In the past week as massive demonstrations have taken place in Hong Kong we have also learned about how the Great Firewall of China operates. Thanks to a team lead by Harvard social scientist Gary King, it is an impressive collection of both manual and automated processes. The paper was published earlier this year in Science magazine here.

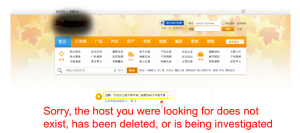

For those of you that aren’t familiar, China for years has been blocking a great deal of Internet traffic based on all sorts of criteria. Many of the world’s more popular social media sites, such as Facebook and Twitter, are completely unavailable inside the country. Newspapers that are freely read in the rest of the world are also blocked. King’s team conducted the first large-scale study of exactly what was censored and how it was done. They did so by creating thousands of social media accounts and posts and seeing what got blocked and when.

And more cleverly, they set up their own websites from within China and then paid to have them censored by the same firms that the government uses. This gave them access to the censor’s tech support lines, so they could engage them in a dialog to understand what was going on and be able to reverse engineer things. “We were even able to get their recommendations on how to conduct censorship on our own site in compliance with government standards,” they wrote.

And more cleverly, they set up their own websites from within China and then paid to have them censored by the same firms that the government uses. This gave them access to the censor’s tech support lines, so they could engage them in a dialog to understand what was going on and be able to reverse engineer things. “We were even able to get their recommendations on how to conduct censorship on our own site in compliance with government standards,” they wrote.

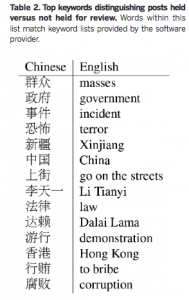

The study shows exactly how hard it is to censor Internet traffic, especially on the level that is seen in China where a half a billion social media posts are created every day. Automated keyword matching is flawed and requires a great deal of manual intervention. Posts that are critical of the Chinese government are routinely allowed but other posts that involve discussions of collective action (such as the recent Hong Kong demonstrations) are routinely blocked. Earlier research was less thorough and relied on more anecdotal information, not to mention was riskier since censors weren’t as willing to talk with outsiders about their processes and procedures.

Contrary to what has been written about the Great Firewall, social media site operators actually have a great deal of flexibility in how they function and what they allow online. And while the censors employ a wide variety of automated censorship routines across more than two-thirds of Chinese social media websites, these routines are for the most part ineffective and require thousands of people to monitor and censor the vast collection of content that is posted in China.

The team found that there was little censorship of posts about collective action events which occur outside mainland China, collective action events occurring solely online, social media posts containing critiques of top leaders, and posts about highly sensitive topics (such as Tibet) that do not occur during the actual collective action events themselves. Censors were more focused on the actual events that were taking place themselves and posts that related to organizing these “meetups” and the reactions to them.

The team found that there was little censorship of posts about collective action events which occur outside mainland China, collective action events occurring solely online, social media posts containing critiques of top leaders, and posts about highly sensitive topics (such as Tibet) that do not occur during the actual collective action events themselves. Censors were more focused on the actual events that were taking place themselves and posts that related to organizing these “meetups” and the reactions to them.

A few posts critical of the government were blocked, but not on the level that posts about the actual events were censored. “The censors don’t care about what you say, but about what you do,” said King. You can listen to King being interviewed by Ira Flatow on Science Friday here.

David,

My youngest son, also named David, has spent most of the last 8 years in East Asia: Japan, mainland China and now Kowloon. While on the mainland, he said that he was able to use various and sundry suberfuges to see the on-line NY Times, filtered out by the Great Firewall. Not sure exactly what he did with his Mac. The Great Firewall is not exactly Swiss cheese, but it is not impenetrable either… Ben Myers