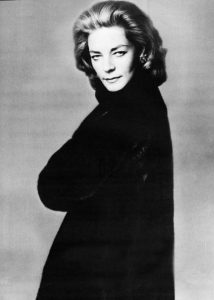

Those of you of a certain age might remember a print ad campaign for the Blackgama fur company that ran for many years, beginning in the 1960s with this image of Lauren Bacall wearing one of their mink coats.

I am riffing on this theme after visiting the National Cryptologic Museum outside the NSA offices in suburban Maryland this week. I remembered the ads because of my overall experience with the museum, and its relationship between its physical plant and the online and other publications that the historical arm of the NSA has produced.

As long-time readers recall, last summer I visited Bletchley Park in the UK. It was a great day spent at the complex and I learned a lot. Sadly, the NSA’s museum was a disappointment. And it made me realize that what makes a great museum when you first go to the actual building is part of what makes for a great online museum experience. Unfortunately, the NSA museum has neither.

Many of the world’s greatest museums have played catch-up when it comes to their websites. This is more than getting their catalogs digitized, then getting them redone with higher resolution or newer imaging technologies. It is more than organizing their collection for visitors, academics and other specialists that want to search them for their own research or just personal interests. It is also more than having something that is visually attractive to leverage the latest curatorial trends.

These great museums have also had to embrace technology in their actual buildings, something that I first wrote about for the NY Times when I visited the Abe Lincoln museum in Springfield, Ill. back in 2008. At that visit, I got to see first-hand a variety of things that are normally used in theatrical productions or rock concerts, such as spotlights, one-way mirrors and sophisticated sound systems to tell the story about Lincoln’s life and times. From this piece, I wrote for HPE’s blog about how the best code developers are learning to hone their craft and improve their user experience from these innovative museum designers. For example, augmenting the visuals with other sensory experiences, understanding the consequences of context switching when it comes to tell your story and so forth.

That is why the NSA museum stands out, but not in a good way. It is a subject that is near and dear to my heart, cryptology and its origins and use in the modern era. Check. It is located near the NSA, an interesting place in its own right. Check. It has plenty of classic stories about some key developments, going back to the Revolutionary War and how codes and encryption played a role in the birth of our country. Check. It has several Engima units on display, showing the evolution of the machine that you can actually touch. Check. It is dull as dishwater and has exhibits that looked like they were created back when the Apollo program was in its heyday. Big fail.

The best part of the museum wasn’t any of the exhibits but a tour that I happened upon led by a docent. Turns out he was a former Russian linguist that worked for the NSA for many years. His stories were great, and he answered all my questions with interesting personal insights (and correctly, I might add). I only wish he had a better physical plant to show his visitors.

For example, one exhibit is about how the Soviets bugged our buildings in Moscow. It begins with this object that is on display in the museum: it looks like a nicely crafted wooden replica of the US government seal. It was given to then U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman back in 1945 as a gift from Soviet children. It hung in the Ambassador’s residence for seven years, until a bug was found inside the carving. While what is shown is a replica, you can open a special hinge that was installed by the museum so you can see where the bug was located.

For example, one exhibit is about how the Soviets bugged our buildings in Moscow. It begins with this object that is on display in the museum: it looks like a nicely crafted wooden replica of the US government seal. It was given to then U.S. Ambassador Averell Harriman back in 1945 as a gift from Soviet children. It hung in the Ambassador’s residence for seven years, until a bug was found inside the carving. While what is shown is a replica, you can open a special hinge that was installed by the museum so you can see where the bug was located.

This story was a nice precursor to a major operation that took place in the 1970s called The Gunman Project. At that time, we found out the Soviets had increased their bugging program and put technology into 16 different IBM typewriters in our Moscow embassy offices to record the documents that were being prepared. I saw the Great Seal replica (and engaged with opening and closing it) at the museum, I took home a pamphlet about Gunman that I read avidly on the flight home. I tried to find an online copy of this document, I did find the text here. The document was nicely produced and I learned a lot from it. Now contrast that information with this link to another Gunman story, this one produced by two private Dutch crypto enthusiasts. It actually is a much better explanation, and even with the pictures included in the original NSA pamphlet, this latter piece is 1000% better and more engaging.

So if you are interested in the history of crypto, my suggestion is to forgo the actual visit. The NSA is working on building a new museum, but that could take years. In the meantime, read some of the supporting materials on their website or better yet, check out other entries at the online Crypto Museum. Second, if you are going to design a new museum, think of how the online and actual physical presence have to work together to build the best visitor experience.

Recently moved and reopened in DC to good reviews: https://www.spymuseum.org/

David,

I think you may like this article a bought “Decoding British ciphers used in the South, 1780-81”.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/06/decoding-british-ciphers-used-in-the-south-1780-81/