A solid toolset is at the core of any successful digital forensics program, an earlier article that I wrote for CSOonline. Although every toolset is different depending on an organization’s needs, some categories should be in all forensics toolkits. In this roundup for CSOonline, I describe some of the more popular tools, many of which are free to download. I have partitioned them into five categories: overall analysis suites (such as the SANS workstation shown here), disk imagers, live CDs, network analysis tools, e-discovery and specialized tools for email and mobile analysis.

A solid toolset is at the core of any successful digital forensics program, an earlier article that I wrote for CSOonline. Although every toolset is different depending on an organization’s needs, some categories should be in all forensics toolkits. In this roundup for CSOonline, I describe some of the more popular tools, many of which are free to download. I have partitioned them into five categories: overall analysis suites (such as the SANS workstation shown here), disk imagers, live CDs, network analysis tools, e-discovery and specialized tools for email and mobile analysis.

The dangers of DreamHost and Go Daddy hosting

If you host your website on GoDaddy, DreamHost, Bluehost, HostGator, OVH or iPage, this blog post is for you. Chances are your site icould be vulnerable to a potential bug or has been purposely infected with something that you probably didn’t know about. Given that millions of websites are involved, this is a moderate big deal.

It used to be that finding a hosting provider was a matter of price and reliability. Now you have to check to see if the vendor actually knows what they are doing. In the past couple of days, I have seen stories such as this one about GoDaddy’s web hosting:

And then there is this post, which talks about the other hosting vendors:

Let’s take them one at a time. The GoDaddy issue has to do with their Real User Metrics module. This is used to track traffic to your site. In theory it is a good idea: who doesn’t like more metrics? However, the researcher Igor Kromin, who wrote the post, found the JavaScript module that is used by GoDaddy is so poorly written that it slowed down his site’s performance measurably. Before he published his findings, all GoDaddy hosting customers had these metrics enabled by default. Now they have turned it off by default and are looking at future improvements. Score one for progress.

Why is this a big deal? Supply-chain attacks happen all the time by inserting small snippets of JavaScript code on your pages. It is hard enough to find their origins as it is, without having your hosting provider to add any additional burdens as part of their services. I wrote about this issue here.

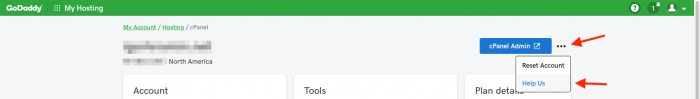

If you use GoDaddy hosting, you should go to your cPanel hosting portal, click on the small three dots at the top of the page (as shown above), click “help us” and ensure you have opted out.

If you use GoDaddy hosting, you should go to your cPanel hosting portal, click on the small three dots at the top of the page (as shown above), click “help us” and ensure you have opted out.

Okay, moving on to the second article, about other hosting provider scripting vulnerabilities. Paulos Yibelo looked at several providers and found multiple issues that differed among them. The issues involved cross-site scripting, cross-site request forgery, man-in-the-middle problems, potential account takeovers and bypass attack vulnerabilities. The list is depressingly long, and Yibelo’s descriptions show each provider’s problems. “All of them are easily hacked,” he wrote. But what was more instructive was the responses he got from each hosting vendor. He also mentions that Bluehost terminated his account, presumably because they saw he was up to no good. “Good job, but a little too late,” he wrote.

Most of the providers were very responsive when reporters contacted them and said these issues have now been fixed. OVH hasn’t yet responded.

So the moral of the story? Don’t assume your provider knows everything, or even anything, about hosting your site, and be on the lookout for similar research. Find a smaller provider that can give you better customer service (I have been using EMWD.com for years and can’t recommend them enough). If you don’t know what some of these scripting attacks are or how they work, go on over to OWASP.org and educate yourself about their basics.

Social media and charitable giving: my own philosophy

It seems as if my email and social media feeds have been filled with fundraising requests ever since Thanksgiving. As these requests pile up, I have been thinking about my own charitable giving policies and how they have evolved over the years.

The spread of social media has provided a ready-made pathway for asking our “friends” for money — and tor them to return the favor. Back in the day when MySpace was the main social network, fundraising was conducted by individual emails or even letters in the mail. Now, thanks to Facebook (and other sties such as Causes and GoFundMe) it is very easy to set up your own personal campaign and you too can be asking your friends for money. In one way, that is progress: we should encourage more philanthropy and provide help to others when we can.

But the proliferation of sites has raised problems for us all: To which cause do we contribute? How can we be sure that a personal appeal in a GoFundMe campaign is legitimate? What do we really know about the causes we are being asked to support?

I confess that this tsunami of appeals causes me internal conflict. I want to be a good person, but my resources of money and time to sort out many requests are both limited.

I asked two of my friends how they sort out these person-to-person (p2p) requests they receive:

- Sarah, a non-profit CEO, told me “If the request doesn’t really speak to me, or I feel like it isn’t really an urgent need, I pass it over. If I see it as making a difference, I usually try to support it in some way. I typically make my decisions based on how well I know the person, or the specific need for the campaign. If it directly helps someone who has experienced a crisis or has a critical need, I am more inclined to give and at a more significant level.”

- Kitty, a development director, contributed to her high school friend’s medical bills as he was dying of cancer. “I did this so his wife, whom I’ve never met, wouldn’t be burdened with these bills after he was gone.” She told me that she was generous with her donation because of the personal connection, even though the connection was established long ago.

For myself, I draw on my upbringing. When I was a teen, I learned about the Talmudic sage Maimonides and his concept about having eight different levels of charity. The highest levels have to do with what I will call double-blind giving: you don’t know the beneficiary, and they don’t know you are the specific donor. The modern style of p2p giving would be very far down Maimonides’ list.

For many years, my own charitable giving has tried to adhere to the Maimonides model. Almost 20 years ago, I decided to get involved in raising funds for curing various diseases: Juvenile Diabetes, AIDS, cancer, and Multiple Sclerosis. I knew friends and family members who suffered from them and that connection caused me to want to help. I ended up doing an annual bike or walkathon and using my contacts – namely those of you who are reading these missives – to raise money. And thanks to you, for many years I have often been very successful in providing meaningful support for these causes.

Then in 2002, I broke my shoulder training for a ride a month before an event. When I called the organizers, they told me to come to Death Valley (where the event was taking place) anyway: they wanted me to participate, even though I wasn’t going to be able to ride. I was glad I did, because my now wife Shirley (shown here at the JDRF finish line) was also a volunteer for the event, and that is where we met.

Then in 2002, I broke my shoulder training for a ride a month before an event. When I called the organizers, they told me to come to Death Valley (where the event was taking place) anyway: they wanted me to participate, even though I wasn’t going to be able to ride. I was glad I did, because my now wife Shirley (shown here at the JDRF finish line) was also a volunteer for the event, and that is where we met.

I was deeply moved that when I told the people who had made pledges to support the ride that I was not able to participate, virtually everyone said that their support was for the cause, not my individual participation, and they wanted to make the contribution in spite of my injury. That is truly the spirit of philanthropy that inspires me and that inspires you as well.

I asked several of my readers to their reactions to an early draft of this column. “An explanation of why and what you are riding helps me in my decision to give you funds,” said one. “I grew up in a time when asking for donation was an in-person activity,” said another. “Nowadays, we have no sense of community. Instead, these p2p donations have become nothing more than feel-good tax deduction trading.” Another supporter said she gives to my causes because I am doing something (the ride or the walk) in addition to “the ask.” And one reader said he is suffering from “donation fatigue,” even though he tries to give up to 10% of his income every month to various causes. And another wonders when did this public begging become so acceptable? She thinks we are taking a step backwards.

So, with that background, I will continue asking from time to time where I believe in the cause. I will happily consider requests where a broad-based benefit is the object of the giving. Together, each of us choosing our own causes, we can make a real difference.

You are welcome to share your own charitable giving philosophies with me or my readers.

FIR B2B podcast #112: What it means to be true to your brand

Welcome to the new year and we hope you all have had a nice holiday break. In today’s episode, Paul Gillin and I talk about what it means to be true to your brand and why marketing managers need to pay more attention than ever to branding in an age in which customers increasingly control the message.

What makes a brand? First off is understanding what are your core values and what lies at the heart of your business. This post for B2B Marketing tells how Burberry, the British clothing maker, literally torched its merchandise in an effort to sustain its premium pricing, a move that turned out to be a major faux Other prominent examples of companies whose bad actions have undermined their brand are Uber and Facebook.

Will brands without social purpose thrive? A new survey finds that two-thirds of consumers expect companies to create products and services that “take a stand” on issues that they also feel passionate about. A great case study can be found in, of all places, with a new British bank called Monzo. It’s trying a new approach to gain customers: raise funds via crowdfunding, open its API, run meetups and hackathons and become more transparent about trying to attract millennial as its customers. Regardless of whether it’s successful, you have to give Monzo credit for originality.

Will brands without social purpose thrive? A new survey finds that two-thirds of consumers expect companies to create products and services that “take a stand” on issues that they also feel passionate about. A great case study can be found in, of all places, with a new British bank called Monzo. It’s trying a new approach to gain customers: raise funds via crowdfunding, open its API, run meetups and hackathons and become more transparent about trying to attract millennial as its customers. Regardless of whether it’s successful, you have to give Monzo credit for originality.

Finally, we offer up a few suggestions on how you can stay true to your brand using storytelling and social media techniques. You can listen to our podcast here:

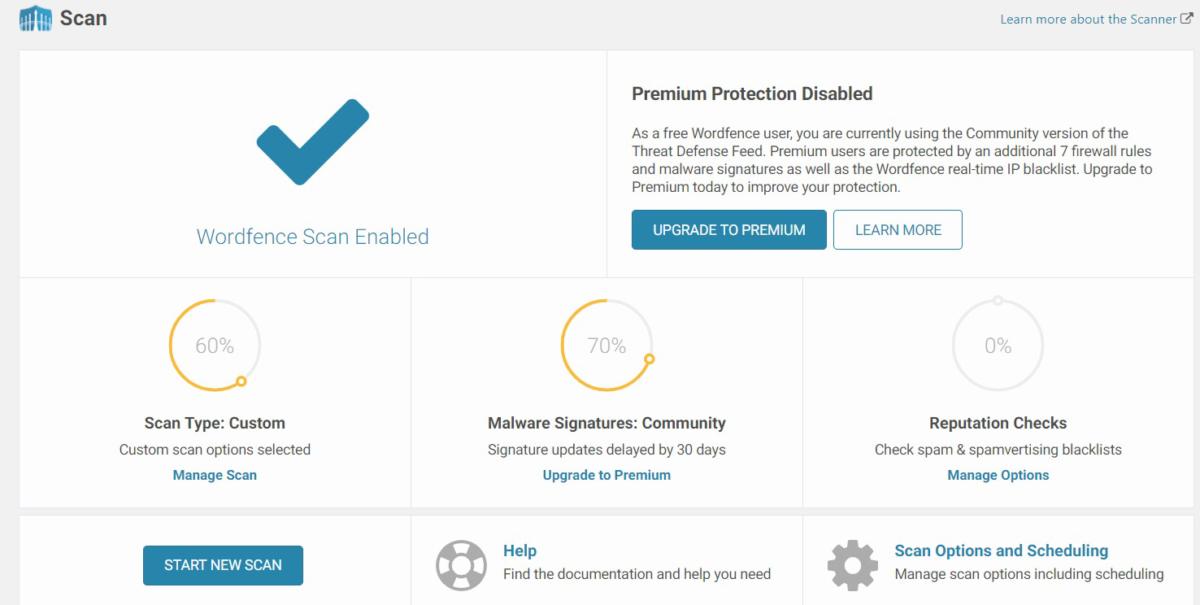

CSOonline: How to secure your WordPress site

If you run a WordPress blog, you need to get serious about keeping it as secure as possible. WordPress is a very attractive target for hackers for several reasons that I’ll get to in a moment. To help you, I have put together my recommendations for the best ways to secure your site, and many of them won’t cost you much beyond your time to configure them properly. My concern for WordPress security isn’t general paranoia; my own website has been attacked on numerous occasions, including a series of DDoS attacks on Christmas day. I describe how to deploy various tools such as WordFence, shown below and you can read more on CSOonline.

Helm Email Server: secure and stylish, but has issues

I had an opportunity to test drive the Helm personal email server over the past couple of months. I give them an A for effort, and a C+ for execution. It is a smallish pyramid that can be used to self-host your own email domain.

It has some great ideas and tries hard to be a secure email server that is easy to setup. And its packaging and reviewer’s guide is a design delight, as you can see from the photo below. But it has a few major drawbacks, especially for users that want to do more than protect their email correspondence.

If you want to read a more thorough test, check out Lee Hutchinson’s Ars review here. While I didn’t test it as thoroughly or write about it as much as he did, I did try it out in two different modes: first, as a server on a test account that Helm reserved for me. Then I reset the unit and tried it to serve up email on one of my existing domains. I will get to an issue with that latter configuration in a moment.

If you want to read a more thorough test, check out Lee Hutchinson’s Ars review here. While I didn’t test it as thoroughly or write about it as much as he did, I did try it out in two different modes: first, as a server on a test account that Helm reserved for me. Then I reset the unit and tried it to serve up email on one of my existing domains. I will get to an issue with that latter configuration in a moment.

My biggest issue is its lack of support for webmail clients. I understand why this was done, but I still don’t like it. I have been using webmail exclusively for my desktop and laptop email usage for more than 10 years, and only use the iPhone Mail app when I am on the phone. Certainly, that leaves me open for exposure, man-in-the-middle, etc. But I am not sure I am willing to give up that flexibility for better security, which is really at the center of the debate.

Brian Krebs blogged that users can pick two of security, privacy and convenience, but only two. That is the rub.

If you are concerned about privacy first and foremost, you are likely to want to use encryption on all of your emails. That is probably for very few folks. Even with zero-trust encryption, this isn’t easy. Helm doesn’t support any encryption such as PGP, so this audience is off the table.

If you are concerned with convenience, you are probably going to stick with webmailers for the time being. So this audience is off the table too.

If you are concerned with security first, maybe you will consider Helm. But it is a big maybe. If you already use a corporate email server and your company has hundreds of mailboxes, I don’t think any IT manager is going to want to have a tiny box like Helm at the center of their email infrastructure. And if you are a SMB that has < 100 mailboxes, perhaps you might move from GSuite or O365, but it will take some work. Certainly, the pricing tipping point is around a dozen mailboxes, depending on the various options that you choose for these SaaS emailers.

Hutchinson’s piece in Ars says, “Helm aims to give you the best of both worlds—the assurance of having a device filled with sensitive information physically under your control, but with almost all of the heavy sysadmin lifting done for you. If you’re looking to kick Google or Microsoft to the curb and claw back control of your email, this is in my opinion the best and easiest way to do it.” I would agree with him.

However, the issue for this last group isn’t the email, but the other things that depend on email that they already use seamlessly: calendars, contacts, and email notifications. Setting up calendars and contacts will take some careful study before you actually configure them. This is because you have to read and understand the web-based support portal pages so that you know what the steps are before you do the configuration. I ended up creating several device profiles before I got all this together, because I couldn’t access the existing details to set up the servers etc. (I understand why you are doing this, but still calling them “device profiles” is confusing.) And then I still had issues with getting things setup for my calendar and contacts. The pretty reviewer’s guide really falls down in this area.

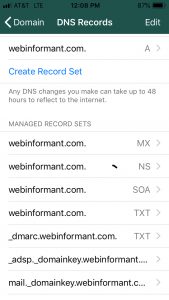

One plus for the security audience is that it supports DMARC/SPF/DKIM with no extra effort. (See the screenshot below.) They don’t make a big deal of this, other than a brief nod to it in the support pages here. My report from mail-tester can be found here, showing that this was implemented correctly.

Another sticking point for me is the use of the smartphone app for configuration and reporting. I have had problems with other consumer-grade products that do this – such as most smart home devices, the Bitdefender Box (I did an early review of this for Tom’s Hardware but haven’t looked at it for a while since then), and some SMB router/firewalls. The problem is that your screen real estate is very limited, forcing you to make some bad UI tradeoffs. For example, a notification alert comes up on my phone during certain times.

One issue that Hutchinson also had is that if you use Helm to serve up your own domain, it needs to take control over your domain’s DNS settings. You can use its smartphone app to add your own custom DNS records, but it isn’t as flexible as say the average ISP DNS web-based management screens. Speaking of DNS, Helm doesn’t support DNSSEC because of the way it moves your email traffic through its AWS infrastructure.

Finally, the backup process didn’t work for my pre-configured unit and I never got a successful backup, even after initiating several of them. It worked fine for my hosted domain. There is no phone message notification of either success or failure: you have to check the app, which also seems like a major omission.

If you aren’t happy with the security implications of Microsoft/Googleplex owning your messages and are a small business that doesn’t use much webmail, then Helm should be a great solution. It costs $500 initially, with $100 annually for a support contract.

Both real and fake Facebook privacy news

I hope you all had a nice break for the holidays and you are back at work refreshed and ready to go. Certainly, last year hasn’t been the best for Facebook and its disregard for its users’ privacy. But a post that I have lately seen come across my social news feed is blaming them for something that isn’t possible. In other words, it is a hoax. The message goes something like this:

Deadline tomorrow! Everything you’ve ever posted becomes public from tomorrow. Even messages that have been deleted or the photos not allowed. Channel 13 News talked about the change in Facebook’s privacy policy….

Snopes describes this phony alert here. They say it has been going on for years. And it has gained new life, particularly as the issues surrounding Facebook privacy abuses have increased. So if you see this message from one of your Facebook friends, tell them it is a hoax and nip this in the bud now. You’re welcome.

Snopes describes this phony alert here. They say it has been going on for years. And it has gained new life, particularly as the issues surrounding Facebook privacy abuses have increased. So if you see this message from one of your Facebook friends, tell them it is a hoax and nip this in the bud now. You’re welcome.

The phony privacy message could have been motivated by the fact that many of you are contemplating leaving or at least going dark on your social media accounts. Last month saw the departure of several well known thought leaders from the social network, such as Walt Mossberg. I am sure more will follow. As I wrote about this topic last year, I suggested that at the very minimum if you are concerned about your privacy you should at least delete the Facebook Messenger app from your phone and just use the web version.

But even if you leave the premises, it may not be enough to completely cleanse yourself of anything Facebook. This is because of a new research report from Privacy International that is sadly very true. The issue has to do with third-party apps that are constructed from Facebook’s Business Tools. And right now, it seems only Android apps are at issue.

The problem has to do with the APIs that are part of these tools, and how they are used by developers. One of the interfaces specifies a unique user ID value that is assigned to a particular phone or tablet. That ID comes from Google, and is used to track what kind of ads are served up to your phone. This ID is very useful, because it means that different Android apps that are using these Facebook tools all reference the same number. What does this mean for you? Unfortunately, it isn’t good news.

The PI report looked at several different apps, including Dropbox, Shazam, TripAdvisor, Yelp and several others.

If you run multiple apps that have been developed with these Facebook tools, with the right amount of scrutiny your habits can be tracked and it is possible that you could be un-anonymized and identified by the apps you have installed on your phone. That is bad enough, but the PI researchers also found out four additional disturbing things to make matters worse:

First, the tracking ID is created whether you have a Facebook account or not. So even if you have gone full Mossberg and deleted everything, you will still be tracked by Facebook’s computers. It also is created whether your phone is logged into your Facebook account (or using other Facebook-owned products, such as What’sApp) or not.

Second, the tracking ID is created regardless of what you have specified for your privacy settings for each of the third-party apps. The researchers found that the default setting by the Facebook developers for these apps was to automatically transfer data to Facebook whenever a phone’s user opens the app. I say was because Facebook added a “delay” feature to comply with the EU’s GDPR. An app developer has to rebuild their apps with the latest version to employ this feature however. The PI researchers found 61% of the apps they tested automatically send data when they are opened.

Third, some of these third-party apps send a great deal of data to Facebook by design. For example, the Kayak flight search and pricing tool collects a great deal of information about your upcoming travels – this is because it is helping you search for the cheapest or most convenient flights. This data could be used to construct the details about your movements, should a stalker or a criminal wish to target you.

When you put together the tracking ID with some of this collected data, you can find out a lot about whom you are and what you are doing. The PI researchers, for example, found this one user who was running the following apps:

- “Qibla Connect” (a Muslim prayer app),

- “Period Tracker Clue,”

- “Indeed” (a job search app), and

- “My Talking Tom” (a children’s’ app).

This means the user could be potentially profiled as likely a Muslim mother who is looking for a new job. Thinking about this sends a chill up my spine, as it probably does with you. The PI report says, “Our findings also show how routinely and widely users’ Google ad ID is being shared with third parties like Facebook, making it a useful unique identifier that enables third parties to match and link data about an individual’s behavior.”

Finally, the researchers also found that the opt-out methods don’t do anything; the apps continue to share data with Facebook no matter what you have done in your privacy settings, or if you have explicitly sent any opt-out messages to the app’s creators.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of apps that exhibit this behavior: researchers found that Facebook apps are the second most popular tracker, after Google’s parent company Alphabet, for all free apps on the Google Play Store.

So what should you do if you own an Android device? PI has several suggestions:

First, reset your advertising ID regularly by going to Settings > Google > Ads > Reset Advertising ID. Next, go to Settings > Google > Ads > Opt out of personalized advertising to limit these types of ads that leverage your personal data. Next, make sure you update your apps to keep them current. Finally, regularly review the app permissions on your phone and make sure you haven’t granted them anything you aren’t comfortable doing.

Clearly, the real bad news about Facebook is stranger than fiction.

iBoss blog

I wrote for them from 2016-2018. They have removed most of these articles, contact me if you want any copies of them.

- We still have plenty of network printer attacks (3/18)

- A tour of current blockchain exploits (2/18)

- Ten ways to harden WordPress (2/18)

- The year of vulnerabilities in review (12/17)

- What is HTTP Strict Transport Security? (12/17)

- How to cope with malicious PowerShell exploits (10/17)

- How to secure containers (10/17)

- Implementing better email authentication systems (10/17)

- What is WAP billing and how is it being exploited? (9/17)

- The difference between anonymity and privacy (9/17)

- What is OAuth and why should I care? (8/17)

- The dark side of SSL certificates (8/17)

- What is the CVE and why is it important (8/17)

- Why you need to deploy IPv6 (7/17)

- Three-part series on the new rules of MFA (7/17)

- What is fileless malware? (6/17)

- How ransomware is changing the nature of customer service (6/17)

- WannaCry: Where do we go from here? (5/17)

- What is a booter and a stressor? (12/16)

- The challenges and opportunities for managing IoT (12/16)

- Who are the bug bounty hunters (11/16)

- How to heighten HIPAA security (10/16)

- Why grammar counts in decoding phished emails (10/16)

- How to communicate to your employees after a breach (9/16)

- 6 Lessons Learned from the US Secret Service on How to Protect Your Enterprise (9/16)

- Economist paints a dark future for banking industry (8/16)

- Wireless keyboards vulnerable to hacking (8/16)

- Hacking Your Network Through Smart Light Bulbs (8/16)

- Windows 10 Anniversary security features: worth the upgrade (8/16)

- How to implement the right BYOD program (8/16)

- The benefits and risks of moving to BYOD (8/16)

- There is no single magic bullet for IoT protection (7/16)

- Beware of wearables (7/16)

- Understanding the keys to writing successful ransomware ((7/16)

- It’s Time to Improve Your Password Collection (6/16)

- Euro banking cloud misperceptions abound (6/16)

- Beware of ransomware as a service (6/16)

- When geolocation goes south (5/16)

- Turning the tide on polymorphic malware (5/16)

- How stronger authentication can better secure your cloud (4/16)

- The Internet-connected printer can be another insider threat (4/16)

- Beware of malware stealing credentials (4/16)

FIR B2B podcast episode #111: Why marketers should care about privacy invasion

Perhaps the most important B2B marketing story of 2018 is the invasion of our privacy. In our final podcast of the year, Paul Gillin and I talk about how companies have been so cavalier in abusing the data that their customers give them. This invasion has happened through a combination of several circumstances:

- In the case of Facebook’s failures, the combination of a lack of transparency and an immature and misguided management team.

- In the case of Google,not being truthful about what its incognito browsing mode is actually doing and how it is doing it. This is from a report from one of Google’s competitors, DuckDuckGo, which found that Chrome personalizes search results even when users aren’t signed in.

- Abusing smartphone app permissions, as a new study by the New York Times revealed this week. Apps were tracking users’ movements and despite claims that identifying information had been removed, the Times reporters were able to track down a few users and interview them for the story. How they did their research is a fascinating look at how difficult one’s privacy can be to protect today.

Certainly, next year is shaping up to be a watershed moment in resolving these micro-targeting issues and being more parsimonious in how our data privacy is protected. We welcome your thoughts on the matter, along with a few suggestions for marketers to better audit what their developers are doing with respect to privacy. You can listen to our 15 min. episode below. Have a happy and healthy holidays and a great new year!

Certainly, next year is shaping up to be a watershed moment in resolving these micro-targeting issues and being more parsimonious in how our data privacy is protected. We welcome your thoughts on the matter, along with a few suggestions for marketers to better audit what their developers are doing with respect to privacy. You can listen to our 15 min. episode below. Have a happy and healthy holidays and a great new year!

Screencast review: Managing enterprise mobile device security with Zimperium

Zimperium is very useful in finding mobile device risks and fixing security issues across the largest enterprise networks.

It includes phishing detection and has the ability to run on both a variety of different cloud infrastructures as well as on-premises. It has deep on-device detection and a fine-grained collection of access roles. It uses a web-based console that controls protection policies and configuration parameters. Reports can be customized as well for management and compliance purposes. I tested the software in December 2018 on a sample network with both Android and iOS devices of varying vintages and profiles.

Pricing decreases based on volume starting at $60/year/device

Keywords: David Strom, web informant, video screencast, mobile device security, mobile device manager, MDM, mobile threat management, Knox security, iOS security