It has been 20 years since Marshall Rose and I wrote our book about Internet email. Since then, it has become almost a redundant term: how could you have email without using the Internet? For that matter, how can you have a business without any email to the outside world? It seems unthinkable today.

It has been 20 years since Marshall Rose and I wrote our book about Internet email. Since then, it has become almost a redundant term: how could you have email without using the Internet? For that matter, how can you have a business without any email to the outside world? It seems unthinkable today.

But for something so essential to modern life, Internet email also comes with multiple ironic situations. I will get to these in a moment.

To do some research for this essay, I re-read a column that I wrote ten years ago about the evolution of email between 1998-2008. Today I want to talk about the last ten years and what we all have been doing during this period. I would call this decade the post email era because email has become the enabling technology for an entire class of applications that previously weren’t possible or weren’t as easy ten years ago. Things like Slack, MFA logins, universal SMS, and the thousands of apps that notify us of their issues using emails. Ironically, all of this has almost eclipsed the actual use of Internet email itself. While ten years ago we had many of these technologies, now they are in more general use. And by post-email I don’t mean that we have stopped using it; quite the contrary. Now it is so embedded in our operations that most of us don’t even think much about it and take it for granted, like the air we breathe. That’s its second irony.

When a new business is being formed, usually the decision for its email provider comes down to hosting email on Google or Microsoft’s servers. That is a big change from ten years ago, when cloud-based email was still being debated and (in some cases) feared. I have been hosting my email on Google’s servers for more than ten years, and many of you have also done the same.

Another change is pricing. This has made email a commodity and it is pretty reasonable: Google charges $5 per month for 30 GB of storage or $10 per month with either 1 TB or unlimited storage. If you want to go with Microsoft, they have similarly priced plans for 1 TB of storage. That is an immense amount of storage. Remember when the first cloud emailers had 1 GB of storage? That seems so quaint — and so limiting — now. For all the talk back then about “inbox zero” (meaning culling messages from your inbox as much as possible), we have enabled email hoarding. That’s another irony.

Apart from all this room to keep our stuff, another major reason for using the cloud is that it frees up the decision as to which email client to run (and to support) for each user. A third reason is that the cloud frees up users to run multiple email clients, depending on what device and for what particular post-email task they want to accomplish. Both of these concepts were pretty radical 20 years ago, and even five years ago they were still not as well accepted as they are now. Today many of us spend more of our time on email with our phones than our desktops, and use multiple programs for our email, and don’t give this a second thought.

Why would anyone want to host their own email server anymore? Here is another irony: one reason is privacy. The biggest thing to happen to email in the past ten years was a growing awareness of how exposed one’s email communications could be. Between Snowden’s revelations and Hillary’s server, it is now crystal clear to the world at large that your email can be read by your government.

When Marshall developed the early email protocols, he didn’t hide this aspect of its operations. It just took the rest of the world many years to catch on. As a result, we now have companies that are deliberating locating in data havens to prevent governments from gaining access to their data streams. Witness ProtonMail and Kolabnow, both doing business from Switzerland, and Mailfence, operating out of Belgium. These companies have picked their locations because they don’t want your email finding its way into the NSA’s Utah data centers, or anywhere else for that matter. And we have articles such as this one in Ars that discuss the issues about Swiss privacy laws. Today a business knows enough to ask where its potential messages will be stored, whether they will be encrypted, and who has control over its encryption keys. That certainly wasn’t in many conversations — or even decisions about selecting an email provider — ten years ago.

One way to take back control over your email is literally to host your own email server so that your message traffic is completely under your control. That has been a difficult proposition even for tech-savvy businesses — until now. This is what Helm is trying to do, and they have put together a sexy little server (about the size of of a small gingerbread house, to keep things festive and seasonal) which can sit on any Internet network anywhere in the world and deliver messages to your inbox. It doesn’t take a lot of technical skill to setup (you use a smartphone app), and it will encrypt all your messages from end-to-end. Helm doesn’t touch them and can’t decrypt them either. Because of this, the one caveat is that you can’t use a webmail client. That is a big tradeoff for many of us that have grown to like webmail over the past decade. Brian Krebs blogged this week that users can pick two items out of security, privacy and convenience. That is the rub. With Helm, you get privacy and security, but not convenience (if you are a webmail user). Irony again: webmail has become so pervasive but you need to go back to running your own server and email desktop clients if you want ironclad security.

Speaking of email encryption, one thing that hasn’t change in the past ten years is how it is rarely used. One of the curiosities of the Snowden revelations was how hard he had to work to find a reporter who was adept enough at using PGP to exchange encrypted messages. Encryption still is hard. And while Protonmail and Tutanova and others (mentioned in this article) have come into play, they are still more curiosities than in widespread general use.

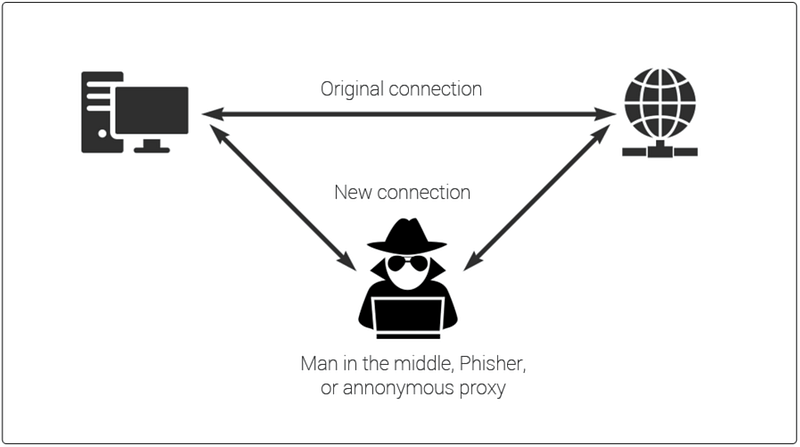

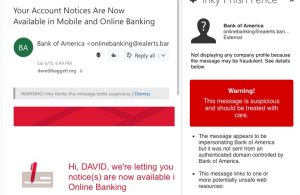

Another trend over the past ten years is how spam and phishing have become bigger problems. This is happening as our endpoints get better at filtering malware out of our inboxes. This is one reason to use hosted Exchange or Gmail: both companies are very good at stopping spam and malicious messages.

It is somewhat of an ironic contradiction: you would hope that better spam processing would make us safer, not more at risk. This risk is easy to explain but hard to prevent. All it takes is just one user on your network, who clicks on one wrong attachment, and a hacker can gain control over your desktop and eventually your entire network. Now that scenario is a common one witnessed in many TV and movie episodes, even in non-sci-fi-themed shows. For example, this summer we had Rihanna as a hacker in Ocean’s 8. Not very realistic, but certainly fun to watch.

It is somewhat of an ironic contradiction: you would hope that better spam processing would make us safer, not more at risk. This risk is easy to explain but hard to prevent. All it takes is just one user on your network, who clicks on one wrong attachment, and a hacker can gain control over your desktop and eventually your entire network. Now that scenario is a common one witnessed in many TV and movie episodes, even in non-sci-fi-themed shows. For example, this summer we had Rihanna as a hacker in Ocean’s 8. Not very realistic, but certainly fun to watch.

So welcome to the many ironies of the post email era. Share your thoughts about how your own email usage has evolved over this past decade if you feel so inclined.

Email is inherently insecure. Sorry, it has been that way since its invention, and still is. All of us don’t give its security the attention it needs and deserves. So if you got one of these messages, or if you are worried about your exposure to a future one, I have a few suggestions.

Email is inherently insecure. Sorry, it has been that way since its invention, and still is. All of us don’t give its security the attention it needs and deserves. So if you got one of these messages, or if you are worried about your exposure to a future one, I have a few suggestions. There were some standout reports that I will recommend. First, if you are new to email encryption, the best general source that I have found is

There were some standout reports that I will recommend. First, if you are new to email encryption, the best general source that I have found is

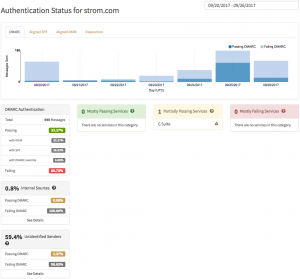

To provide better spam and phishing protection, a number of ways to improve on email message authentication have been available for years, and are being steadily implemented. However, it is a difficult path to make these methods work. Part of the problem is because there are multiple standards and sadly, you need to understand how these different standards interact and complement each other. Ultimately, you are going to need to deploy all of them.

To provide better spam and phishing protection, a number of ways to improve on email message authentication have been available for years, and are being steadily implemented. However, it is a difficult path to make these methods work. Part of the problem is because there are multiple standards and sadly, you need to understand how these different standards interact and complement each other. Ultimately, you are going to need to deploy all of them.

I never thought I would see the day where executives and major public figures would be proud of their techno-luddite status. Scratch that. Not proud, but grateful. In

I never thought I would see the day where executives and major public figures would be proud of their techno-luddite status. Scratch that. Not proud, but grateful. In