We all know that the pandemic has had a major impact on employment patterns: not just more people working from home, but fewer people returning to their pre-Covid jobs. This has revealed what journalist Charlie Warzel calls career skeptics. His original piece can be found here, where he says folks don’t reject how they navigate their careers, but a complete rejection of having a career. That post received a sharply divided reaction from his readers: one group agreed with his point of view, but another felt the skeptics were a bunch of entitled complainers with a poor work ethic.

I have had essentially four careers. The first began when I was still in college and with a full-time job in my senior year as a professional photographer for the City of Albany, NY. It only lasted a year and only paid $5000 but it was the prototypical “foot in the door” in a very competitive profession. How competitive? After the job ended, I came to New York City with my portfolio in hand to try to get a job with a photographer. It was depressing: most of the people I tried to talk to wouldn’t even give me the time of day. Some just laughed at me: “What New York City (with emphasis on the last word) experience do you have?”

One of the photographers who actually let me in his door was W. Eugene Smith, the celebrated magazine photojournalist who was a few years away from his death. When I saw him he was in poor health, after being poisoned by covering the Minamata Mercury pollution story. He was very kind, although also very critical about my work. But just being able to spend a few moments with him made me realize that I had a long way to go, and that photography wasn’t in the cards in terms of my own career.

One of the photographers who actually let me in his door was W. Eugene Smith, the celebrated magazine photojournalist who was a few years away from his death. When I saw him he was in poor health, after being poisoned by covering the Minamata Mercury pollution story. He was very kind, although also very critical about my work. But just being able to spend a few moments with him made me realize that I had a long way to go, and that photography wasn’t in the cards in terms of my own career.

That “decisive moment” (to quote from another photographer) with Smith is what I guess many people are going through right now with their own career decisions. Maybe they don’t have a famous person giving them advice. Maybe they are seeing what their contemporaries are doing and want to find something else. My point is that you don’t necessarily have to stop at one career, if you understand your motivations and why you aren’t happy with your current job.

My other three careers were more successful: as a policy analyst in Washington DC and then various roles in IT and finally as you probably know me as a tech journalist. Early into that second career – in fact, at the end of my first job and about to take a second job offer – I remember a conversation with my dad, who ended up working for the same employer for decades as an accountant. I had just finished two years with the first firm, and he cautioned me that the change in jobs was too quick and wouldn’t look good for any future employer. It seems so quaint now, where a two-year tenure is almost too long in some quarters. My point here is that times change, and how our careers evolve need to be considered in the context of the times.

Warzel posits that our culture should perhaps aspire to better relations between employers and employees: the old saw that a company owes you nothing more than a paycheck and a safe working environment aren’t enough in today’s world where career development, intellectual stimulation, and doing something good for the world should motivate people to come to work, or at least come to their laptops in their spare bedrooms.

But that brings up another issue that is bugging me, and that is how we monitor our newly remote work forces. Employers are using increasingly intrusive monitoring software to track what their remote workers are doing, according to this piece in the Washington Post. This software category has exploded: It used to be just time and keystroke tracking, but now these tools can take screen captures, record video and ambient audio as well as track browser URLs and track geolocation. These tools include products such as Hubstaff, DeskTime, VeriClock and ActivTrack, and their use is growing quickly. PC Magazine even has a review of the category here. They say that “solutions that have been traditionally focused on tracking employee activity, logging suspicious behavior, and sniffing out possible insider threats are now pivoting to not only track productivity, but also monitor health and wellness, and even improve engagement.”

That frankly scares me. If we want to develop better employee/employer engagement, we have to start out trusting each other. Using more heavy-handed monitoring is a step backwards and could be yet another reason why employees aren’t returning to their pre-pandemic jobs — even if they don’t have to suffer long commutes to get to the office.

Back in the late 1980s, when I was a manager at PC Week, I supervised about a dozen people. Almost all of them were working remotely from our main office in downtown Boston. It was easy enough to measure their productivity: if the writer wrote his or her assigned stories, that was good enough for me. One of them was Bob who started out with a bang and then eventually tapered off to writing very few stories, and I had to fire him (the first person that I ever fired, by the way). Now, maybe your own productivity can’t be so quickly quantified, but I tried to give Bob the benefit of the doubt but after a month of no output and numerous requests to change his behavior I didn’t have much choice. That firing was a decisive moment for Bob, who went on for a second career as a pastor and talk show radio host.

The term conjures up glue guns and glitter, which isn’t a bad metaphor for what is really behind the term. In a 2007 paper written by academics, the authors talk about how employees should redesign their jobs to improve work satisfaction and engagement. If HGTV or DIY had shows about job crafting, they would show the before and after shots of tedium transformed into an exciting, vibrant workplace. Or something like that. (But please, no shiplap. I can’t stand shiplap.)

The term conjures up glue guns and glitter, which isn’t a bad metaphor for what is really behind the term. In a 2007 paper written by academics, the authors talk about how employees should redesign their jobs to improve work satisfaction and engagement. If HGTV or DIY had shows about job crafting, they would show the before and after shots of tedium transformed into an exciting, vibrant workplace. Or something like that. (But please, no shiplap. I can’t stand shiplap.) You might be trying to figure out which American news source I am talking about, but it is the website Rappler, The site was founded nearly ten years ago by Maria Ressa, who just shared the Nobel Peace Prize (and has numerous other awards including a Fulbright). Ressa’s Rappler has exposed a variety of Philippine government corruption scandals and various financial dirt and called attention to the anti-drug campaign that has resulted in the murder of thousands of supposed drug dealers.

You might be trying to figure out which American news source I am talking about, but it is the website Rappler, The site was founded nearly ten years ago by Maria Ressa, who just shared the Nobel Peace Prize (and has numerous other awards including a Fulbright). Ressa’s Rappler has exposed a variety of Philippine government corruption scandals and various financial dirt and called attention to the anti-drug campaign that has resulted in the murder of thousands of supposed drug dealers.

This episode brought us together with

This episode brought us together with  One of the photographers who actually let me in his door was W. Eugene Smith, the celebrated magazine photojournalist who was a few years away from his death. When I saw him he was in poor health, after being poisoned by covering the Minamata Mercury pollution story. He was very kind, although also very critical about my work. But just being able to spend a few moments with him made me realize that I had a long way to go, and that photography wasn’t in the cards in terms of my own career.

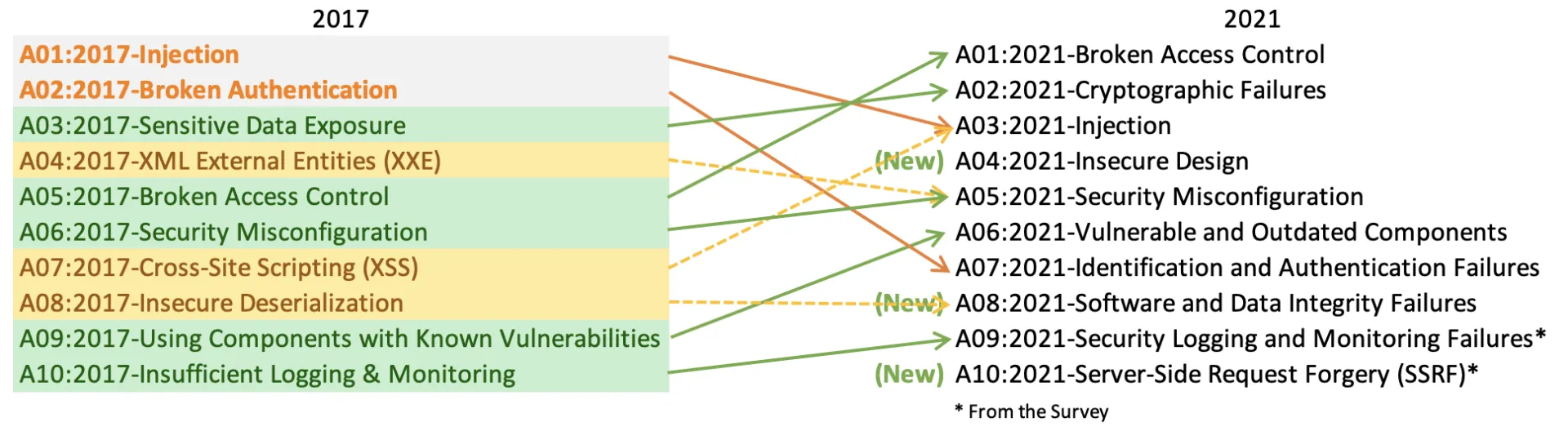

One of the photographers who actually let me in his door was W. Eugene Smith, the celebrated magazine photojournalist who was a few years away from his death. When I saw him he was in poor health, after being poisoned by covering the Minamata Mercury pollution story. He was very kind, although also very critical about my work. But just being able to spend a few moments with him made me realize that I had a long way to go, and that photography wasn’t in the cards in terms of my own career. Last week was the 20th anniversary of the Open Web Application Security Project (

Last week was the 20th anniversary of the Open Web Application Security Project (