It has been almost two months since the hacks surrounding SolarWinds’ Orion software were first revealed. We have learned a lot about the sloppy security practices at that company and its far-reaching consequences. Here are some of the takeaways for your own business security.

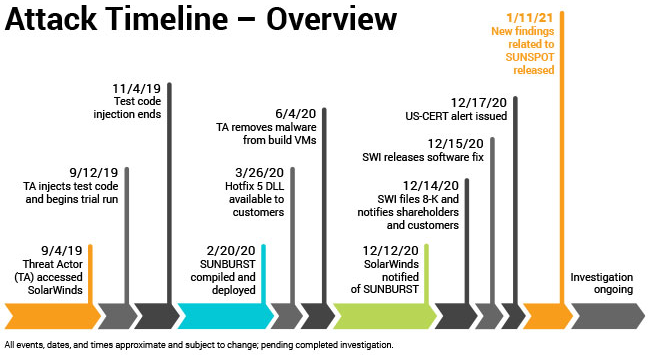

- SolarWinds was first breached in September 2019, yet evidence wasn’t found until last December, when the company issued two patches for its Orion network monitoring tool (the first attempt wasn’t completely successful). All of this is sadly typical for many breaches.

- The first major attack was called Sunspot, which then led to three further malware injections called Sunburst, Teardrop and Raindrop. These latter efforts were backdoor attacks that were used to penetrate more than 18,000 customer networks. Trustwave found additional vulnerabilities most recently, although these haven’t yet been exploited by any attackers.

- It wasn’t just Orion customers that were affected. CISA said last week that 30% of organizations breached did not have any Orion software installed. One of its customers was Fireeye and its own hacking tools were stolen as a result of the intrusion. Another security firm, Malwarebytes, isn’t an Orion customer but was hacked through similar means.

- The news about the attacks happened during a leadership transition. Sudhakar Ramakrishna became the CEO of SolarWinds at the beginning of this year and posted this update on what went wrong. My colleague Joe Panettieri lays out what should be his first priorities.

- If you are looking for a nice summary of best practice recommendations for SolarWinds by the consultants that are now working to fix their software development processes, check out this piece by CyberSecurity Dive.

- The attackers most certainly were Russian state-based, although there is new evidence that Chinese state-based attackers have also penetrated two US government agencies using similar malware.

Having mulled this one over for several weeks, the SolarWinds attack has some similarities to the world of hardware, in which companies lower down in the food chain produce counterfeit parts. The main similarity is that those lower in the food chain do not get subjected to appropriate scrutiny about their policies, practices, procedures and methods.