What do the authors Beatrix Potter, Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Allan Poe and the British composer Edward Elgar have in common with the Zodiac killer, Mary Queen of Scots, and an enigmatic map left in the 1880s by Virginian buffalo hunter named Thomas Beale? They all were fascinated by communicating by codes. And if you are too and want to learn how to break them yourself, you should pick up the latest expanded edition of Codebreaking by Elonka Dunin and Klaus Schmeh that is expected in September. Their book takes you through the codes used by these historical luminaries, some of them (such as one of the Zodiac messages or the mysterious Voynich manuscript) have never been broken. And there are plenty that have been solved, such as a single telegram that was decrypted and brought the US to enter WWI.

What do the authors Beatrix Potter, Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Allan Poe and the British composer Edward Elgar have in common with the Zodiac killer, Mary Queen of Scots, and an enigmatic map left in the 1880s by Virginian buffalo hunter named Thomas Beale? They all were fascinated by communicating by codes. And if you are too and want to learn how to break them yourself, you should pick up the latest expanded edition of Codebreaking by Elonka Dunin and Klaus Schmeh that is expected in September. Their book takes you through the codes used by these historical luminaries, some of them (such as one of the Zodiac messages or the mysterious Voynich manuscript) have never been broken. And there are plenty that have been solved, such as a single telegram that was decrypted and brought the US to enter WWI.

The book’s focus is on using your wits and pencil and paper to solve the puzzles for the most part, although the authors aren’t computer-adverse: they use the old fashioned methods to help develop the reader’s skills and to pay attention to the frequency distribution of the coded letters and symbols used in the messages, among other tricks of the trade that they describe in detail.

The book’s focus is on using your wits and pencil and paper to solve the puzzles for the most part, although the authors aren’t computer-adverse: they use the old fashioned methods to help develop the reader’s skills and to pay attention to the frequency distribution of the coded letters and symbols used in the messages, among other tricks of the trade that they describe in detail.

Dunin may be a familiar name to you: Years ago, I had an opportunity to meet her in person when she spoke at a conference in St. Louis. She is a very impressive person, and carries a deep history and understanding of the genre. She is tightly associated with an encoded sculpture that sits on the grounds of the CIA campus, which still contains an unsolved portion after decades of tries by the best and brightest cryptographers. Her co-author has written numerous books as well and maintains the Encrypted Books List that is a useful companion to learn more about the topic, along with providing numerous illustrations that begin each of the book’s chapters.

This book is nearly 500 pages, and chock full of illustrations of the original coded messages as well as other helpful materials that show how codebreakers figure things out. Because of this, I would recommend buying the printed copy rather than an ebook. Each chapter is devoted to particular techniques, such as “hill climbing” where you proceed to decode a word at a time and continually measure your progress. This technique has proven very successful at breaking historical codes and uses computer algorithms.

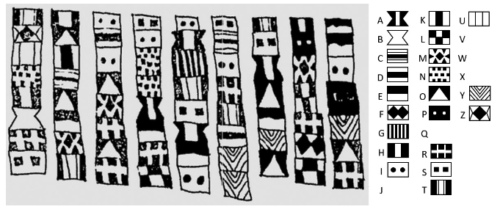

The authors were motivated to update their first edition because so many major codes have been cracked over the past few years — including the aforementioned one by Mary Queen of Scots. The stories of these escapades is what makes this book entertaining as well as informative, and you realize that codebreaking is a team sport. The encoded message above, by the way, is one of the many Zodiac copycats who wrote messages to the police pretending to be the actual killer. See if you can work out what it says.

Thanks for publishing the first review of our book, which will be published in September.

Klaus Schmeh

I marked this as unread until I could share it with my 11yo son, Hank. He loves math and science and his favorite thing is Space Camp. I’ve been trying to convince him to switch from Aviation to Cyber Camp, and he was so interested in the topic of codebreaking that I may have convinced him!

Thanks for your ever-fascinating blog, David!