The short answer is a resounding Yes! Let’s discuss this topic which has spanned generations.

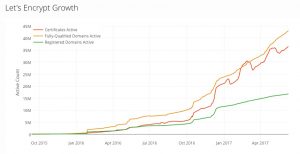

The current case in point has to do with terrorists using WhatsApp. For those of you that don’t use it, it is a text messaging app that also enables voice and video conversations. I started using it when I first went to Israel, because my daughter and most of the folks that I met there professionally were using it constantly. It has become a verb, like Uber and Google are for getting a ride and searching for stuff. Everything is encrypted end-to-end.

This is why the bad guys also use it. In a story that my colleague Lisa Vaas posted here in Naked Security, she quotes the UK Home Secretary Amber Rudd about some remarks she recently made. For those of you that aren’t familiar with UK government, this office covers a wide collection of duties, mixing what Americans would find in our Homeland Security and Justice Departments. She said, “Real people often prefer ease of use and a multitude of features to perfect, unbreakable security.” She was trying to make a plea for tech companies to loosen up their encryption, just a little bit mind you, because of the inability for her government to see what the terrorists are doing. “However, there is a problem in terms of the growth of end-to-end encryption” because police and security services aren’t “able to access that information.” Her idea is to serve warrants on the tech companies and get at least metadata about the encrypted conversations.

This sounds familiar: after the Paris Charlie Hebdo attacks two years ago. The last person in her job, David Cameron, issued similar calls to break into encrypted conversations. They went nowhere.

Here is the problem. You can’t have just a little bit of encryption, just like you can’t be a little bit pregnant. Either a message (or an email or whatever) is encrypted, or it isn’t. If you want to selectively break encryption, you can’t guarantee that the bad guys can’t go down this route too. And if vendors have access to passwords (as some have suggested), that is a breach “waiting to happen,” as Vaas says in her post. “Weakening security won’t bring that about, however, and has the potential to make matters worse.”

In Vaas’ post, she mentions security expert Troy Hunt’s tweet (reproduced here) showing links to all the online services that (surprise!) she uses that operate with encryption like Wikipedia, Twitter and her own website. Jonathan Haynes, writing in the Guardian, says “A lot of things may have changed in two years but the government’s understanding of information security does not appear to be one of them.”

In Vaas’ post, she mentions security expert Troy Hunt’s tweet (reproduced here) showing links to all the online services that (surprise!) she uses that operate with encryption like Wikipedia, Twitter and her own website. Jonathan Haynes, writing in the Guardian, says “A lot of things may have changed in two years but the government’s understanding of information security does not appear to be one of them.”

It isn’t that normal citizens or real people or whatever you want to call non-terrorists have nothing to hide.They do have their privacy, and if we don’t have encryption, then everything is out in the open for anyone to abuse, lose, or spread around the digital landscape.

In the old days — perhaps one or two years ago — security professionals were fond of saying that you need multiple authentication factors (MFAs) to properly secure login identities. But that advice has to be tempered with the series of man-in-the-middle and other malware exploits on MFAs that nullify the supposed protection of those additional factors. Times are changing for MFA, to be sure.

In the old days — perhaps one or two years ago — security professionals were fond of saying that you need multiple authentication factors (MFAs) to properly secure login identities. But that advice has to be tempered with the series of man-in-the-middle and other malware exploits on MFAs that nullify the supposed protection of those additional factors. Times are changing for MFA, to be sure.