The past week has seen a lot of news stories about hacking our elections. Today I take a careful look at what we know and the various security implications, which I cover in the last paragraph. It is hard to write about this without getting into politics, but I will try to summarize the facts. Here are two of them:

— Russians have tried to penetrate election authorities in every statehouse but weren’t successful — other than Illinois at being able to compromise those networks. We have evidence that has been published in the Mueller report and more recently the Senate Intelligence Committee report from last week.

— A second and more troublesome collection of potential election compromises is described in a report from the San Mateo County grand jury that was also posted last week. I will get to this report in a moment.

For infosec professionals, the events described in these documents have been well known for many years. The reports talk about spear-phishing attacks on election officials, phony posts on social media or posts that originate from sock puppet organizations (such as Russian state-sponsored intelligence agencies), or from consultants to political campaigns that misrepresent themselves to influence an election.

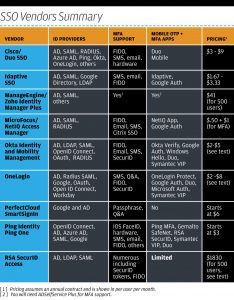

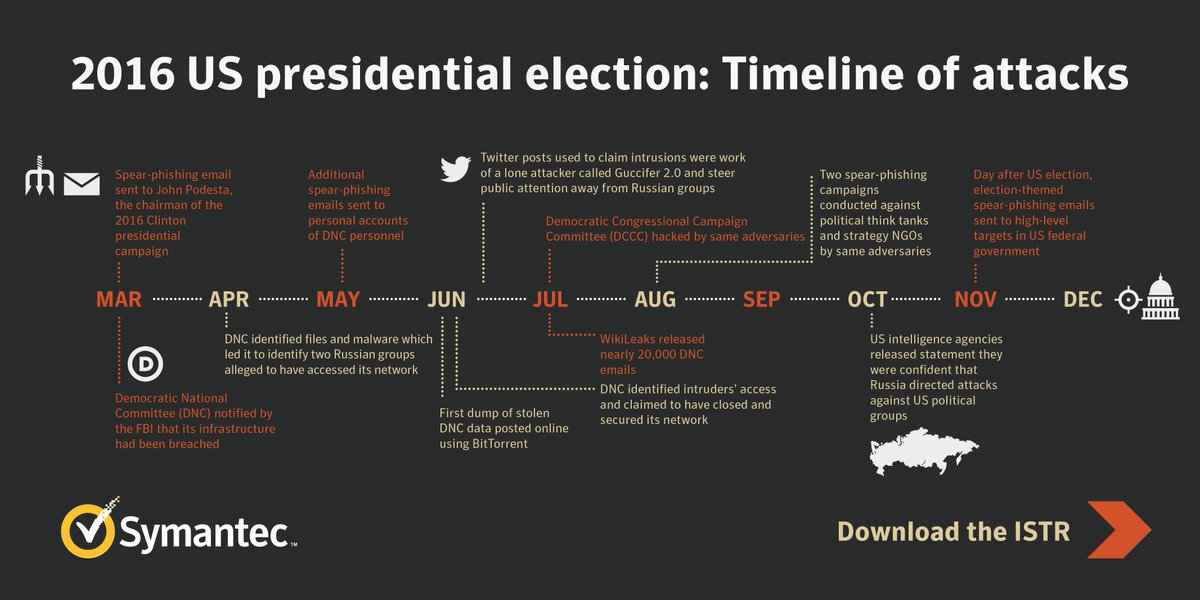

Much of this has already been published, including this timeline infographic from Symantec.

Much of this has already been published, including this timeline infographic from Symantec.

What is new though has little to do with technology failures and more to do with how we have structured our communications and threat sharing data. The Senate report says, “often election experts, national security experts, and cybersecurity experts are speaking different languages. Election officials focus on transparent processes and open access and are concerned about introducing uncertainty into the system; national security professionals tend to see the threat first. Both sides need to listen to each other better and to use more precise language.” The report goes on to document the security failings of 21 state election boards’ operations.

One of the issues has to do with the poor security surrounding electronic voting machines. As I said, this is a well-known problem. A University of Michigan computer science professor has been studying this for years. He purchased some of these machines on eBay and set up a demonstration of how easy it was to hack the votes. Digital voting can be solved, but not easily: Estonia has been voting electronically for years because every Estonian has a digital ID card that isn’t easily hacked. (You can read my experiences with using it here – non-residents can buy one but obviously can’t vote.) You can read more about Estonia’s experience with its online voting here. It shows that digital voting doesn’t increase the overall voting population, but has become more popular since its introduction.

What the Senate report doesn’t document is what has been done since it began its research several years ago. That is the purview of the San Mateo grand jury report which posits that social media accounts of county officials — both their personal accounts as well as their official business accounts — have been compromised in the past and could be used to disrupt elections. These accounts could be used to spread false information both before and after an election. This report is quite chilling and Brian Krebs has a lot more to say about it.

Let’s talk a little more about what the state and local election agencies are doing to better secure our elections. To understand how these agencies are trying to improve their security postures, you have to follow the money.

Several years ago, Congress appropriated $380 million for state grants to improve election security. All of this money hasn’t yet been spent, although it has been allocated to the states and you can see where it is eventually going here in a very confusing report from a federal entity called the U.S. Elections Assistance Commission (EAC). The EAC is in charge of distributing these funds. A better analysis from Pacific Standard can be found in this piece. The state election authorities must match five percent of their grants and spend it all before 2023. Most of these funds are being spent on phishing awareness education, doing regular patching and system updates, and according to this report from last year, “ensuring election results have auditable paper trails, have better built-in cyber defenses and can continue to operate resiliently after a digital attack.” Illinois, Wisconsin and New York are planning to dedicate all of these funding allotments to improving cybersecurity measures. The others have proposed a mix of cyber and non-cyber improvements.

The EAC also provides a collection of various tools and best practices for state and local elections authorities, and you might want to spend some time, as I did, visiting its website and seeing the quality of its advice. On the whole, it is sound, but the problem is getting the hundreds of local officials to act on it and to work together with the feds.

One of these tools is an open-source intrusion detection system called Albert that was first developed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security several years ago and based on Suricata IDS project. This tool has replaced Snort and has become very popular in the commercial IDS world.

States can freely implement this tool and EAC will help them with security monitoring too. This is done with an operations center that houses both one for network-level events called the Multi-state Information Sharing and Analysis Center and one for election security events. It is run by the Center for Internet Security out of an office near Albany NY. Albert sensors are now monitoring election systems that will account for 100 percent of votes to be cast in the 2020 elections. In 2016, it was only covering a third of the votes cast.

Let’s turn from elections operations to influencing how we cast our votes. For that, I will talk about a new Netflix documentary called “The Great Hack,” which is now on its streaming service. I urge you to watch it with your whole family. It mostly follows two people that you might not have heard of and their role in the Cambridge Analytica/Facebook scandal: Brittany Kaiser, a former CA employee and David Carroll, a college professor who tried to sue the company to gain access to his own data. If you can get past the annoying CGI opening credits, there is actually much meat to be gleaned here. The main thesis of the movie has to do with convincing a class of voters it calls the persuadables in swing districts to vote for a particular candidate, or not vote at all. If you don’t have time to watch the movie, you can get the main points from a TED talk by Carole Cadwalladr, one of the reporters featured in the film. Facebook knew about the abuses of its data collection and was fined by the U.S. government last week. (This article by Techcrunch summarizes these details.) Also, in last week’s news: Facebook agreed to pay two fines. First was a $5 billion fine to the Federal Trade Commission, and a second $100 million fine from the Securities and Exchange Commission, which was overshadowed but represents a more important penalty.

OK, that is a lot to grok, I admit. If you have made it this far, here are some action items for you as an individual. First, if you want to vote intelligently, consume social media carefully. Don’t repost without extreme vetting of the source; better yet, go to listen-only mode and steer clear of using social media entirely for politics. I realize that is a lot to ask. Some of you have already abandoned social media entirely. Others have selectively blocked friends who wax too often on political topics. Second, when you vote, if you can use a paper ballot do so, at least until the electronic machines have better protection. Finally, check the election security operations center website to see if your county or city elections authority is a member, and if not, urge them to join.

We’re joined by

We’re joined by  Much of this has already been published, including this timeline

Much of this has already been published, including this timeline