As some of you who follow my work know, I have had a long history of using and complaining about email encryption programs, ever since working with Marshall Rose on our breakthrough 1998 book on enterprise Internet messaging. Rose was one of the key innovators of the Internet email protocols that we still use today, and a wonderful co-author.

As some of you who follow my work know, I have had a long history of using and complaining about email encryption programs, ever since working with Marshall Rose on our breakthrough 1998 book on enterprise Internet messaging. Rose was one of the key innovators of the Internet email protocols that we still use today, and a wonderful co-author.

Since those dark days, email encryption has certainly gotten better, as I wrote this past summer when I tested a bunch of products for Network World. But is it good enough to pass muster with academia? Not yet, at least on the level of the average undergraduate recruited for a recent academic paper in the “Johnny Can’t Encrypt” research series.

These papers began in 1999, when a Berkeley computer science team published the first study based on trying to use PGPv 5. The research design is very straightforward: pairs of students were asked to send and decrypt messages back and forth under observation. Few of the teams were able to complete the task in under 90 minutes. In 2006, another team at Carnegie Mellon tried again, this time using an Outlook Express plug-in with PGP v9. They had better software but less time to complete their tasks, and most eventually still failed.

And last month, a team at BYU tried again, this time using Gmail and Mailvelope. They gave their teams 30 minutes, with only one out of ten being able to get the job done. The most common mistake was encrypting a message with the sender’s public key, a rookie mistake. There were other user experience issues with the Mailvelope browser plug-in, and some students were clearly very frustrated and vented their low opinions of Mailvelope to the researchers.

PGP has been around a long time, since 1991 when it was created by Phil Zimmermann. Phil is still active in the field, having worked on a newer series of “Silent” email products. I spoke to another Phil involved with PGP, Phil Dunkelberger, who ran PGP and now is running a major effort to spread encryption to the world, Nok Nok Labs. He told met that their results “weren’t surprising, given that they were testing technology that has its roots in the 1980s. The problem is balancing ease of use with key management, and products need to focus on solving both issues if they are going to succeed in the marketplace.” While not singling out Mailvelope specifically, the history of email encryption is filled with other efforts that have failed because of these fundamental flaws.

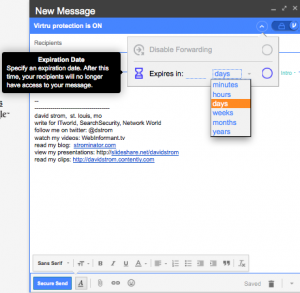

I will admit that PGP, in whatever vintage (the current version that I have used is v10) isn’t the easiest software to use. Since it was sold to Symantec, it has fallen on disuse and there are a lot of other tools out there that are better alternatives. I was a bit surprised at all vitriol directed at Mailvelope by the BYU students: I gave it a brief spin and it seemed to work reasonably well. Perhaps I would have chosen Virtru (pictured above) or some other tool.

Thanks to Ed Snowden, we are more sensitive to how we manage our encryption key infrastructure, and also understand the difference between encrypting the actual message data – the message body and attachments – versus the metadata contained in each message, such as subject lines and recipient names. As I wrote this summer, “encryption has finally come of age, and is appealing to those beyond the tinfoil-hat set.”

Certainly, we still have a long way to go before encryption will become the default mechanism for email communications. But today’s tools are certainly good enough for general use, even by the average undergraduate. Now we have to move on to using encrypted messaging apps.

Enigmail for Thunderbird is pretty nice. A checkbox is all you need to set to sign or encrypt. It figures it all out and just does it. Incoming messages are simply verified or decrypted with no extra steps.

The problem is key management and trust assignments which people don’t want to be bothered with. They give up far too quickly.

Thank heaven X.509 and friends are on their deathbed (except for webserver SSL/TLS certs, ugh).

This article was written several years ago. I more recent (and more basic) guide on encrypted emails can be found here:

https://pixelprivacy.com/resources/encrypted-messaging/