Last month I caught this news item about Microsoft building in a new command-line feature that is commonly called a network protocol sniffer. It is now freely available in Windows 10 and the post documents how to use it. Let’s talk about the evolution of the sniffer and how we come to this present-day development.

If we turn back the clock to the middle 1980s, there was a company called Network General that made the first Sniffer Network Analyzer. The company was founded by Len Shustek and Harry Saal. It went through a series of corporate acquisitions, spin outs and now its IP is owned by NetScout Systems.

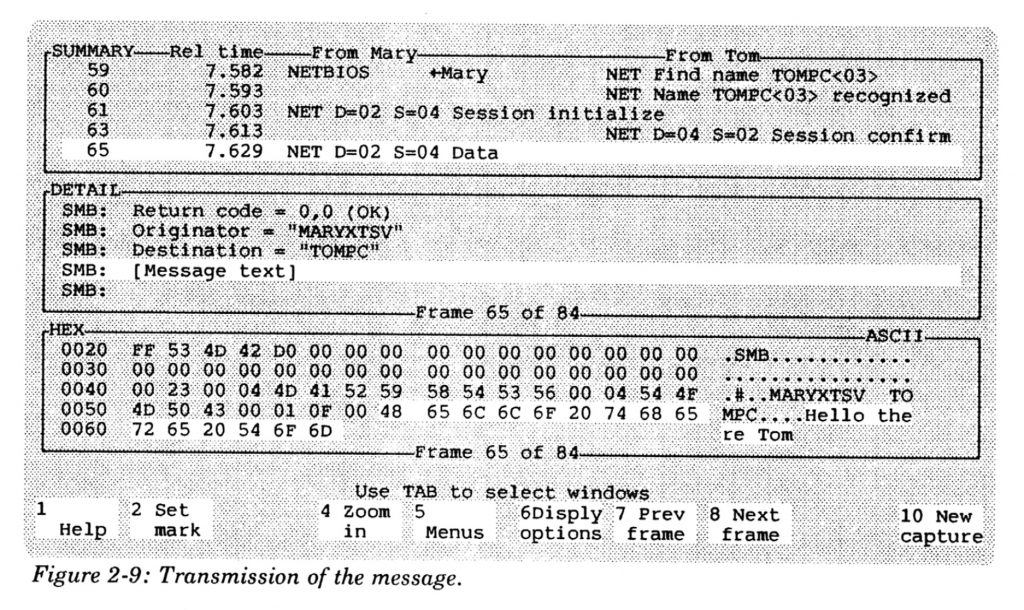

The Sniffer was the first machine you could put on a network and trace what packets were being transmitted. It was a custom-built luggable PC that was typical of the “portable” PCs of that era — it weighed about 30 pounds and had a tiny screen by today’s standards. It cost more than $10,000 to purchase, but then you needed to be trained how to use it. You would connect the Sniffer to your network, record the traffic into its hard drives, and then spend hours figuring out what was going on across your network. (Here is a typical information-dense display.) Decoding all the protocols and tracking down the individual endpoints and what they were doing was part art, part science, and a great deal of learning about the various different layers of the network and understanding how applications worked. Many times Sniffer analysts would find bugs in these applications, or in implementations of particular protocols, or fix thorny network configuration issues.

The Sniffer was the first machine you could put on a network and trace what packets were being transmitted. It was a custom-built luggable PC that was typical of the “portable” PCs of that era — it weighed about 30 pounds and had a tiny screen by today’s standards. It cost more than $10,000 to purchase, but then you needed to be trained how to use it. You would connect the Sniffer to your network, record the traffic into its hard drives, and then spend hours figuring out what was going on across your network. (Here is a typical information-dense display.) Decoding all the protocols and tracking down the individual endpoints and what they were doing was part art, part science, and a great deal of learning about the various different layers of the network and understanding how applications worked. Many times Sniffer analysts would find bugs in these applications, or in implementations of particular protocols, or fix thorny network configuration issues.

My first brush with the Sniffer was in 1988 when I was an editor at PC Week (now eWeek). Barry Gerber and I were working on one of the first “network topology shootouts” where we pit a network of PCs running on three different wiring schemes against each other. In addition to Ethernet there was also Token Ring (an IBM standard) and Arcnet. We took over one of the networked classrooms at UCLA during spring break and hooked everything up to a Novell network file server that ran the tests. We needed a Sniffer because we had to ensure that we were doing the tests properly and make sure it was a fair contest.

Ethernet ended up wining the shootout, but we did find implementation bugs in the Novell Token Ring drivers. Eventually Ethernet became ubiquitous and today you use it every time you bring up a Wifi connection on your laptop or phone.

Since the early Sniffer days, protocol analysis has moved into the open source realm and WireShark is now the standard application software tool used. It doesn’t require a great deal of training, although you still need to know your seven layer network protocol model. I have used Sniffers on several occasions doing product reviews, and one time helped to debug a particularly thorny network problem for an office of the American Red Cross. We tracked the problem to a faulty network card in one user’s PC which was just flaky enough to operate correctly most of the time.

Today, sniffers can be found in a number of hacking tools, as this article in ComputerWorld documents. And now inside of WIndows 10 itself. How about that?

I asked Saal what he thought about the Microsoft Windows sniffer feature. “It is now almost 35 years since its creation. Seeing that some similar functionality is now hard wired into the guts of Windows 10 is amusing. Microsoft makes a first class Windows GUI tool, NetMon, available for free and of course there is WireShark. Why Microsoft would invest design, programming and test resources into creating a text-based command line tool is beyond me. What unfilled need does it satisfy? Regardless, more is better, so I say good luck to Redmond and the future of Windows.”

David

Look closely at the picture, top line. It is Wireshark! Look further down, and see how the packet being analyzed is HTTP 1.1. Did you say 1988? Oh, ok, this is not from the luggable that you mentioned.

The amazing thing that strikes me is that most of the web is still on HTTP1.1 (version 2 is making inroads, but still is in fewer than 50% of web servers), and If I were to reach for a protocol analyser it would still be Wireshark. Remember when it was called EtherFind?

cheers — Rick

This reply refers to an earlier image that had a protocol capture of Wireshark. I thought it might be better to use an actual Sniffer screenshot, which you can see here. Thanks Rick for the explanation.

My networking life started with ethereal….it was open source, fast & light, in 2000.

I remember the Network General sniffer! When we built the first Part 15 unlicensed 915 MHz 128 kbps wireless LAN in 1988 on top of the AppleTalk protocols, which of course were totally unencrypted and unprotected, some people worried that “spies” could sit in your parking lot with one of these sniffers and hoover down all the traffic you sent to your printer. I believe our response was “who cares, we’ll worry about that later.” 😊

Saal’s Sniffer, wasn’t the first capability or even the first product. Just the first successful product…

I’m not sure who did the actual first sniffing.

By way of example: I went to Ungermann-Bass in 1986 and fairly quickly was tasked with our putting TCP/IP onto their ‘intelligent’ networking card for PCs. It had an Intel 186 on it, for offloading from the PC’s Intel 286. I happened to come across an existing bit of code in the company that did XNS sniffing, including symbolically interpreted display. UB had adapted XNS for its original networking protocol, as had other companies. This had been just before TCP/IP was ready for productization.) I adapted the interpretive code to also display TCP/IP, since I was never very good at reading octal or hex protocol displays…

For the second installation of our new TCP/IP PC product, I brought a PC to display the TCP/IP traffic symbolically, so the customer could see what went over the wire as we demonstrated the PC product they’d bought. The customer pretty much took for granted the operation of the product, but they were fascinated by the protocol display. Sometimes single-data research is useful. He was a network admin with no insight into his network’s operation and the protocol display changed that.

I went back to UB and suggested we productize. The marketing guys said they would not know how to sell it. When I switched to The Wollongong Group in 1987, we built a fresh sniffer product but its marketing group also could not figure out how to sell it.

Somewhere during this latter round, Saal started Network General. I remembering being quite upset at our/my missed opportunity when he pass $1M per month of revenue…