Remember Mirai? This four-year old botnet was the scourge of the internet and used as the launching pad for numerous DDoS attacks. It continues to be the basis for new attacks, and I blog about this for Avast here. There are several mitigation measures you can take, including using a free tool from F-Secure that can check your router for any potential weaknesses. You might also use this to put a more complete program in place to ensure all critical network infrastructure has appropriately complex and unique passwords.

Category Archives: security

Lessons learned from the Home Depot breach

You might have forgotten about the massive Home Depot data breach. After all, it happened in 2014. More then 56M customers’ payment card data was exposed as a result of malware being installed on the self-checkout lanes in numerous stores. (While I haven’t been in any store in a while, I do recall those self-checkout lanes to be annoying and spending time rescanning my items.) The malware operated for several months before it was detected and removed. At the time, it was the largest breach on record. The main cause of the breach was stolen third-party credentials. A report that SANS has put together is an excellent analysis of what happened.

You might have forgotten about the massive Home Depot data breach. After all, it happened in 2014. More then 56M customers’ payment card data was exposed as a result of malware being installed on the self-checkout lanes in numerous stores. (While I haven’t been in any store in a while, I do recall those self-checkout lanes to be annoying and spending time rescanning my items.) The malware operated for several months before it was detected and removed. At the time, it was the largest breach on record. The main cause of the breach was stolen third-party credentials. A report that SANS has put together is an excellent analysis of what happened.

The company was fined $17.5M as a result as part of a settlement which was announced this past week with various state and federal officials. Reviewing the press release was quite revealing (for once) because it lists a number of action items that Home Depot had agreed to implement to prevent further breaches. These include:

- Having a Chief Information Security Officer report to C-level executives and the Board of Directors

- Providing resources necessary to fully implement the company’s information security program, including a comprehensive security awareness and privacy training program

- Employing specific security safeguards with respect to logging and monitoring, access controls, password management, two-factor authentication, file integrity monitoring, firewalls, and data encryption controls

- Regular vulnerability scans of their networks that includes risk assessments, penetration testing, intrusion detection, and vendor account management

- Appropriate network segmentation of their POS equipment and other sensitive areas

One would hope that in the past six years they have actually done all of these. Yes, our legal system moves quite slowly. But it is a handy reference list for all of us to evaluate the IT security of our own businesses. And it isn’t as simple as turning on all the features of their endpoint protection tool (something that Home Depot didn’t do back in 2014 for some odd reason) but implementing more system-wide efforts that need continuous attention. For example, the POS was running Windows XP, which was outdated and quite vulnerable even in 2014.

IT security isn’t a destination, but an evolutionary process. Take your eyes off the ball and you’ll find yourself in a similar situation to Home Depot.

Network Solutions blog: What is Identity and Access Management and How Does It Protect High-Profile Users?

My latest blog for Network Solutions is about identity and access management. Our email accounts have become our identity, for better and worse. Hackers exploit this dependency by using more clever phishing lures. Until recently, enterprises have employed very complex and sophisticated mechanisms to manage and protect our corporate identities and control access to our files and other network resources. What has changed recently are two programs from Microsoft and Google that are designed to help combat phishing. They are aimed at helping higher-risk users who want enterprise-grade identity and access management security without the added extra cost and effort to maintain it. The two programs are called AccountGuard (Microsoft) and Advanced Security (Google). In my blog post, I explain what these two programs are all about.

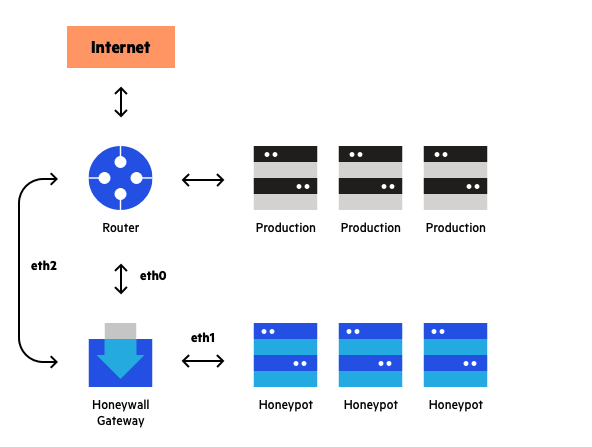

Network Solutions blog: Honeypot Network Security, What It Is and How to Use It Defensively

The original idea behind honeypot security was to place a server on some random Internet link and sit back and wait until some hacker happened by. The server’s sole purpose would be to record the break-in attempt — it would not be part of a normal applications infrastructure. Then a researcher would observe what happened to the server and what exploit was being used. A honeypot is essentially bait (passwords, vulnerabilities, fake sensitive data) that’s intentionally made very tempting and accessible. The goal is to deceive and attract a hacker who attempts to gain unauthorized access to your network.

The original idea behind honeypot security was to place a server on some random Internet link and sit back and wait until some hacker happened by. The server’s sole purpose would be to record the break-in attempt — it would not be part of a normal applications infrastructure. Then a researcher would observe what happened to the server and what exploit was being used. A honeypot is essentially bait (passwords, vulnerabilities, fake sensitive data) that’s intentionally made very tempting and accessible. The goal is to deceive and attract a hacker who attempts to gain unauthorized access to your network.

In this blog for Network Solutions, I describe their role in modern network security, compare the features of various commercial and open source products, and provide a series of tips on how to pick the right kind of deception product to fit your business’ needs.

Book and courseware review: Learning appsec from Tanya Janca

If you are looking to boost your career in application security, there is no better place to start than by reading a copy of Tanya Janca’s new book Alice and Bob Learn Application Security. The book forms the basis of her excellent online courseware on the same subject, which I will cover in a moment.

If you are looking to boost your career in application security, there is no better place to start than by reading a copy of Tanya Janca’s new book Alice and Bob Learn Application Security. The book forms the basis of her excellent online courseware on the same subject, which I will cover in a moment.

Janca has been doing security education and consulting for years and is the founder of We Hack Purple, an online learning academy, community and weekly podcast that revolves around teaching everyone to create secure software. She lives in Victoria BC, one of my favorite places on the planet, and is one of my go-to resources to explain stuff that I don’t understand. She is a natural-born educator, with a deep well of resources that comes not just from being a practitioner, but someone who just oozes tips and tools to help you secure your stuff.

Take these two examples from her book:

- First is a series of security tools. To try to keep her book focused, she doesn’t make these recommendations there but has plenty of online places such as this link where she makes suggestions.

- Second is this tweet stream about favorite topics by others (many of which did make it into her book)

The book is both a crash course for newbies as well as a refresher for those that have been doing the job for a few years. I learned quite a few things and I have been writing about appsec for more than a decade. The audience is primarily for application developers, but it can be a useful organizing tool for IT managers that are looking to improve their infosec posture, especially these days when just about every business has been penetrated with malware, had various data leaks, and could become a target from the latest Internet-based threat. Everyone needs to review their application portfolio carefully for any potential vulnerabilities since many of us are working from home on insecure networks and laptops.

Her rough organizing framework for the book has to do with the classic system development lifecycle that has been used for decades. Even as the nature of software coding has changed to more agile and containerized sprints, this concept is still worth using, if security is thought of as early in the cycle as possible. My one quibble with the book is that this framework is fine but there are many developers who don’t want to deal with this — at their own peril, sadly. For the vast majority of folks, though, this is a great place to start.

Alice and Bob are that dynamic duo of infosec that are often foils for good and bad practices, are used as teaching examples that reek of events drawn from Janca’s previous employers and consulting gigs.

For example, you’ll learn the differences between pepper and salt: not the condiments but their security implications. “No person or application should ever be able to speak directly to your database,” she writes. The only exceptions are your apps or your database admins. What about applications that make use of variables placed in a URL string? Not a good idea, she says, because a user could see someone else’s account, or leave your app open to a potential injection attack. “Never hard code anything, ever” is another suggestion because by doing so you can’t trust the application’s output, and the values that are present in your code could compromise sensitive data and secrets.

“When data is sensitive, you need to find out how long your app is required to store it and create a plan for disposing of it at the end of its life.” Another great suggestion for testing the security of your design is to look for places where there is implied trust, and then remove that trust and see what breaks in your app.

Never write your own security code if you can make use of ones that are part of your app dev framework. And spend time on improving your “soft skills” as a developer: meaning learning how to communicate with your less-technical colleagues. “This is especially true, when you feel that the sky is falling and you aren’t getting any management buy-in for your ideas.”

One topic that she returns to frequently is what she calls technical debt. This is a sadly too-often situation, whereby programmers make quick and dirty development decisions. It reflects the implied costs of reworking the code in your program due to taking shortcuts, shortcuts that eventually will catch up with you and have major security implications. She talks about how to be on the lookout and how to avoid this style of thinking.

Let’s move on to talk about the online classes.

The classes will cost $999 (with an option to interact directly with her for 30 minutes for an additional $300) but are certainly worth it. They cover three distinct areas, all of which are needed if your code is going to stand up against hackers and other adversaries.

The first course is for beginners, and covers the numerous areas of appsec that you will need to understand if you are going to be building secure apps from scratch, or trying to fix someone else’s mess. Even though I have been testing and writing about infosec for decades, I still managed to learn something from this class.

If you are not a beginner, and if you are just aiming to learn more for yourself, then you should probably just focus on the third class. The second class goes into more detail about how to create a culture at your organization where appsec is part of everyone’s job. If you aren’t going to be managing a development team, you might want to return to this class later on.

There are certainly many sources of online education, but surprisingly, few offer the range and depth that Janca has put together. Google and Microsoft have free classes to show you how to make use of their clouds, but they aren’t as comprehensive nor as useful, especially for beginners who may not even know how to frame the right questions, or even assemble their goals for what they want to learn about appsec. And both OWASP and SANS, which normally are my go-to places to learn something technical, are also deficient on the practice of appsec, although they both have developed many open-source tools and cheat sheets and other supporting things that are used in developing secure apps. Thus Janca’s courseware fills an important missing niche.

The textbook for all three classes is her excellent Alice and Bob book mentioned above. Yes, you could probably learn some of the things by just reading the book without taking the classes, but you would have to work a lot harder, especially if you are more of an auditory learner. Watching and listening to Janca explain her way through numerous different tools that you’ll need to build your apps securely is worth the price of the courses: you are in the presence of a master teacher who knows her stuff.

One thing missing from the trio of classes is any product-specific discussion. (She covers this separately.) I realize why she did this, but think that eventually you will be frustrated and just wish you could have a little more context of how a piece of defensive or detection software actually works, because that is how I, as an experiential learner, figure these things out.

All in all, I highly recommend the sequence, with the above caveats. We all need to move in the direction of making all of our apps more secure, and Janca’s courseware should be required for anyone and everyone.

RSA blog: Endpoints are our new security perimeters

Remember when firewalls first became popular? When enterprises began installing firewalls in earnest, they quickly defined our network’s protective perimeter. Over the years, this perimeter has evolved from a hardware focus to one more defined by software, to where Bruce Schneier officially proclaimed their ultimate death a few years ago.

Part of this evolution is the changing nature of the attacks we experience along with the changing nature of our enterprise networks. Back when everyone was working from well-defined offices, we could definitely state that there was a difference between what was considered “outside” and “inside” the corporate network. But then the Internet happened, and we all became connected. Even before the pandemic, there was little difference. With the advent of the cloud, and definitely since the pandemic began, we are all out. That wise infosec sage Jerry Seinfeld once said this in an opening monologue to his TV series in 1989. We no longer worry about “bringing your own device.” We are all working from home, using devices that aren’t necessarily ones that IT has purchased and sharing them with other family members. As my colleague Scott Fulton wrote about this in 2017, “Once the distinctions between inside and outside have been effectively erased, an outside user would be treated exactly the same as one inside the office.” You could argue that he was talking from the opposite perspective, but with the same result.

This has given rise to the concept of zero-trust networks, a topic that I touched upon in my March 2019 post. In that post, I talk about the shades of grey that are now accepted as part of the authentication process: not only is there no distinction between inside and outside the corporate network, but there is nothing that is fully trusted anymore. As I mentioned in that post, the zero-trust concept is really a misnomer: instead, we should strive for a zero-risk model. RSA CTO Dr. Zulfikar Ramzan has long advocated doing this, because it gets IT staffs to examine what is really important: identifying and securing key IT assets and data, as well as that from third parties.

Once consequence of a zero-risk model is that today the new network perimeter really depends on the integrity of our endpoint devices. The endpoint is the first thing that can fall victim to a phishing lure and it is the first place that attackers look for a sign of an unpatched OS or a smartphone that is secretly running malware. Recent surveys show that the pandemic is making it easier for cybercriminals to target mid-level managers, with various lures such as Covid-related ones to more traditional business impersonations.

That doesn’t mean we need to let a thousand firewalls bloom, but it does mean that endpoint detection and response tools have to do a lot more these days than just scan for malware and compromises. Instead, we need a whole army of protective features that is working for us, to prevent our endpoints from being an attractive place for attackers to try to leverage. The vendors in the endpoint space have risen to meet these challenges, and have added features such as:

- Ad hoc queries (to search for new compromises),

- Better security policy enforcement and reporting,

- Automatic discovery of outliers and unmanaged endpoints,

- Detection of lateral network movement (for better early attack notifications),

- Better remediation and deployment tactics (to upgrade large populations of outdated endpoints),

- Better patch management (ditto), and

- Integration into existing protective gear such as event and service management tools.

That is a tall order for any security tool to handle. But as we continue to work from home, we need the appropriate protection. As Pogo once said, “we have met the enemy and he is us.”

Avast blog: Understanding and preventing Cross-Site Scripting attacks

You wouldn’t think an attack method that was first found more than 20 years ago would be at the top of anyone’s list of popular current attacks. But that is the case for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), a method that was first discovered by Microsoft engineers at the turn of the century. Avast’s XSS explainer webpage goes into more detail about the different attack types and some of the more notable attacks and victims down through the years. Top marks were issued by MITRE’s Common Weakness Enumeration group, which also listed 24 other dangerous software weaknesses.

You wouldn’t think an attack method that was first found more than 20 years ago would be at the top of anyone’s list of popular current attacks. But that is the case for Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), a method that was first discovered by Microsoft engineers at the turn of the century. Avast’s XSS explainer webpage goes into more detail about the different attack types and some of the more notable attacks and victims down through the years. Top marks were issued by MITRE’s Common Weakness Enumeration group, which also listed 24 other dangerous software weaknesses.

I describe what all is involved with XSS attacks and some of the more notable ones of recent memory, along with how you can prevent them, in my blog post for Avast here.

Network Solutions blog: Ways to Identify and Prevent Vishing Attacks

In my latest blog post for Network Solutions, I explain vishing, or voice-based phishing attacks. It is a more modern and sophisticated version of a crank call. Only instead of being placed by bored teenagers, it is a very targeted and dangerous call that can get you to do the caller’s bidding. The vishers are getting more clever at constructing their lures and scams. Spoofing isn’t the only tool these guys abuse. Another is the underpinning of any good social engineering effort: collecting as much data about you as possible, to make their request more personal and more believable. My post has several suggestions to keep in mind the next time you get one of these calls.

In my latest blog post for Network Solutions, I explain vishing, or voice-based phishing attacks. It is a more modern and sophisticated version of a crank call. Only instead of being placed by bored teenagers, it is a very targeted and dangerous call that can get you to do the caller’s bidding. The vishers are getting more clever at constructing their lures and scams. Spoofing isn’t the only tool these guys abuse. Another is the underpinning of any good social engineering effort: collecting as much data about you as possible, to make their request more personal and more believable. My post has several suggestions to keep in mind the next time you get one of these calls.

Network Solutions blog: How to identify and prevent smishing attacks

By now we are all too familiar with phishing attacks. They have received lots of press coverage and are at the heart of many cyberattacks. But hackers are getting more specialized and have turned towards other variations, one of which goes by the term smishing. This is a combination of social engineering techniques that are sent over SMS texts rather than using the typical emails that traditional phishing lures use. SMS phishing, get it? In Verizon’s 2020 mobile security index, they found that 15% of enterprise users encountered a smishing link in Q3 2019. In my latest post for Network Solutions’ blog, I demonstrate how these kinds of attacks work, how the criminals have upped their game, and what you can do to protect yourself.

By now we are all too familiar with phishing attacks. They have received lots of press coverage and are at the heart of many cyberattacks. But hackers are getting more specialized and have turned towards other variations, one of which goes by the term smishing. This is a combination of social engineering techniques that are sent over SMS texts rather than using the typical emails that traditional phishing lures use. SMS phishing, get it? In Verizon’s 2020 mobile security index, they found that 15% of enterprise users encountered a smishing link in Q3 2019. In my latest post for Network Solutions’ blog, I demonstrate how these kinds of attacks work, how the criminals have upped their game, and what you can do to protect yourself.

Avast blog: One mo’ election update: ransomware

We’re less than a week away from the 2020 U.S. election, and there has been news of a ransomware attack in northern Georgia. The attack hit a network that supports the Hall County government infrastructure and includes election and telephone systems. It was the first time that systems were brought down, although it wasn’t the first time election systems have been targeted by ransomware. Those happened in Louisiana and Washington State, both unsuccessful. In my blog post today for Avast, I go into the details about these attacks and some of the deficient cybersecurity practices also happening in Georgia.