I have known Bruce Schneier for many years, and met him most recently just after he gave one of the keynotes at this year’s RSA show. The keynote extends his thoughts in his most recent book, A Hacker’s Mind, which he wrote last year and was published this past winter. (I reviewed some of his earlier works in a blog for Avast here.)

I have known Bruce Schneier for many years, and met him most recently just after he gave one of the keynotes at this year’s RSA show. The keynote extends his thoughts in his most recent book, A Hacker’s Mind, which he wrote last year and was published this past winter. (I reviewed some of his earlier works in a blog for Avast here.)

Even if you are new to Schneier, not interested in coding, and aren’t all that technical, you should read his book because he sets out how hacking works in our everyday lives.

He chronicles how hacks pervade our society. You will hear about the term Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich (how Google and Apple and others have hacked and thus avoided paying US taxes), the exploits of the Pudding Guy (the person who hacked American Airlines frequent flyer system by purchasing thousands of pudding cups to obtain elite status), or when the St. Louis Browns baseball team hacked things by hiring a 3’7″ batter back in 1951. There are less celebrated hacks, such as when investment firm Goldman Sachs owned a quarter of the total US aluminum supply back in the 2010’s to control its spot price. What was their hack? They moved it around several Chicago-area warehouses each day: the spot price depends on the time material is delivered. Clever, right?

Then there are numerous legislative and political hacks, such as the infamous voter literacy tests of the 1950s before the Civil Rights laws were passed. Schneier calls them “devilishly designed, selectively administered, and capriciously judged.”

“Our cognitive systems have also evolved over time,” he says, showing how they can be easily hacked, such as with agreements and contracts. This is because they can’t be made completely airtight, and we don’t really need that anyway: just the appearance of complete trust is usually enough for most purposes.

A good portion of his book concerns technology hacks, of course. He goes into details about how Facebook’s and You Tube’s algorithms are geared towards polarizing viewers, and the company not only knew this but specifically ignored the issue to optimize profits. The last chapters touch on AI issues, which he categorically says “will be used to hack us, and AI systems themselves will become the hackers” and find vulnerabilities in various social, economic and political systems. He makes a case for a hacking governance system that should be put in place — something which isn’t on the radar but should be.

“The more you can incorporate fundamental security principles into your systems design, the more secure you will be from hacking. Hacking is a balancing act. On the one hand, it is an engine of innovation. On the other, it subverts systems.” The trick is figuring out how to tip that balance.

I liked the conceit about this murder mystery novel by Hannah Mary McKinnon entitled

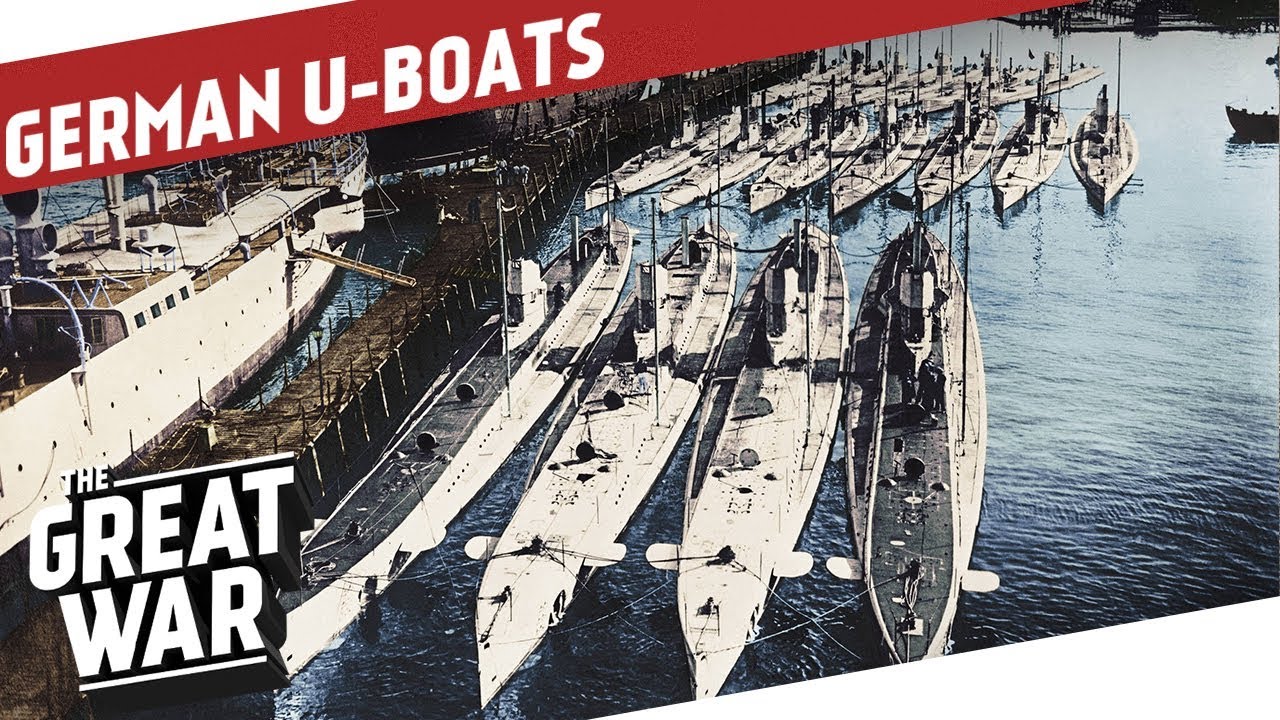

I liked the conceit about this murder mystery novel by Hannah Mary McKinnon entitled  All this chatter about ChatGPT and large language models interests me, but from a slightly different perspective. You see, back in those pre-PC days when I was in grad school at Stanford, I was building mathematical models as part of getting my degree in Operations Research. You might not be familiar with this degree, but basically was applying various mathematical techniques to solving real-world problems. OR got its beginnings trying to find German submarines and aircraft in WWII, and then got popular for all sorts of industrial and commercial applications post-war. As a newly minted math undergrad, the field had a lot of appeal, and at its heart was building the right model.

All this chatter about ChatGPT and large language models interests me, but from a slightly different perspective. You see, back in those pre-PC days when I was in grad school at Stanford, I was building mathematical models as part of getting my degree in Operations Research. You might not be familiar with this degree, but basically was applying various mathematical techniques to solving real-world problems. OR got its beginnings trying to find German submarines and aircraft in WWII, and then got popular for all sorts of industrial and commercial applications post-war. As a newly minted math undergrad, the field had a lot of appeal, and at its heart was building the right model.