Balancing anonymity and privacy isn’t an either/or situation. There are many shades of gray, and it is more of an art than science. Making sure your users understand the distinction between the two terms and setting their appropriate expectations of both should be a critical part of any job managing IT security.

Balancing anonymity and privacy isn’t an either/or situation. There are many shades of gray, and it is more of an art than science. Making sure your users understand the distinction between the two terms and setting their appropriate expectations of both should be a critical part of any job managing IT security.

Most users when they say they want anonymity really are saying that they don’t want anyone –whether it be the government or an IT department — to keep track their web searches and conversations. They will say they want some amount of privacy when they are at work, whether they are using their computers and phones for work-related tasks or not.

Certainly, part of the problem is that people today over-share online: they post photos of themselves at various restaurants, or are tagged by their social media “friends” in awkward situations, or post their travel itineraries down to the exact hotels they stay at. How hard would it be to intercept their communications, break into an unoccupied home, or steal a laptop from their hotel room with this information?

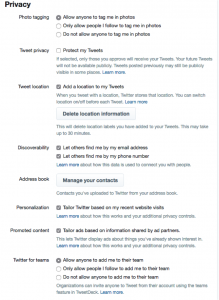

But part of the problem is that controlling our privacy is complex: Take a look at the typical controls offered by Twitter. How can any normal person figure these out, let alone remember to change any of them as their needs change? It is hopeless.

As I wrote about this for another blog post, many enterprises are deleting their most sensitive data so they don’t have to worry about potential and embarrasing leaks. Some are also making sure they own their own encryption keys, rather than trust them in the hands of some well-meaning third party. And Apple has recently announced changes to its iOS 11 that will make it harder for law enforcement to extract your personal data.

Sometimes, the purported solutions to privacy controls only make things worse. Windows 10 comes with a series of “personalization” settings that are enabled for the maximum intrusion into our lives by default. One of them – letting ads access a specially-coded ID that is stored on your computer to personalize messages for you – is presented in a way to “improve your experience.” If you choose this route, this translates to increasing the creepiness factor, as ads are served up online based on your browsing history.

As another example, technology often gives us a false sense of security. Just because your users enable private browsing or connect to the Internet through a proxy server doesn’t mean people can’t figure out who you actually are or target ads to your browsing history. Recently, researchers have found flaws in the extension APIs of all browsers that make it easier to fingerprint anyone. Called the WebExtensions API, this protects browsers against attackers trying to list installed extensions by using access control settings in the form of the manifest.json file included in every extension. This file blocks websites from checking any of the extension’s internal files and resources unless the manifest.json file is specifically configured to allow it. But it could be leveraged through this flaw.

Even when this is patched, big data has made it almost absurdly easy to figure out supposedly anonymous users. Remember this New York Times article? Reporters chose a single random user from this list of 20 million Web search queries collected by AOL back in 2006. The Times was able to track her down, a 62-year-old widow who immediately recognized her web searches. So much for being anonymous! And that was back in 2006: imagine other data repositories and tools that are available now to track down individuals with relative ease.

So, realize that privacy isn’t the same as anonymity. Just because I do not know you are does not mean that you have any privacy. Someone who captures my face when I am out on a remote hiking trail can still expose my location and my name through the auspices of Facebook’s facial recognition algorithms, and I could be tagged without my knowledge.

IT needs to understand the differences between privacy and anonymity, and be able to clearly communicate this information to its users. Part of this is having a clearly stated privacy policy on the corporate webpage – and then following it. (This one from email vendor Mailpile is exemplary.) They need to set policies for how the enterprise will track cookies, browsing sessions, metadata and the actual private details of their employees, if these items are tracked.

The odd thing about this person is that he is still a kid, an 11-year-old to be exact. His name is Reuben Paul and he lives in Austin. Reuben already has spoken at numerous infosec conferences around the world, and he “owned the room,” as one of the generals who runs one of the security services mentioned in a subsequent speech. What made Reuben (I can’t quite bring myself to use his last name as common style dictates, sorry) so potent a speaker is that he was funny and self-depreciating as well as informative. He was both entertaining as well as instructive. He did his signature story, as we in the speaking biz like to call it, a routine where he hacks into a plush toy teddy bear (shown here sitting next to him on the couch along with Janice Glover-Jones, who is the CIO for the Defense Intelligence Agency) using a Raspberry Pi connected to his Mac.

The odd thing about this person is that he is still a kid, an 11-year-old to be exact. His name is Reuben Paul and he lives in Austin. Reuben already has spoken at numerous infosec conferences around the world, and he “owned the room,” as one of the generals who runs one of the security services mentioned in a subsequent speech. What made Reuben (I can’t quite bring myself to use his last name as common style dictates, sorry) so potent a speaker is that he was funny and self-depreciating as well as informative. He was both entertaining as well as instructive. He did his signature story, as we in the speaking biz like to call it, a routine where he hacks into a plush toy teddy bear (shown here sitting next to him on the couch along with Janice Glover-Jones, who is the CIO for the Defense Intelligence Agency) using a Raspberry Pi connected to his Mac. In the intervening years since that story, tracking technology has gotten better and Internet privacy has all but effectively disappeared. At the DEFCON trade show a few weeks ago in Vegas, researchers presented a paper on how easy it can be to track down folks based on their digital breadcrumbs. The researchers set up a phony marketing consulting firm and requested anonymous clickstream data to analyze. They were able to actually tie real users to the data through a series of well-known tricks, described in this

In the intervening years since that story, tracking technology has gotten better and Internet privacy has all but effectively disappeared. At the DEFCON trade show a few weeks ago in Vegas, researchers presented a paper on how easy it can be to track down folks based on their digital breadcrumbs. The researchers set up a phony marketing consulting firm and requested anonymous clickstream data to analyze. They were able to actually tie real users to the data through a series of well-known tricks, described in this