When evaluating managed security service providers (MSSPs), companies should make sure that web application security is part of the offering – and that a quality DAST solution is on hand to provide regular and scalable security testing. SMBs should evaluate potential providers based on whether they offer modern solutions and services for dynamic application security testing (DAST), as I wrote for the Invicti blog this month.

SiliconANGLE: As cloud computing gets more complex, so does protecting it. Here’s how to make sense of the market

Whether companies are repatriating their cloud workloads back on-premises or to colocated servers, they still need to protect them, and the market for that protection is suddenly undergoing some major changes. Until the past year or so, cloud-native application protection platforms, or CNAPPs for short, were all the rage. Last year, I reviewed several of them for CSOonline here. But securing cloud assets will require a multi-pronged approach and careful analysis of the organization’s cloud infrastructure and data collections. Yes, different tools and tactics will be required. But the lessons learned from on-premises security resources will point the way toward what to do in the cloud. More of my analysis can be found in this piece for SiliconANGLE.

SiliconANGLE: The chief trust officer was once the next hot job on executive row. Not anymore.

We seem to be in a trust deficit these days. Breaches – especially amongst security tech companies – continue apace. Ransomware attacks now have spread to data hostage events. The dark web is getting larger and darker, with enormous tranches of new private data readily for sale and criminal abuse. We have social media to thank for fueling the fires of outrage, and now we can self-select the worldview of our social graph based on our own opinions.

In this story for SiliconANGLE, I discuss the decline of digital trust and tie it to a new ISACA survey and a new effort by the Linux Foundation to try to document and improve things.

The art of mathematical modeling

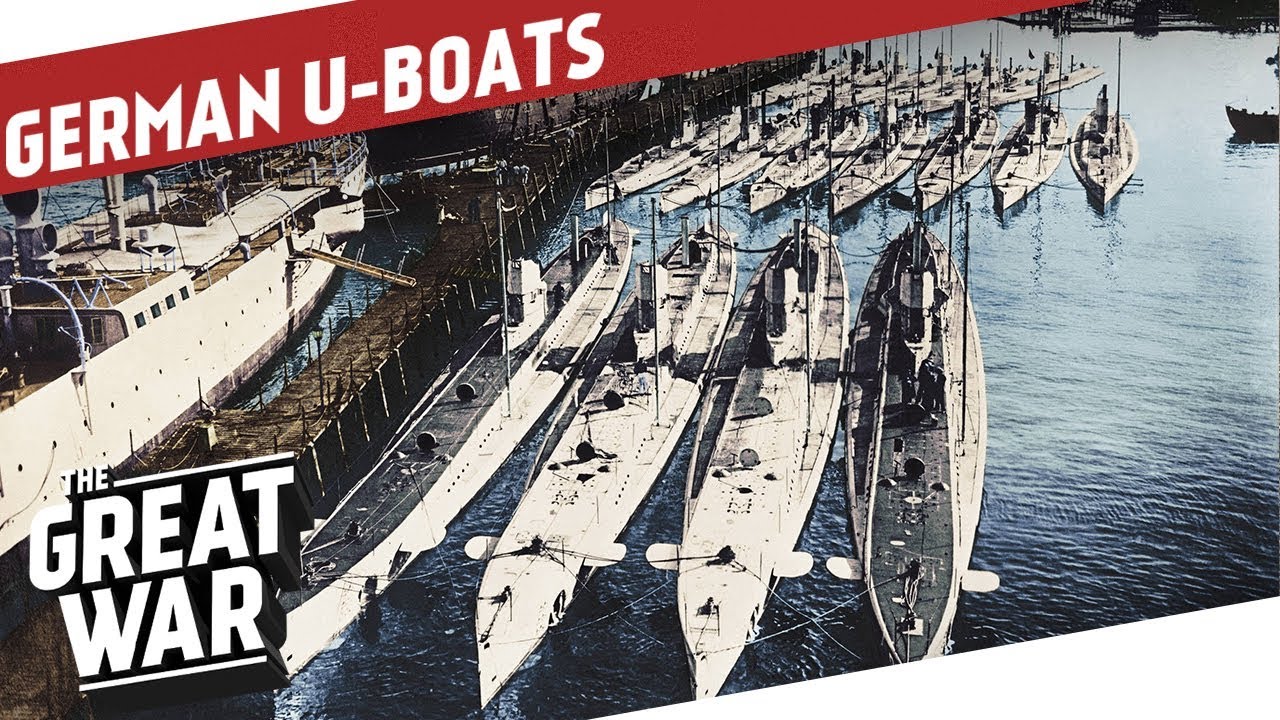

All this chatter about ChatGPT and large language models interests me, but from a slightly different perspective. You see, back in those pre-PC days when I was in grad school at Stanford, I was building mathematical models as part of getting my degree in Operations Research. You might not be familiar with this degree, but basically was applying various mathematical techniques to solving real-world problems. OR got its beginnings trying to find German submarines and aircraft in WWII, and then got popular for all sorts of industrial and commercial applications post-war. As a newly minted math undergrad, the field had a lot of appeal, and at its heart was building the right model.

All this chatter about ChatGPT and large language models interests me, but from a slightly different perspective. You see, back in those pre-PC days when I was in grad school at Stanford, I was building mathematical models as part of getting my degree in Operations Research. You might not be familiar with this degree, but basically was applying various mathematical techniques to solving real-world problems. OR got its beginnings trying to find German submarines and aircraft in WWII, and then got popular for all sorts of industrial and commercial applications post-war. As a newly minted math undergrad, the field had a lot of appeal, and at its heart was building the right model.

Model building may bring up all sorts of memories of putting together plastic replicas of cars and ships and planes that one would buy in hobby stores. But the math models were a lot less tangible and required some careful thinking about the equations you chose and what assumptions you made, especially on the initial data set that you would to train the model.

Does this sound familiar? Yes, but then and now couldn’t be more different.

For my class, I recall the problems that we had to solve each week weren’t easy. One week we had to build a model to figure out which school in Palo Alto we would recommend closing, given declining enrollment across the district, a very touchy subject then and now. Another week we were looking at revising the standards for breast cancer screening: at what age and under what circumstances do you make these recommendations? These problems could take tens of hours to come up with a working (or not) model.

I spoke with Adam Borison, a former Stanford Engineering colleague who was involved in my math modeling class: “The problems we were addressing in the 1970s were dealing with novel situations, and figuring out what to do, rather than what we had to know built around judgment, not around data. Tasks like forecasting natural gas prices. There was a lot of talk about how to structure and draw conclusions from Bayesian belief nets which pre-dated the computing era. These techniques have been around for decades, but the big difference with today’s models is the huge increment in computing power and storage capacity that we have available. That is why today’s models are more data heavy, taking advantage of heuristics.”

Things started to change in the 1990s when Microsoft Excel introduced its “Solver” feature, which allowed you to run linear programming models. This was a big step, because prior to this we had to write the code ourselves, which was a painful and specialized process, and the basic foundation of my grad school classes. (On the Stanford OR faculty when I was there were George Danzig and Gerald Lieberman, the two guys that invented the basic techniques.) My first LP models were written on punched cards, which made them difficult to debug and change. A single typo in our code would prevent our programs from running. Once Excel became the basic building block of modeling, we had other tools such as Tableau that were designed from the ground up for data analysis and visualizations. This was another big step, because sometimes the visualizations showed flaws in your model, or suggested different approaches.

Another step forward with modeling was the era of big data, and one example with the Kaggle data science contests. These have been around for more than a decade and did a lot to stimulate interest in the modeling field. Participants are challenged to build models for a variety of commercial and social causes, such as working on Parkinson’s cures. Call it the gamification of modeling, something that was unthinkable back in the 1970s.

But now we have the rise of the chatbots, which have put math models front and center, for good and for bad. Borison and I are both somewhat hesitant about these kinds of models, because they aren’t necessarily about the analysis of data. Back in my Stanford days, we could fit all of our training data on a single sheet of paper, and that was probably being generous. With cloud storage, you can have a gazillion bytes of data that a model can consume in a matter of milliseconds, but trying to get a feel for that amount of data is tough to do. “Even using ChatGPT, you still have to develop engineering principles for your model,” says Borison.”And that is a very hard problem. The chatbots seem particularly well-suited to the modern fast fail ethos, where a modeler tries to quickly simulate something, and then revise it many times.” But that doesn’t mean that you have to be good at analysis, just making educated guesses or crafting the right prompts. Having a class in the “art of chatbot prompt crafting” doesn’t quite have the same ring to it.

Who knows where we will end up with these latest models? It is certainly a far cry from finding the German subs in the North Atlantic, or optimizing the shortest path for a delivery route, or the other things that OR folks did back in the day.

SiliconANGLE: Boards of directors need to be more cyber-aware. That gets complicated.

The Securities and Exchange Commission proposed some new guidelines last year to promote better cybersecurity governance among public companies, and one of them tries to track the cybersecurity expertise of the boards of directors of these companies. Judging from a new study conducted by MIT Sloan cybersecurity researchers and recently published in the Harvard Business Review, it might work — though it also might backfire. In this analysis for SiliconANGLE, I discuss the pros and cons of these regs.

SiliconANGLE: Magecart malware strikes again, and again, at e-commerce websites

The shopping cart malware known as Magecart is still one of the most popular tools in the attacker’s toolkit — and despite efforts to mitigate and eradicate its presence, it’s the unwanted gift that just keeps on giving.

In this post for SiliconANGLE, I describe the latest rounds of attacks and ways that you can try to stop them.

Red Cross: Lawyer Volunteers to Crunch the Numbers for the Red Cross

One of many amazing aspects about the volunteers of the American Red Cross is how diverse and unusual each volunteer’s background can be. That is certainly the case of Mrunmayee Pradhan, who began volunteering with the Missouri-Arkansas region three years ago. Timing is everything: she moved from India to the US in 2019, eventually settling in the Bentonville, Arkansas, area.

One of many amazing aspects about the volunteers of the American Red Cross is how diverse and unusual each volunteer’s background can be. That is certainly the case of Mrunmayee Pradhan, who began volunteering with the Missouri-Arkansas region three years ago. Timing is everything: she moved from India to the US in 2019, eventually settling in the Bentonville, Arkansas, area.

She began her career as a lawyer, eventually broadened her skillset by mastering data analysis tools from Google, Microsoft, and Tableau and began using them for large scale workforce management and tracking applications. That came in handy for the Red Cross, and you read more about her story here.

SiliconANGLE: Our national cybersecurity strategy is all over the place

Earlier this year, the Biden White House released its National Cybersecurity Strategy policy paper. Although it has some very positive goals, such as encouraging longer-term investments in cybersecurity, it falls short in several key areas. And compared with what is happening in Europe, once again the U.S. is falling behind and failing to get the job done.

The paper does a great job outlining the state of cybersecurity and its many challenges. What it doesn’t do is set out specific tasks or how to fund them. I analyze the situation for SiliconANGLE here.

SiliconANGLE: Is it time to deploy passkeys across the enterprise? Here’s what you need to know

It’s a great time to think more about passkeys, and not just because this Thursday is another World Password Day. Let’s look at where those 2022 passkey plans stand, and what companies will have to do to deploy them across their enterprises. Interest in the technology, also referred to as passwordless — a bit of a misnomer — has been growing since Google announced its support last fall and before that when Apple and Microsoft also came out in support last summer.

This post for SiliconANGLE discusses the progress made on these technologies, covers some of the remaining deployment issues, and reviews two sessions at the recent RSA Conference that can be useful for enterprise security managers.

The realities of ChatGPT as cyber threats (webcast)

I had an opportunity to be interviewed by Tony Bryant, of CyberUP, a cybersecurity non-profit training center, about the rise of ChatGPT and its relevance to cyber threats. This complemented a blog that I wrote earlier in the year on the topic, and certainly things are moving quickly with LLM-based AIs. The news this week is that IBM is replacing 7,800 staffers with various AI tools, making new ways of thinking about the future of upskilling GPT-related jobs more important. At the RSAC show last week, there was lots of booths that were focused on the topic, and more than 20 different conference sessions that ranged from danger ahead to how we can learn to love ChatGPT for various mundane security tasks, such as pen testing and vulnerability assessment. And of course news about how ChatGPT writes lots of insecure code, according to French infosec researchers, along with a new malware infostealer is out with a file named ChatGPT For Windows Setup 1.0.0.exe. Don’t download that one!

I had an opportunity to be interviewed by Tony Bryant, of CyberUP, a cybersecurity non-profit training center, about the rise of ChatGPT and its relevance to cyber threats. This complemented a blog that I wrote earlier in the year on the topic, and certainly things are moving quickly with LLM-based AIs. The news this week is that IBM is replacing 7,800 staffers with various AI tools, making new ways of thinking about the future of upskilling GPT-related jobs more important. At the RSAC show last week, there was lots of booths that were focused on the topic, and more than 20 different conference sessions that ranged from danger ahead to how we can learn to love ChatGPT for various mundane security tasks, such as pen testing and vulnerability assessment. And of course news about how ChatGPT writes lots of insecure code, according to French infosec researchers, along with a new malware infostealer is out with a file named ChatGPT For Windows Setup 1.0.0.exe. Don’t download that one!

There are still important questions you need to ask if you are thinking about deploying any chatbot app across your network, including how is your vendor using AI, which algorithms and training data are part of the model, how to build in any resilience or SDLC processes into the code, and what problem are you really trying to solve.