For the past 27 years, I have owned a class C block of IPv4 addresses. I don’t recall what prompted me back then to apply to Jon Postel for my block: I didn’t really have any way to run a network online, and back then the Internet was just catching on. Postel had the unique position to personally attend to the care and growth of the Internet.

Earlier this year I got a call from the editor of the Internet Protocol Journal asking me to write about the used address marketplace, and I remembered that I still owned this block. Not only would he pay me to write the article, but I could make some quick cash by selling my block.

It was a good block, perhaps a perfect block: in all the time that I owned it, I had never set up any computers using any of the 256 IP addresses associated with it. In used car terms, it was in mint condition. Virgin cyberspace territory. So began my journey into the used marketplace that began just before the start of the new year.

It was a good block, perhaps a perfect block: in all the time that I owned it, I had never set up any computers using any of the 256 IP addresses associated with it. In used car terms, it was in mint condition. Virgin cyberspace territory. So began my journey into the used marketplace that began just before the start of the new year.

If you want to know more about the historical context about how addresses were assigned back in those early days and how they are done today, you’ll have to wait for my article to come out. If you don’t understand the difference between IPv4 and IPv6, you probably just want to skip this column. But for those of you that want to know more, let me give you a couple of pointers, just in case you want to do this yourself or for your company. Beware that it isn’t easy or quick money by any means. It will take a lot of work and a lot of your time.

First you will want to acquaint yourself with getting your ownership documents in order. In my case, I was fortunate that I had old corporate tax returns that documented that I owned the business that was on the ownership records since the 1990s. It also helped that I was the same person that was communicating with the regional Internet registry ARIN that was responsible for the block now. Then I had to transfer the ownership to my current corporation (yes, you have to be a business and fortunately for me I have had my own sub-S corps to handle this) before I could then sell the block to any potential buyer or renter. This was a very cumbersome process, and I get why: ARIN wants to ensure that I am not some address scammer, and that they are selling legitimate goods. But during the entire process my existing point of contact on my block, someone who wasn’t ever part of my business yet listed on my record from the 1990s, was never contacted about his legitimacy. I found that curious.

That brings up my next point which is whether to rent or to sell a block outright. It isn’t like deciding on a buying or leasing a car. In that marketplace, there are some generally accepted guidelines as to which way to go. But in the used IP address marketplace, you are pretty much on your own. If you are a buyer, how long do you need the new block – days, months, or forever? Can you migrate your legacy equipment to use IPv6 addresses eventually (in which cases you probably won’t need the used v4 addresses very long) or do you have legacy equipment that has to remain running on IPv4 for the foreseeable future?

If you want to dispose of a block that you own, do you want to make some cash for this year’s balance sheet, or are you looking for a steady income stream for the future? What makes this complicated is trying to have a discussion with your CFO how this will work, and I doubt that many CFOs understand the various subtleties about IP address assignments. So be prepared for a lot of education here.

Part of the choice of whether to rent or buy should be based on the size of the block involved. Some brokers specialize in larger blocks, some won’t sell or lease anything less than a /24 for example. “If you are selling a large block (say a /16 or larger) you would need to use a broker who can be an effective intermediary with the larger buyers,” said Geoff Huston, who has written extensively on the used IP address marketplace.

Why use a broker? When you think about this, it makes sense. I mean, I have bought and sold many houses — all of which were done with real estate brokers. You want someone that both buyer and seller can trust, that can referee and resolve issues, and (eventually) close the deal. Having this mediator can also help in the escrow of funds while the transfer is completed — like a title company. Also the broker can work with the regional registry staff and help prepare all the supporting ownership documentation. They do charge a commission, which can vary from several hundred to several thousand dollars, depending on the size of the block and other circumstances. One big difference between IP address and real estate brokers is that you don’t know what the fees are before you select the broker – which prevents you from shopping based on price.

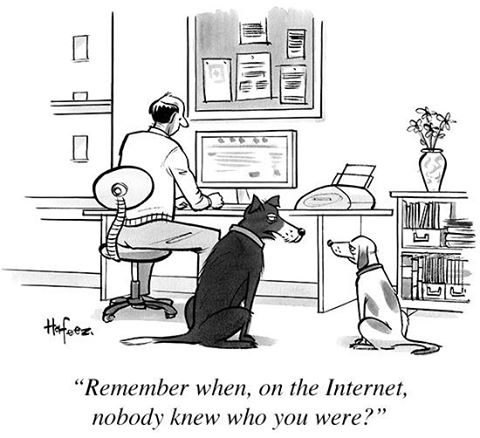

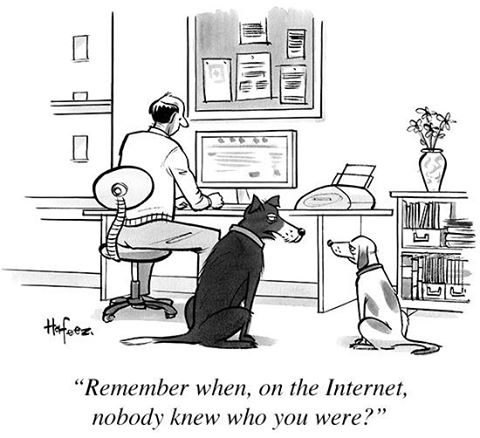

So now I had to find an address broker. ARIN has this list of brokers who have registered with them. They show 29 different brokers, along with contact names and phone numbers and the date that the broker registered with ARIN. Note this is not their recommendation for the reputation of any of these businesses. There is no vetting of whether they are still in business, or whether they are conducting themselves in any honorable fashion. As the old saying goes, on the Internet, no one knows if you could become a dog.

Vetting a broker could easily be the subject of another column (and indeed, I take some effort in my upcoming article for IPJ to go into these details). The problem is that there are no rules, no overall supervision and no general agreement on what constitutes block quality or condition. IPv4MarketGroup has a list of questions to ask a potential broker, including if they will only represent one side of the transaction (most handle both buyer and seller) and if they have appropriate legal and insurance coverage. I found that a useful starting point.

Vetting a broker could easily be the subject of another column (and indeed, I take some effort in my upcoming article for IPJ to go into these details). The problem is that there are no rules, no overall supervision and no general agreement on what constitutes block quality or condition. IPv4MarketGroup has a list of questions to ask a potential broker, including if they will only represent one side of the transaction (most handle both buyer and seller) and if they have appropriate legal and insurance coverage. I found that a useful starting point.

I picked Hilco’s IPv4.Global brokerage to sell my block. They came recommended and I liked that they listed all their auctions right from their home page, so you could spot pricing trends easily. For example, last month other /24 blocks were selling for $20-24 per IP address. Rental prices varied from 20 cents to US$1.20 per month per address, which means at best a two-year payback when rentals are compared to sales and at worst a ten-year payback. I decided to sell my block at $23 per address: I wanted the cash and didn’t like the idea of being a landlord of my block any more than I liked being a physical landlord of an apartment that I once owned. It took several weeks to sell my block and about ten weeks overall from when I first began the process to when I finally got the funds wired to my bank account from the sale.

If all that seems like a lot of work to you, then perhaps you just want to steer clear of the used marketplace for now. But if you like the challenge of doing the research, you could be a hero at your company for taking this task on.

We talk today with Dee Anna McPherson, the CMO at Invoca, an AI call tracking and conversational analytics vendor. That is a mouthful and one of the things she is doing is trying to define and own a new product category. That could be a daunting prospect, except she has done this before when she worked at Yammer (before they were engulfed by Microsoft) and then at Hootsuite. When Yammer began, no one had heard about microblogging, as it was called then. McPherson managed to define “enterprise social networking” as Yammer’s category and the company was off to the races from there. With working from home now the norm, that kind of technology has become the de factor standard for communications among remote team members.

We talk today with Dee Anna McPherson, the CMO at Invoca, an AI call tracking and conversational analytics vendor. That is a mouthful and one of the things she is doing is trying to define and own a new product category. That could be a daunting prospect, except she has done this before when she worked at Yammer (before they were engulfed by Microsoft) and then at Hootsuite. When Yammer began, no one had heard about microblogging, as it was called then. McPherson managed to define “enterprise social networking” as Yammer’s category and the company was off to the races from there. With working from home now the norm, that kind of technology has become the de factor standard for communications among remote team members.

Finally, case studies can have a visual element, as this

Finally, case studies can have a visual element, as this