We are using our mobile phones for more and more work-related tasks, and the bad guys know this and are getting sneakier about ways to compromise them. One way is to use a third-party keyboard that can be used to capture your keystrokes and send your login info to a criminal that then steals your accounts, your money, and your identity.

What are these third-party keyboards? You can get them for nearly everything – sending cute GIFs and emojis, AI-based text predictors, personalized suggestions, drawing and swiping instead of tapping and even to type in a variety of colored fonts. One of the most popular iOS apps from last year was Bitmoji, which allows you to create an avatar and adds an emoji-laden keyboard. Another popular Android app is Swiftkey. These apps have been downloaded by millions of users, and there are probably hundreds more that are available on the Play and iTunes stores.

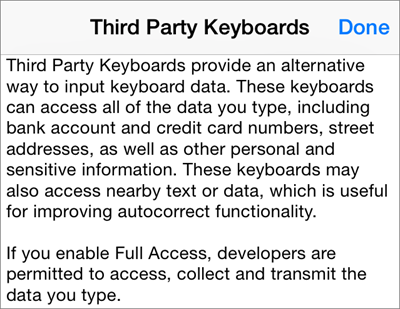

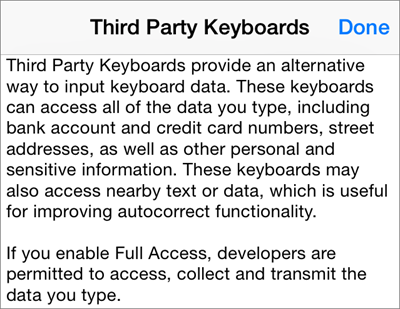

Here is the thing. In order to install one of these keyboard apps, you have to grant it access to your phone. This seems like common sense, but sadly, this also grants the app access to pretty much everything you type, every piece of data on your phone, and every contact of yours too. Apple calls this full access, and they require these keyboards to ask explicitly for this permission after they are installed and before you use them for the first time. Many of us don’t read the fine print and just click yes and go about our merry way.

Here is the thing. In order to install one of these keyboard apps, you have to grant it access to your phone. This seems like common sense, but sadly, this also grants the app access to pretty much everything you type, every piece of data on your phone, and every contact of yours too. Apple calls this full access, and they require these keyboards to ask explicitly for this permission after they are installed and before you use them for the first time. Many of us don’t read the fine print and just click yes and go about our merry way.

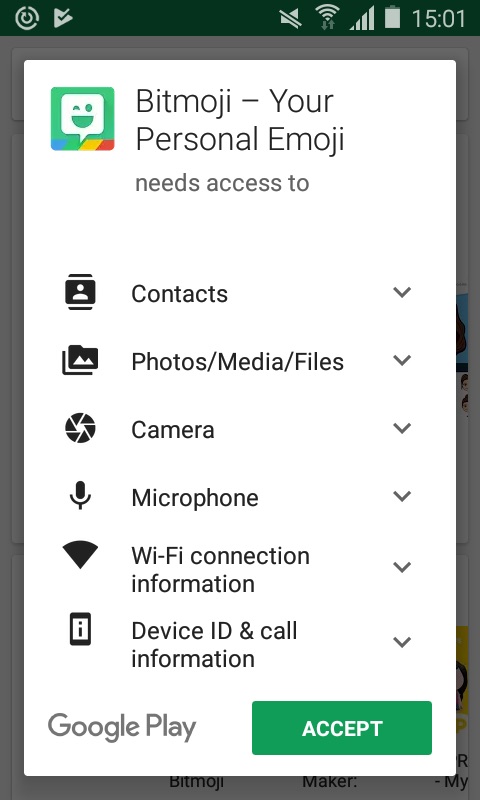

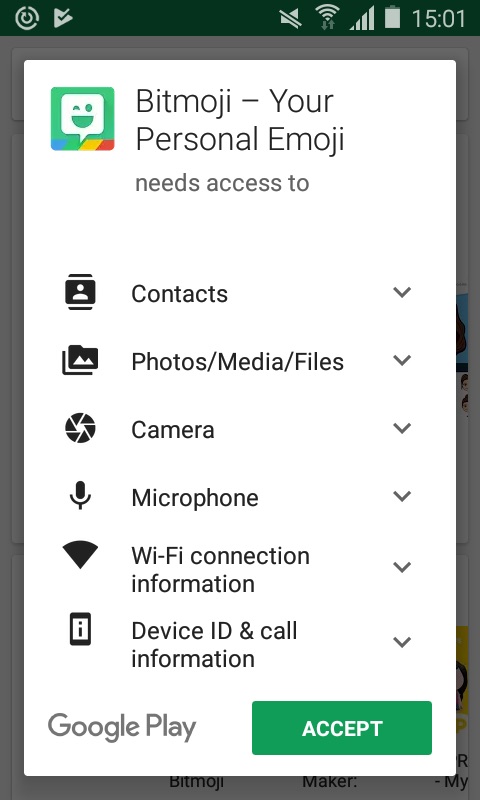

On Android phones, the permissions are a bit more granular, as you can see in this screenshot. This is actually just half of the overall permissions that are required.

On Android phones, the permissions are a bit more granular, as you can see in this screenshot. This is actually just half of the overall permissions that are required.

An analysis of Bitmoji in particular can be found here, and it is illuminating.

Security analysts have known about this problem for quite some time. Back in July 2016, there was an accidental leak of data from millions of users of the ai.type third-party keyboard app. Analyst Lenny Zeltser looked at this leak and examined the privacy disclosures and configurations of several keyboard apps.

So what can you do? First, you probably shouldn’t use these apps, but trying telling that to your average millennial or teen. You can try banning the keyboards across your enterprise, which is what this 2015 post from Synopsys recommends. But many enterprises today no longer control what phones their users purchase or how they are configured.

You could try to educate your users and have them pay more attention to what permissions these apps require. We could try to get keyboard app developers to be more forthcoming about their requirements, and have some sort of trust or seal of approval for those that actually play by the rules and aren’t developing malware, which is what Zeltser suggests. But good luck with either strategy.

We could place our trust in Apple and Google to develop more protective mobile OSs. This is somewhat happening: Apple’s iOS will automatically switch back to the regular keyboard when it senses that you are typing in your user name or password or credit card data.

In the end though, users need to understand the implications of their actions, and particularly the security consequences of installing these keyboard replacement apps. The more paranoid and careful ones among you might want to forgo these apps entirely.

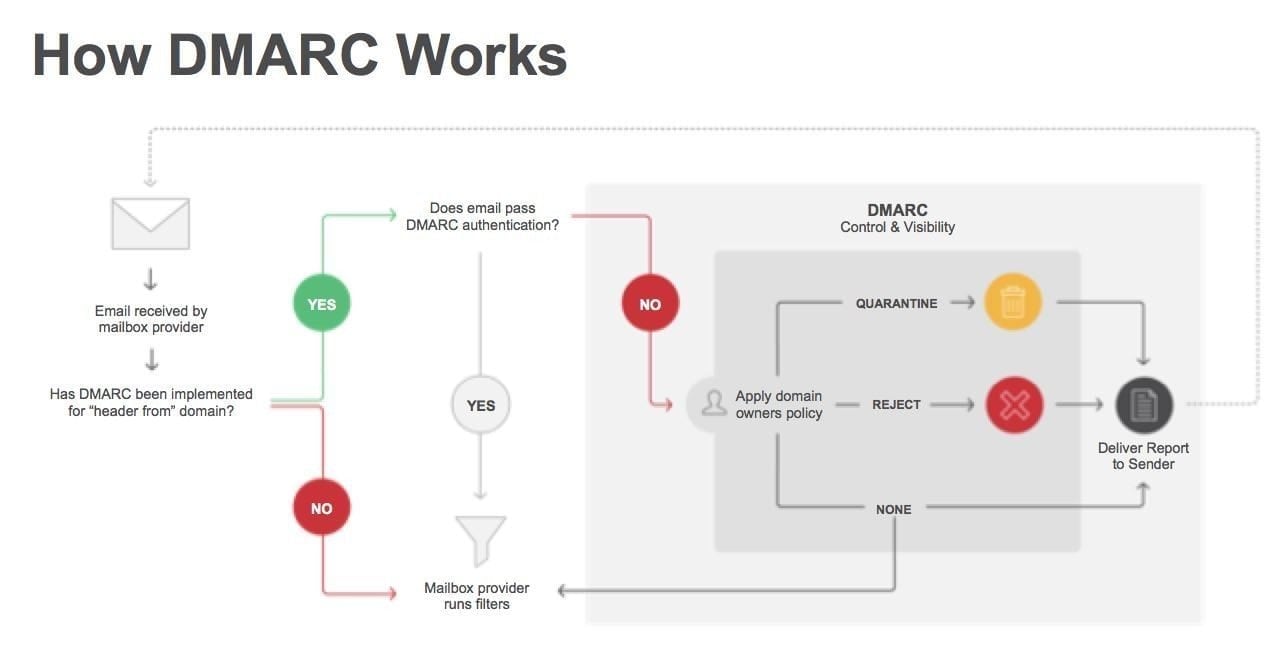

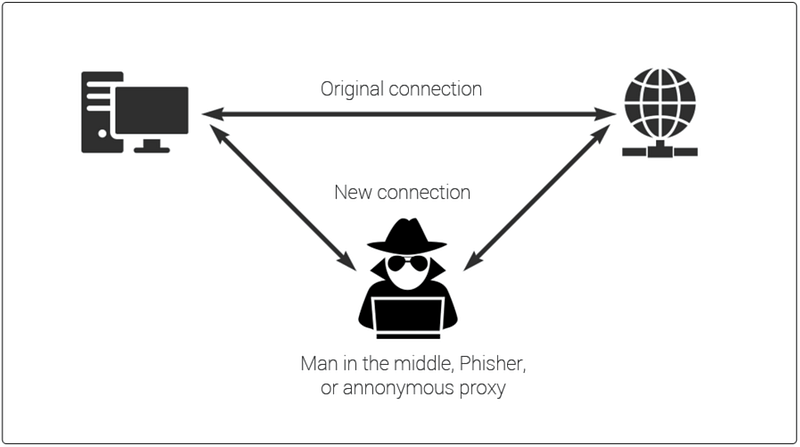

Phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunities for hackers to enter the network. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking scripts, data leakages, or privilege escalation exploits. Despite making some progress, a trio of email security protocols has seen a rocky road of deployment in the past year. Going by their acronyms SPF, DKIM and DMARC, the three are difficult to configure and require careful study to understand how they inter-relate and complement each other with their protective features. The effort, however, is worth the investment in learning how to use them.

Phishing and email spam are the biggest opportunities for hackers to enter the network. If a single user clicks on some malicious email attachment, it can compromise an entire enterprise with ransomware, cryptojacking scripts, data leakages, or privilege escalation exploits. Despite making some progress, a trio of email security protocols has seen a rocky road of deployment in the past year. Going by their acronyms SPF, DKIM and DMARC, the three are difficult to configure and require careful study to understand how they inter-relate and complement each other with their protective features. The effort, however, is worth the investment in learning how to use them.

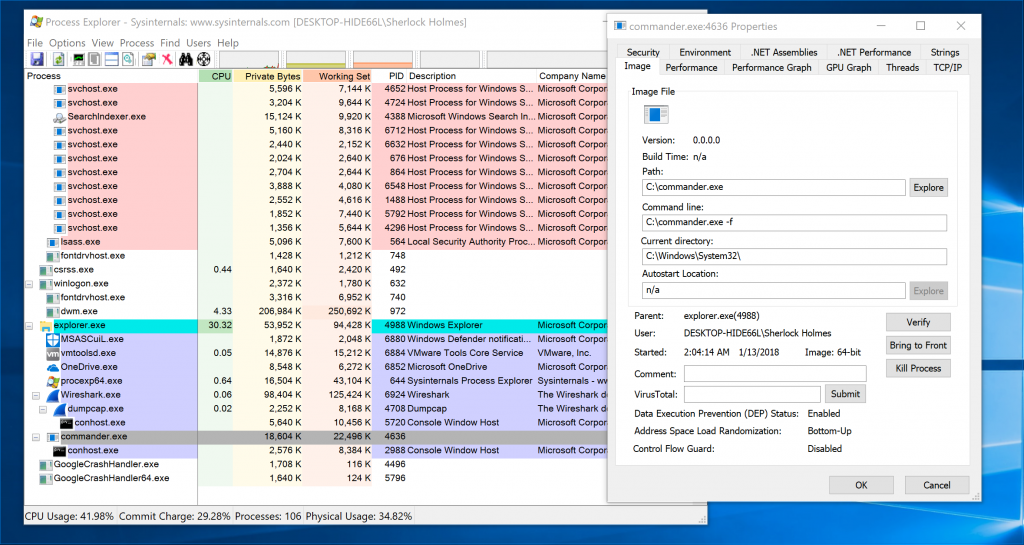

Organizations are becoming increasingly digital in their operations, products and services offerings, as well as with their business methods. This means they are introducing more technology into their environment. At the same time, they have shrunk their IT shops – in particular, their infosec teams – and have less visibility into their environment and operations. While they are trying to do more with fewer staff, they are also falling behind in terms of tracking potential security alerts and understanding how attackers enter their networks. Unfortunately, threats are more complex as criminals use a variety of paths such as web, email, mobile, cloud, and native Windows exploits to insert malware and steal a company’s data and funds.

Organizations are becoming increasingly digital in their operations, products and services offerings, as well as with their business methods. This means they are introducing more technology into their environment. At the same time, they have shrunk their IT shops – in particular, their infosec teams – and have less visibility into their environment and operations. While they are trying to do more with fewer staff, they are also falling behind in terms of tracking potential security alerts and understanding how attackers enter their networks. Unfortunately, threats are more complex as criminals use a variety of paths such as web, email, mobile, cloud, and native Windows exploits to insert malware and steal a company’s data and funds. These efforts have been known for some time: Motherboard ran a story in April 2016, and then came out in

These efforts have been known for some time: Motherboard ran a story in April 2016, and then came out in  Email is inherently insecure. Sorry, it has been that way since its invention, and still is. All of us don’t give its security the attention it needs and deserves. So if you got one of these messages, or if you are worried about your exposure to a future one, I have a few suggestions.

Email is inherently insecure. Sorry, it has been that way since its invention, and still is. All of us don’t give its security the attention it needs and deserves. So if you got one of these messages, or if you are worried about your exposure to a future one, I have a few suggestions.

Here is the thing. In order to install one of these keyboard apps, you have to grant it access to your phone. This seems like common sense, but sadly, this also grants the app access to pretty much everything you type, every piece of data on your phone, and every contact of yours too. Apple calls this full access, and they require these keyboards to ask explicitly for this permission after they are installed and before you use them for the first time. Many of us don’t read the fine print and just click yes and go about our merry way.

Here is the thing. In order to install one of these keyboard apps, you have to grant it access to your phone. This seems like common sense, but sadly, this also grants the app access to pretty much everything you type, every piece of data on your phone, and every contact of yours too. Apple calls this full access, and they require these keyboards to ask explicitly for this permission after they are installed and before you use them for the first time. Many of us don’t read the fine print and just click yes and go about our merry way. On Android phones, the permissions are a bit more granular, as you can see in this screenshot. This is actually just half of the overall permissions that are required.

On Android phones, the permissions are a bit more granular, as you can see in this screenshot. This is actually just half of the overall permissions that are required.