to a paid plan.) You can setup three aliases (what Yahoo calls “keywords”) on your account, using this menu shown here. It isn’t as convenient as 33Mail, and of course you need a Yahoo email address for this to work.

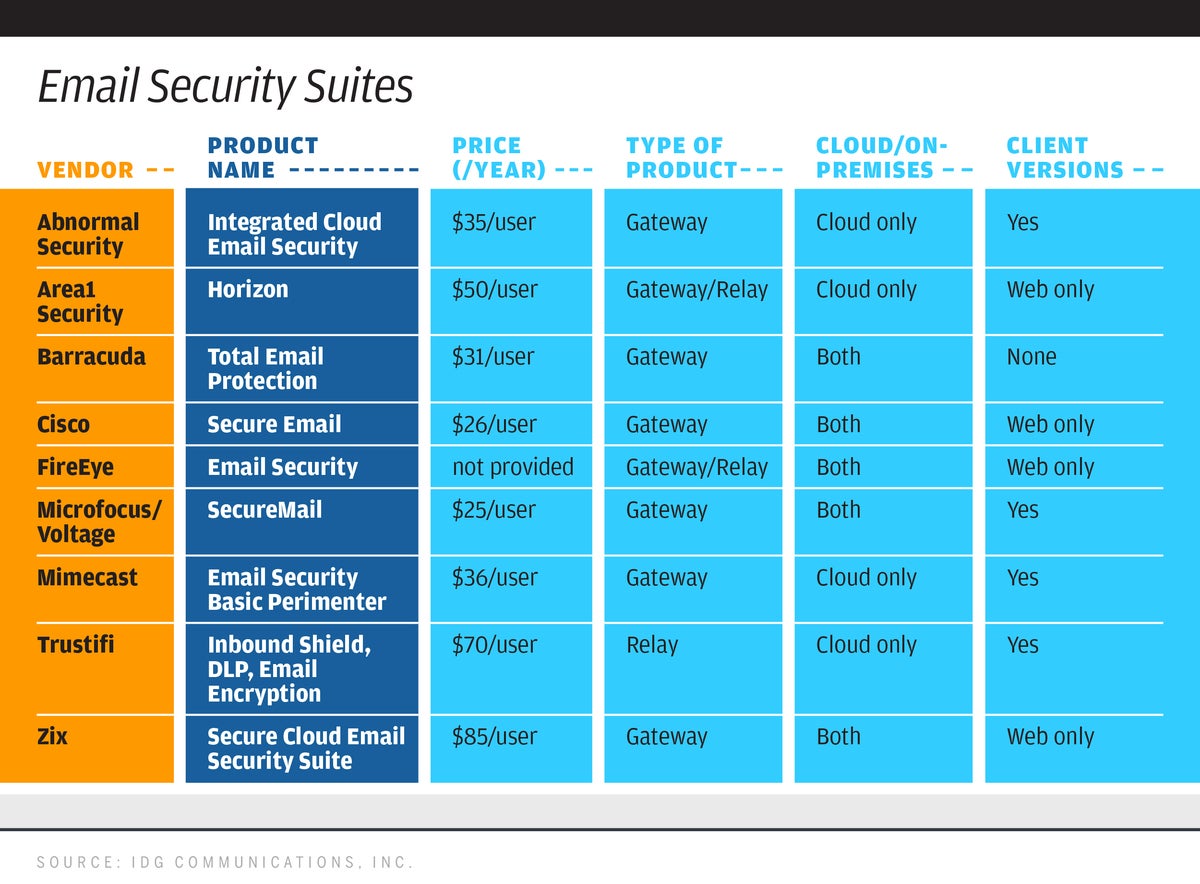

We all know that phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunity for hackers to enter our networks. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking, data leakages or privilege escalation exploits. Over the years a number of security protocols have been invented to try to reduce these opportunities. This is especially needed today, as more of us are working from home and need all the email protection we can muster. In my l

We all know that phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunity for hackers to enter our networks. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking, data leakages or privilege escalation exploits. Over the years a number of security protocols have been invented to try to reduce these opportunities. This is especially needed today, as more of us are working from home and need all the email protection we can muster. In my l Paul Gillin and I are old hands at email newsletters. Paul had his own for several years and has produced several for his clients. I currently publish two:

Paul Gillin and I are old hands at email newsletters. Paul had his own for several years and has produced several for his clients. I currently publish two:

If you want to read a more thorough test, check out

If you want to read a more thorough test, check out