Have you ever heard of the following companies: Nordstar, S7, Angara, Amur or Barkol? Probably not. All of them are just some of the names of dozens of airlines operating in Russia. Right now, Russian airlines have a problem and they are about to make international insurance lawyers very busy for the next decade to solve it. The problem stems from the way that all modern airlines operate their fleets. Since the airspace restrictions and sanctions were imposed earlier this year, all Russian airlines can only fly domestically. Given that Russia has more than 500 daily domestic flights, you would think that would still be a viable market for them, but you would be wrong.

I am writing about the Russian plane problem because it is something that I can get my head around in this horrific war with Ukraine. My heart breaks as I try to follow the latest news and see the misery of millions fearing for their lives and fleeing to other parts of Europe that I never thought I would cast in a kind light. But I have to remember not to confuse the people of a country with its leaders, too.

I am writing about the Russian plane problem because it is something that I can get my head around in this horrific war with Ukraine. My heart breaks as I try to follow the latest news and see the misery of millions fearing for their lives and fleeing to other parts of Europe that I never thought I would cast in a kind light. But I have to remember not to confuse the people of a country with its leaders, too.

There are several problems with the planes.

First, there are more than 900 aircraft that are registered in Bermuda. Think of this as a “flag of convenience” as many ships are registered in Panama, but there is a separate complication. Bermuda has a very robust registration entity and favorable tax and treaty laws, so the Russian airlines have taken advantage of this and have registered more than 500 planes there. Last week, Bermuda pulled these registrations, fearing quite rightly that the planes will be held hostage as the war continues. The second problem is that the major aircraft manufacturers (Boeing and Airbus) have pulled their people and stopped parts shipments (so no one can maintain the planes). A third plane maker, Antonov, is based in Kyiv and its factory was recently bombed by the Russians. Planes require regular maintenance, but more importantly, they require people to log these repairs so insurers can be satisfied that the planes are safe and properly cared for.

The third issue is that many of the Russian planes are financed by leasing companies, which happen to be based in Ireland. Again, favorable taxes and treaties. The leasing companies tried to repo a few of the planes that were sitting outside of Russia when the sanctions went into effect, and managed to take control over a few (and lose a couple too). Now that is a high-stress job, being a plane repo dude.

The total value of the planes stuck in Russia was somewhere around $10B, including some brand new planes that were just delivered before the start of the war. The reason I say was is because their value will plummet even if they sit on the Russian tarmac: think of having your car sit in your garage for many months. Stuff just starts to deteriorate. So Russia is trying to do an end run around the Bermuda registration by passing a law that says they can re-register their planes in Russia, no harm no foul. Except registering a plane is a lot like registering a car: there is only one country allowed, and to change the registration involves some paperwork and agreements that aren’t just signing the plane over. For example, a lease becomes void when the registration changes. The international aviation industry has these rules, otherwise there would be chaos. Which there now is.

And the planes are just the beginning of other issues for Russia. This piece in CSOonline describes how Russia is disconnecting itself from the rest of the global internet by requiring use of its own digital certificates and DNS resolvers. We are witnessing the unbanking and disconnecting of Russia from the rest of the global economy. There is certainly more turbulence and misery ahead.

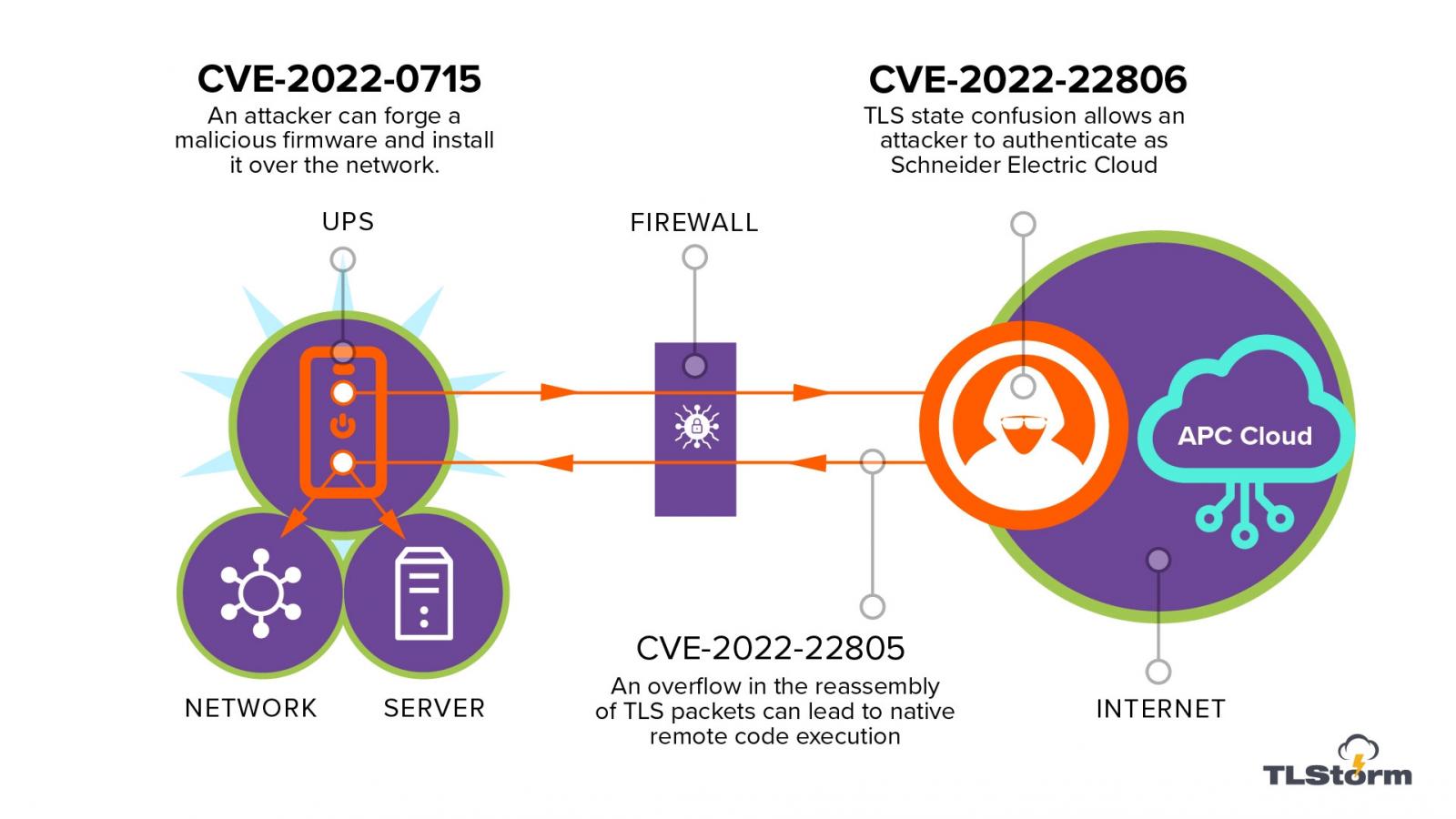

Security researchers have uncovered a new series of threats that are targeting uninterrupted power supply (UPS) units. These threats can result in malware attacking the computers connected to the same networks through a variety of clever mechanisms.

Security researchers have uncovered a new series of threats that are targeting uninterrupted power supply (UPS) units. These threats can result in malware attacking the computers connected to the same networks through a variety of clever mechanisms.

Misty Sutton never set out to work at the American Red Cross, but she quickly fell in love with both the mission and the overall organization. “I love that the Red Cross is neutral and provides universal assistance, no matter what the client’s circumstances might be,” she said.

Misty Sutton never set out to work at the American Red Cross, but she quickly fell in love with both the mission and the overall organization. “I love that the Red Cross is neutral and provides universal assistance, no matter what the client’s circumstances might be,” she said.