Think of it as both a reference guide as well as a collection of carefully curated tools that can help infosec researchers get smarter about understanding potential threats (such as YARA, Sigma, and log analyzers) and the ways in which criminals use them to penetrate your networks.

For threat intel beginners, he describes the processes involved in breach investigation, how you gather information and vet it, and weigh various competing hypotheses to come up with what actually happened across your computing infrastructure. He then builds on these basics with lots of useful and practical methods, tools, and techniques.

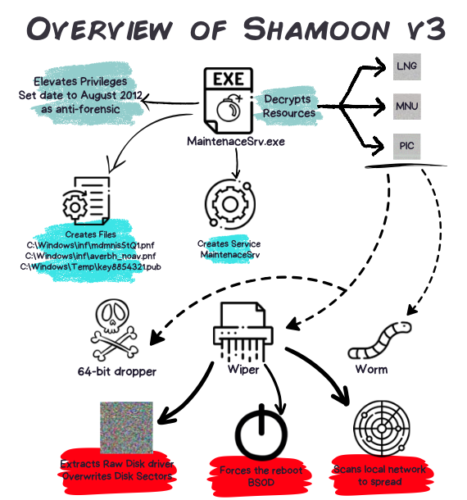

One chapter goes into detail about the more notorious hacks of the past, including Stuxnet, the 2014 Sony hack, and WannaCry. There are timelines of what happened when, graphical representations of how the attack happened (such as the overview of the Shamoon atttack shown here),  mapping the attack to the diamond model (focusing on adversaries, infrastructure, capabilities, and victims) and a summary of the MITRE ATT&CK tactics. That is a lot of specific information that is presented in a easily readable manner. I have been writing about cybersecurity for many years and haven’t seen such a cogent collection in one place of these more infamous attacks.

mapping the attack to the diamond model (focusing on adversaries, infrastructure, capabilities, and victims) and a summary of the MITRE ATT&CK tactics. That is a lot of specific information that is presented in a easily readable manner. I have been writing about cybersecurity for many years and haven’t seen such a cogent collection in one place of these more infamous attacks.

Roccia also does a deeper dive into his own investigation of NotPetya for two weeks during the summer of 2017. “It was the first time in my career that I fully realized the wide-ranging impact of a cyberattack — not only on data but also on people,” he wrote.

The book’s appendix contains a long annotated list of various open source tools useful for threat intel analysts. I highly recommend the book if you are interested in learning more about the subject and are looking for a very practical guide that you can use in your own investigations.