Two reports, one recent and one from last year have been published about the state of active cyber defense strategies.

The first one is Into the Gray Zone: The Private Sector and Active Defense Against Cyber Threats, it covers the work of a committee of government and industry experts put together by the Center for Cyber and Homeland Security of George Washington University and came out last October. The second report just came out this month and is called, Private Sector Cyber Defense: Can Active Measures Help Stabilize Cyberspace? It is published by Wyatt Hoffman and Eli Levite, two fellows at the Carnegie Endowment, a DC think tank.

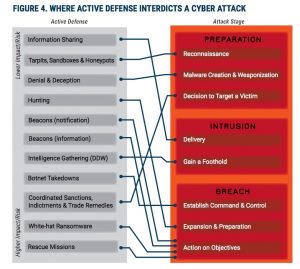

Both reports review the range of active cyber defense strategies. There are a variety of techniques that range from the more common honeypots (where IT folks set up a decoy server that looks like it contains important information but is used as a lure to attract hackers) to botnet takedowns to using white-hat (or legal uses of) ransomware to using cyber ‘dye-packs’ to collect network information from a hacker and possibly destroying his equipment, to other hacking back activities. The issue is where to draw the legal line for both the government and private actors.

Active defense is nothing new: honeypots were used back in 1986 by Clifford Stoll, who created fake files promising military secrets to lure a spy onto his network. He documented the effort in his book The Cuckoo’s Egg. Of course, since then people have gotten more sophisticated in their defense mechanisms, particularly as the number of attacks and their sophistication has grown.

The first report dissects two active defense case studies that are available in the public literature: Google’s reaction to Operation Aurora in 2009 that began in China and the Dridex banking Trojan botnet takedown in 2015. Google made use of questionably legal discovery technologies but was never prosecuted by any law enforcement agency. Dridex was neutralized through cooperation of several government agencies and private sector efforts, and resulted in the extradition and conviction of Andrey Ghinkul.

With both of these cases, the GWU report shows that attribution of the source of the malware was possible, but not without a lot of tremendous cooperation from a variety of private and government sources. That is the good news.

Speaking of cooperation, that is where the second report comes into play, where it compares the cyber efforts with the commercial shipping industry’s experience regarding piracy on the high seas. After it became clear that governments’ military efforts were insufficient responses to the piracy problem, the demand for private sector security services increased dramatically. While governments initially resisted their involvement, they begrudgingly accepted that the active defense measures deployed by shipowners, in consultation with insurance providers, were helping to deter attacks and that the tradeoffs in risk were unavoidable. The bottom line—the private sector filled a critical gap in protection by working together.

But here is the problem, as true now as last fall when the first GWU report was published. A private business has no explicit right of self-defense when it comes to a cyber attack, and in most cases, could be doing something that runs afoul of US laws. There are various legal remedies that the government can take, but not an ordinary business. As the GWU report states, “US law is commonly understood to prohibit active defense measures that occur outside the victim’s own network. This means that a business cannot legally retrieve its own data from the computer of the thief who took it, at least not without court-ordered authorization.” What makes matters worse is the number of cyber job openings in those government agencies, so even though they have the authority, they are woefully understaffed to take any action.

The GWU report puts forth a risk-based framework for how government and the private sector can work together to solve this problem, and you can read their various recommendations if you are interested.

It is a tricky situation. One of the GWU report authors is Nuala O’Connor, the President and CEO of the Center for Democracy & Technology. She says that “as more aggressive active defense measures might become lawful are based on considerations like whether they were conducted in conjunction with the government and the intent of the actor,” there could be problems. “I believe these types of measures should remain unlawful. Intent can be difficult to measure, particularly when on the receiving end of an effort to gain access.”

The Carnegie authors admit that their shipping analogy has its limitations, but correctly point out that when the government is lacking in its efforts, the private sector will step in and fill the gap with their own solutions. They say, “Malicious cyber actors motivated by geopolitical objectives, however, may have a far different calculus than cybercriminals, which affects whether and how they can be deterred.” In the meantime, my point in bringing up this issue is to get you to think about your own active cyber defense strategies for your own business.

There’s no shortage of people willing to bash bad PR practices, but we prefer to take a more positive tone. This week we speak with someone who does B2B PR very well.

There’s no shortage of people willing to bash bad PR practices, but we prefer to take a more positive tone. This week we speak with someone who does B2B PR very well.