An article in this week’s New York Times decries the end of the floppy disk. Its use as a medium of data transfer for Japanese government reports has finally been replaced with online data transfer. I read the piece with a mixture of sadness and amusement. The floppy was a big deal — originating from IBM’s big iron. It became the basic fuel of the PC revolution.

Before we had PCs, in the late 1970s, we had the first dedicated word processor machines coming into offices. I came of professional age when these huge beasts, often built-in to office furniture. They were the domain of the typing pool of secretaries that would transform hand-written drafts into typed documents. These word processors had printers and ran off 8″ floppies that held mere kilobytes of text files. Those larger disks were a part of America’s nuclear control bunkers up until 2019 or so.

But back to the 1980s. Then IBM (and to some extent Apple) changed all that with the introduction of 5″ versions that were attached to their PCs. Actually, they measured five and a quarter inches. Within a few years, they became “double-sided” disks, holding a huge 360 KB of files. To give you an idea of this vast quantity of storage, you could save dozens of files on a single disk. But things were moving fast in those early days of the PC — soon we had hard-shell 3.5 inch floppies — the label remained, even though the construction changed — that could hold more than a megabyte of data. Just imagine: today’s smart watches, let alone just about any other smart home device — can hold gigabytes of data.

You would be hard-pressed to find a computing device that has less capacity these days. And that is a good thing, because today’s files — especially video and audio — occupy those gigabytes. But I just checked: a 5,000 MS Word file — just text — is only 35 KB, so things haven’t changed all that much in the text department.

The double-sided label sticks in my mind with this anecdote. The scene was a downtown office in LA, where I worked for the IT department of a large insurance company in the mid-1980s. We occupied three office towers that spanned several blocks, and part of the challenge of being in IT was that you spent a lot of time going around the complex — or at least for the times — debugging user’s problems. We would often tell users to send us a copy of their disk via interoffice mail and we would take a look at it if it wasn’t urgent. Soon after I got this call I got the envelope. Inside were two sheets of paper: the user had placed his floppy disk on the glass bed of their Xerox copier, and sent me the printouts. But this was a user who was paying attention: he noticed the “double-sided” designation on the disk, so flipped it over and made a copy of the back of the disk too.

The dual-floppy drive PC was a staple for many years: one was used to run your software, the other to store your data. The software disks were also copy-protected, which made it hard for IT folks to backup. I remember going over to our head of IT’s home one weekend to try to fix a problem he had with the copy-protected version of Lotus 1-2-3, the defining spreadsheet of the day.

Those were fun times to be in the world of PCs. The scene shifts to downtown Boston, at the offices of PC Week, back in early 1987. I had left the insurance company and taken a job with the publication. A few months into the job, I had gotten a question from a colleague who was having trouble with his PC, the original dual floppy-drive IBM model. I went over to his desk and tried to access his files, only to hear the disk drive grind away — not a sound that you want to hear. I flipped open the drive door and removed the offending disk. My colleague looked on with curiosity. “Those come out?” he exclaimed. No one at the publication had bothered to tell him that was the case, and he had been using the same physical disk for months, erasing and creating files until the plastic was so worn out that you could almost see through it. I showed him our supply cabinet where he could stock up on spare floppies.

Apple was the first company to sell computers sans floppies in 1998, and other PC makers soon eliminated them. Storage on USBs and networks made them obsolete.Sony would stop selling the blank disks in 2011, but they lived on in Japan until now.

Floppies were trouble, to be sure. But they were secure: we didn’t have to worry about our data being transmitted across the world for everyone to see. And while their storage capacity was minuscule — especially by today’s standards — it was sufficient to launch a thousand different companies.

Self-promotions dep’t

Speaking of other things that have lived on in Japan, I recently wrote about the Interop show network and its storied history. I interviewed many of the folks who created and maintained these networks over the years, and why Interop was an innovative show, both then and now.

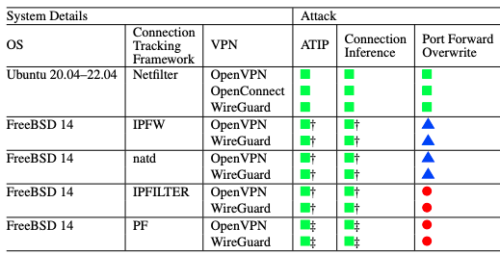

As you can see from the chart below, it goes to the way modern VPNs are designed and depends on Network Address Translation (NAT) and how the VPN software consumes NAT resources to initiate connection requests, allocates IP addresses, and sets up network routes.

As you can see from the chart below, it goes to the way modern VPNs are designed and depends on Network Address Translation (NAT) and how the VPN software consumes NAT resources to initiate connection requests, allocates IP addresses, and sets up network routes. The latest in face fraud has little to do with AI-generated deep fake videos, according to

The latest in face fraud has little to do with AI-generated deep fake videos, according to  Three women nearing 50 share a vacation to celebrate one of them getting divorced. The three share a common tragedy 20-plus years ago involving a grisly mass murder scene in a guesthouse and have since bonded over the experience. This isn’t the most unique plots for a thriller until the bodies start dropping when the vacation turns sour, relationships strain, and the trio meets a mysterious couple of newlyweds. Then things get interesting, and we learn more about the backgrounds of all the parties and try to solve both the original mystery that brought the women together as well as what is happening in the current timeline. One of them puts it quite eloquently when she says she has been listening to the soundtrack of life and she is caught up in her grief over the original grisly murder scene — which somehow she escaped. The characters are finely drawn, and this is the first murder mystery that hinges on an artificial intelligence plot twist which was cleverly conceived.

Three women nearing 50 share a vacation to celebrate one of them getting divorced. The three share a common tragedy 20-plus years ago involving a grisly mass murder scene in a guesthouse and have since bonded over the experience. This isn’t the most unique plots for a thriller until the bodies start dropping when the vacation turns sour, relationships strain, and the trio meets a mysterious couple of newlyweds. Then things get interesting, and we learn more about the backgrounds of all the parties and try to solve both the original mystery that brought the women together as well as what is happening in the current timeline. One of them puts it quite eloquently when she says she has been listening to the soundtrack of life and she is caught up in her grief over the original grisly murder scene — which somehow she escaped. The characters are finely drawn, and this is the first murder mystery that hinges on an artificial intelligence plot twist which was cleverly conceived.  I am of two minds with this novel, which chronicles a fictional Jewish family on the north shore of Long Island and how they devolve after the father is kidnapped for a week. The three children are tracked as they grow up into dysfunctional adults with addiction problems, with marital problems, and with various other issues in trying to cope with their father’s ordeal. The Long Island Compromise is really a devil’s bargain — having lived in one of the wealthiest suburbs in America, after escaping the Holocaust, after dealing with numerous anti-semitic people, places, and circumstances. Having grown up on Long Island’s south shore and raised my daughter on the North Shore in a community that mirrors what is described in fictional terms in the novel, this story resonated with me. The excesses experiences with the family’s wealth, and with trying to out-Jew their neighbors is all too real.

I am of two minds with this novel, which chronicles a fictional Jewish family on the north shore of Long Island and how they devolve after the father is kidnapped for a week. The three children are tracked as they grow up into dysfunctional adults with addiction problems, with marital problems, and with various other issues in trying to cope with their father’s ordeal. The Long Island Compromise is really a devil’s bargain — having lived in one of the wealthiest suburbs in America, after escaping the Holocaust, after dealing with numerous anti-semitic people, places, and circumstances. Having grown up on Long Island’s south shore and raised my daughter on the North Shore in a community that mirrors what is described in fictional terms in the novel, this story resonated with me. The excesses experiences with the family’s wealth, and with trying to out-Jew their neighbors is all too real.