When I first heard about the heroic efforts during WWII to break the Nazi communications codes such as Enigma, I had in my mind the image of a lone cryptanalyst with pencil and paper trying to figure out solutions, or using a series of mechanical devices such as the Bombe to run through the various combinations.

When I first heard about the heroic efforts during WWII to break the Nazi communications codes such as Enigma, I had in my mind the image of a lone cryptanalyst with pencil and paper trying to figure out solutions, or using a series of mechanical devices such as the Bombe to run through the various combinations.

But it turns out I couldn’t be more wrong. The efforts of the thousands of men and women stationed at Bletchley Park in England were intensely collaborative, and involved a flawless execution of a complex series of steps that were very precise. And while the Enigma machines get a lot of the publicity, the real challenge was a far more complex German High Command code called Lorenz, after the manufacturer of the coding machines that were used.

The wartime period has gotten a lot of recent attention, what with a new movie about Alan Turing just playing in theaters. This got me looking around the Web to see other materials, and my weekend was lost in watching a series of videos filmed at the National Museum of Computing at Bletchley Park. The videos show how the decoding process worked using the first actual electronic digital computer called Colossus. Through the efforts of several folks who maintained the equipment during wartime, the museum was able to reconstruct the device and have it in working order. This is no small feat when you realize that most of the wiring diagrams were immediately destroyed after the war ended, for fear that they would fall into the wrong hands. And that many people are no longer alive who attended to Colossus’ operations.

The name was realistic in several ways: first, the equipment easily filled a couple of rooms, and used miles of wires and thousands of vacuum tubes. At the time, that was all they had, since transistors weren’t to be invented for several years. Tube technology was touchy and subject to failure. The Brits figured out that if they kept Colossus running continuously, they would last longer. It also wielded enormous processing power, with a CPU that could have had a 5 MHz rating. This surpassed the power of the original IBM PC, which is pretty astounding given the many decades in between the two.

But the real story about Colossus isn’t the hardware, but the many people that worked around it in a complex dance to input and transfer data from one part of it to another. Back in the 1940s we had punch paper tape. My first computer in high school had this too and let me tell you using paper tape was painful. Other data transfers happened manually copying information from a printed teletype output into a series of plug board switches, similar to the telephone operator consoles that you might recall from a Lily Tomlin routine. And given the opportunity to transfer something in error, the settings would have to be rechecked carefully, adding more time to the decoding process.

There is an interesting side note, speaking about mistakes. The amount of sheer focus that the Bletchley teams had on cracking German codes was enormous. Remember, the codes were transmitted over the air in Morse. It turns out the Germans made a few critical mistakes in sending their transmissions, and these mistakes were what enabled the codebreakers to figure things out and actually reconstruct their own machines. Again, when you think about the millions of characters transmitted and just finding these errors, it was all pretty amazing.

What is even more remarkable about Colossus was that people worked together without actually knowing what they did. There was an amazing amount of wartime secrecy and indeed the existence of Colossus itself wasn’t well known until about 15 or 20 years ago when the Brits finally lifted bans on talking about the machine. For example, several of the Colossus decrypts played critical roles in the success of the D-Day Normandy invasion.

At its peak, Bletchley employed 9,000 people from all walks of life, and the genius was in organizing all these folks so that its ultimate objective, breaking codes, really happened. One of the principle managers, Tommy Flowers, is noteworthy here and actually paid for the early development out of his own pocket Another interesting historical side note is the contributions of several Polish mathematicians too.

As you can see, this is a story about human/machine collaboration that I think hasn’t been equaled since. If you are looking for an inspirational story, take a closer look at what happened here.

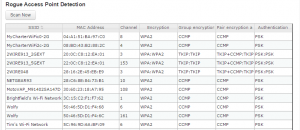

Overall, the market has slowly evolved more than had any big revolutionary changes. Products are getting better in terms of features and price/performance. All six of these units will do fine for securing small offices of 25 people.

Overall, the market has slowly evolved more than had any big revolutionary changes. Products are getting better in terms of features and price/performance. All six of these units will do fine for securing small offices of 25 people. Here is my modest plan. As many of you also know, for the past 12 or so years I have reached out to you and asked for you to support one of my charitable fundraising efforts that are usually accompanied by an organized bicycle ride. Over the years I have managed to raise tens of thousands of dollars for various causes like Juvenile Diabetes, cancer and MS. Today it is time to raise money for Ferguson. Several of the local businesses now have GoFundMe crowdsourced pages and are raising funds, because they want to stay in business. A few national reporters are mentioning these pages, which is great. I have tried to find ones that are still far behind on their goals but worthwhile efforts nonetheless. I would like you to take a moment, pick one (or more, if you are feeling generous), and send in your money. I have supported all of them to show that my concern is genuine.

Here is my modest plan. As many of you also know, for the past 12 or so years I have reached out to you and asked for you to support one of my charitable fundraising efforts that are usually accompanied by an organized bicycle ride. Over the years I have managed to raise tens of thousands of dollars for various causes like Juvenile Diabetes, cancer and MS. Today it is time to raise money for Ferguson. Several of the local businesses now have GoFundMe crowdsourced pages and are raising funds, because they want to stay in business. A few national reporters are mentioning these pages, which is great. I have tried to find ones that are still far behind on their goals but worthwhile efforts nonetheless. I would like you to take a moment, pick one (or more, if you are feeling generous), and send in your money. I have supported all of them to show that my concern is genuine.